A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads derive from the medieval French chanson balladée or ballade, which were originally "dance songs". Ballads were particularly characteristic of the popular poetry and song of Britain and Ireland from the Late Middle Ages until the 19th century. They were widely used across Europe, and later in Australia, North Africa, North America and South America.

Poetry, also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, a prosaic ostensible meaning. A poem is a literary composition, written by a poet, using this principle.

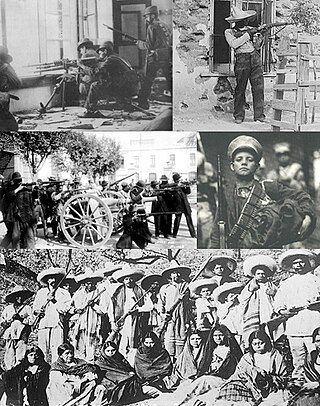

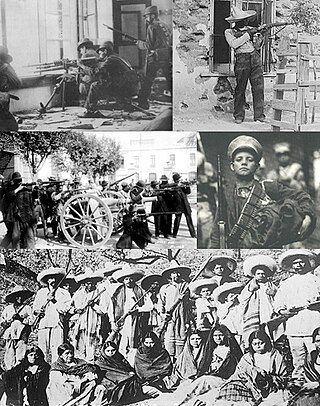

The Mexican Revolution was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history" and resulted in the destruction of the Federal Army, its replacement by a revolutionary army, and the transformation of Mexican culture and government. The northern Constitutionalist faction prevailed on the battlefield and drafted the present-day Constitution of Mexico, which aimed to create a strong central government. Revolutionary generals held power from 1920 to 1940. The revolutionary conflict was primarily a civil war, but foreign powers, having important economic and strategic interests in Mexico, figured in the outcome of Mexico's power struggles; the U.S. involvement was particularly high. The conflict led to the deaths of around one million people, mostly noncombatants.

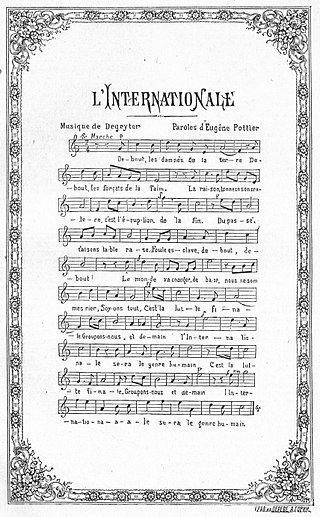

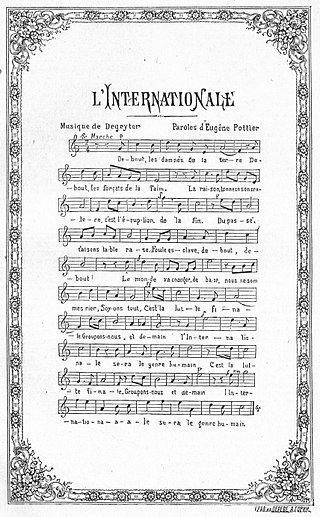

"The Internationale" is an international anthem that has been adopted as the anthem of various anarchist, communist, socialist, democratic socialist, and social democratic movements. It has been a standard of the socialist movement since the late nineteenth century, when the Second International adopted it as its official anthem. The title arises from the "First International", an alliance of workers which held a congress in 1864. The author of the anthem's lyrics, Eugène Pottier, an anarchist, attended this congress. Pottier's text was later set to an original melody composed by Pierre De Geyter, a Marxist.

Ranchera or canción ranchera is a genre of traditional music of Mexico. It dates to before the years of the Mexican Revolution. Rancheras today are played in the vast majority of regional Mexican music styles. Drawing on rural traditional folk music, the ranchera developed as a symbol of a new national consciousness in reaction to the aristocratic tastes of the period.

The valona is a popular narrative song- and poetry-form of the Mexican state of Michoacán. Its main characteristics are a bitter sense of humor, bawdy content, and social concerns. The lyrics of a Valona are composed as groupings of ten-line strophes, each line made up of eight syllables; musically, all valonas are sung to just a single tune, with an instrumental refrain after each strophe, which can vary.

The corrido is a famous narrative metrical tale and poetry that forms a ballad. The songs are often about oppression, history, daily life for criminals, the vaquero lifestyle, and other socially relevant topics. Corridos were widely popular during the Mexican Revolution and in the Southwestern American frontier as it was also a part of the development of Tejano and New Mexico music, which later influenced Western music.

A narcocorrido is a subgenre of the Regional Mexican corrido genre, from which several other genres have evolved. This type of music is heard and produced on both sides of the Mexico–US border. It uses a danceable, polka, waltz or mazurka rhythmic base.

The villancico or vilancete was a common poetic and musical form of the Iberian Peninsula and Latin America popular from the late 15th to 18th centuries. Important composers of villancicos were Juan del Encina, Pedro de Escobar, Francisco Guerrero, Manuel de Zumaya, Juana Inés de la Cruz, Gaspar Fernandes, and Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla.

La Cucaracha is a nationally syndicated daily comic strip by Lalo Alcaraz. First published in the LA Weekly in 1992, La Cucaracha's satirical themes reflect U.S./Mexican, and Latino culture and politics. Lalo's characters are symbolic of Latino culture in the United States, particularly from Southern California, where Alcaraz is from. Recurring characters include Eddie, Cuco, and Vero.

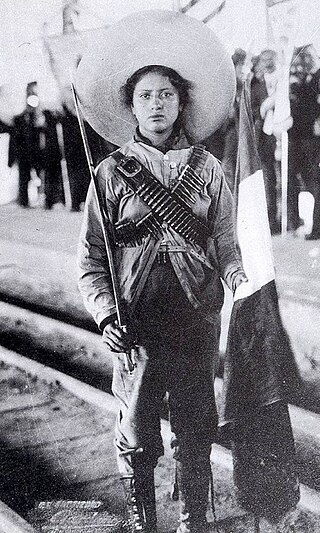

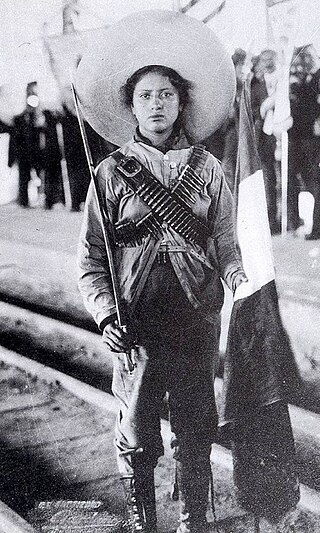

"La Adelita" is one of the most famous corridos of the Mexican Revolution. Over the years, it has had many adaptations. The ballad was inspired by a Chihuahuense woman who joined the Maderista movement in the early stages of the revolution and fell in love with Madero. She became a popular icon and a symbol of the role of women in the Mexican Revolution. The figure of the adelita gradually became synonymous with the term soldadera, the woman in a military-support role, who became a vital force in the revolutionary efforts through provisioning, espionage, and other activities in the battles against Mexican federal government forces.

Soldaderas, often called Adelitas, were women in the military who participated in the conflict of the Mexican Revolution, ranging from commanding officers to combatants to camp followers. "In many respects, the Mexican revolution was not only a men's but a women's revolution." Although some revolutionary women achieved officer status, coronelas, "there are no reports of a woman achieving the rank of general." Since revolutionary armies did not have formal ranks, some women officers were called generala or coronela, even though they commanded relatively few men. A number of women took male identities, dressing as men, and being called by the male version of their given name, among them Ángel Jiménez and Amelio Robles Ávila.

José Joaquín Eugenio Fernández de Lizardi Gutiérrez, Mexican writer and political journalist, best known as the author of El Periquillo Sarniento (1816), translated as The Mangy Parrot in English, reputed to be the first novel written in Latin America.

This is a glossary of poetry terms.

"Cielito Lindo" is a Mexican folk song or copla popularized in 1882 by Mexican author Quirino Mendoza y Cortés. It is roughly translated as "Lovely Sweet One". Although the word cielo means "sky" or "heaven", it is also a term of endearment comparable to "sweetheart" or "honey". Cielito, the diminutive, can be translated as "sweetie"; lindo means "cute", "lovely" or "pretty". The song is commonly known by words from the refrain, "Canta y no llores", or simply as the "Ay, Ay, Ay, Ay song".

Adelita or Adelitas may refer to:

The Soldiers of Pancho Villa is a 1959 Mexican epic historical drama film co-written, produced, and directed by Ismael Rodríguez, inspired by the popular Mexican Revolution corrido "La Cucaracha". It stars María Félix and Dolores del Río in the lead roles, and features Emilio Fernández, Antonio Aguilar, Flor Silvestre, and Pedro Armendáriz in supporting roles.

"Las Mañanitas"Spanish pronunciation:[lasmaɲaˈnitas] is a traditional Mexican birthday song written by Mexican composer Alfonso Esparza Oteo. It is popular in Mexico, usually sung early in the morning to awaken the birthday person, and especially as part of the custom of serenading women. A famous rendition of "Las Mañanitas" is sung by Pedro Infante to "Chachita" in the movie Nosotros los pobres. It is also sung in English in The Leopard Man (1943).

Adela Velarde Pérez was a Mexican activist who fought in the Mexican Revolution.

Valentín de la Sierra is a corrido commemorating the death of Valentín Ávila Ramírez, a Cristero rebel who was killed in 1926 by the Mexican Army. The song is attributed to Chimano Noriega and Elidio Pacheco. It has been recorded by a variety of artists, including Vicente Fernández and Ana Gabriel.