A music video is a video that integrates a song or an album with imagery that is produced for promotional or musical artistic purposes. Modern music videos are primarily made and used as a music marketing device intended to promote the sale of music recordings. These videos are typically shown on music television and on streaming video sites like YouTube, or more rarely shown theatrically. They can be commercially issued on home video, either as video albums or video singles. The format has been described by various terms including "illustrated song", "filmed insert", "promotional (promo) film", "promotional clip", "promotional video", "song video", "song clip", "film clip", "video clip", or simply "video".

An American Werewolf in London is a 1981 comedy horror film written and directed by John Landis. An international co-production of the United Kingdom and the United States, the film stars David Naughton, Jenny Agutter, Griffin Dunne and John Woodvine. The title is a cross between An American in Paris and Werewolf of London. The film's plot follows two American backpackers, David and Jack, who are attacked by a werewolf while travelling in England, causing David to become a werewolf under the next full moon.

Rob Zombie is an American singer, songwriter, record producer, filmmaker, and actor. His music and lyrics are notable for their horror and sci-fi themes, and his live shows have been praised for their elaborate shock rock theatricality. He has sold an estimated 15 million albums worldwide.

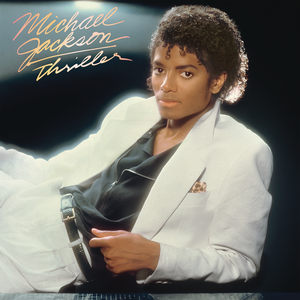

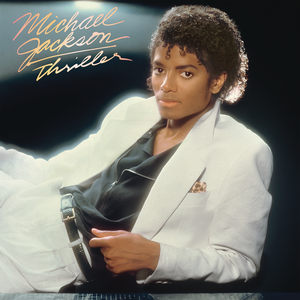

Thriller is the sixth studio album by the American singer and songwriter Michael Jackson, released on November 29, 1982, by Epic Records. It was produced by Quincy Jones, who had previously worked with Jackson on his 1979 album Off the Wall and who would later produce his 1987 album Bad. Jackson wanted to create an album where "every song was a killer". With the ongoing backlash against disco music at the time, he moved in a new musical direction, resulting in a mix of pop, post-disco, rock, funk, synth-pop, and R&B sounds. Thriller foreshadows the contradictory themes of Jackson's personal life, as he began using a motif of paranoia and darker themes. Paul McCartney appears on "The Girl Is Mine", the first credited appearance of a featured artist on a Michael Jackson album. Recording took place from April to November 1982 at Westlake Recording Studios in Los Angeles, California, with a budget of $750,000.

John David Landis is an American filmmaker and actor. He is best known for the comedy films that he has directed – such as The Kentucky Fried Movie (1977), National Lampoon's Animal House (1978), The Blues Brothers (1980), An American Werewolf in London (1981), Trading Places (1983), Three Amigos (1986), Coming to America (1988) and Beverly Hills Cop III (1994), and for directing Michael Jackson's music videos for "Thriller" (1983) and "Black or White" (1991).

"Thriller" is a song by the American singer-songwriter Michael Jackson. It was released by Epic Records in November 1983 in the UK and on January 23, 1984, in the US, as the seventh and final single from his sixth studio album, Thriller.

Sheri Moon Zombie is an American actress, model, dancer and fashion designer.

"Black or White" is a song by American singer Michael Jackson, released by Epic Records on November 11, 1991, as the first single from his eighth studio album, Dangerous (1991). Jackson wrote, composed, and produced it with Bill Bottrell. Epic Records described it as "a rock 'n' roll dance song about racial harmony".

The Dangerous World Tour was the second world concert tour by American singer Michael Jackson and was staged to promote his eighth studio album Dangerous. The tour was sponsored by Pepsi-Cola. All profits were donated to various charities including Jackson's own "Heal the World Foundation". It began in Munich, Germany, on June 27, 1992, and concluded in Mexico City, Mexico, on November 11, 1993, playing 69 concerts in Europe, Asia and Latin America. Jackson performed in stadiums across the world with all being sold out in countries in Asia, Latin America, and Europe. At the tour's end, it grossed over $100 million and was attended by 3,500,000 people.

Richard Alan Baker, known professionally as Rick Baker, is an American retired special make-up effects creator and actor. He is mostly known for his creature designs and effects. Baker has won the Academy Award for Best Makeup a record seven times from a record eleven nominations, beginning when he won the inaugural award for the 1981 horror comedy film An American Werewolf in London.

The Thriller jacket is the red jacket worn by Michael Jackson in the music video for his 1983 hit "Thriller". Designed by Deborah Nadoolman Landis, the candy-apple-red jacket featured black stripes and raised shoulders forming an inverted triangle. The jacket became the "hottest outerwear fad of the mid-1980s" and was widely emulated. Because counterfeit copies of the jacket could sell at over $500, in 1984 Jackson filed a lawsuit in New York City to prevent unauthorized copies of the jacket and his other merchandise.

The Midnight Hour is a 1985 American made-for-television comedy horror film directed by Jack Bender and starring Shari Belafonte-Harper, LeVar Burton, Peter DeLuise, and Dedee Pfeiffer. Its plot focuses on a small New England town that becomes overrun with zombies, witches, vampires, and all the other demons of hell after a group of teenagers unlocks a centuries-old curse on Halloween.

Michael Joseph Jackson was an American singer, songwriter, dancer, and philanthropist. Known as the "King of Pop", he is widely regarded as one of the most significant cultural figures of the 20th century. During his four-decade career, his contributions to music, dance, and fashion, along with his publicized personal life, made him a global figure in popular culture. Jackson influenced artists across many music genres. Through stage and video performances, he popularized complicated street dance moves such as the moonwalk, which he named, as well as the robot.

American singer Michael Jackson (1958–2009) debuted on the professional music scene at age five as a member of the American family music group The Jackson 5 and began a solo career in 1971 while still part of the group. Jackson promoted seven of his solo albums with music videos or, as he would refer to them, "short films". Some of them drew criticism for their violent and sexual elements while others were lauded by critics and awarded Guinness World Records for their length, success, and cost.

"Beat It" is a song by American singer-songwriter Michael Jackson from his sixth studio album, Thriller (1982). It was written and composed by Jackson and produced by Quincy Jones and co-produced by Jackson. Jones encouraged Jackson to include a rock song on the album. Jackson later said: "I wanted to write a song, the type of song that I would buy if I were to buy a rock song... and I wanted the children to really enjoy it—the school children as well as the college students." It includes a guitar solo by Eddie Van Halen.

Travis Payne is an American choreographer, director, and producer. He was the choreographer for Michael Jackson's This Is It until Jackson's death. Payne also served as the associate producer for This Is It and along with the director, Kenny Ortega, was extensively and intimately involved in the making of the film. To date, This Is It worldwide gross revenue totaled $261.3 million during its theatrical run, making it the highest-grossing documentary or concert movie of all time.

Thrill the World is an annual international dance event and world record breaking attempt, in which participants simultaneously emulate the zombie dance seen in the music video of Michael Jackson's "Thriller". The dancers perform in unison at locations throughout the world, and can range from kids and pre-teens to the elderly. Ines Markeljevic created the event "Thrill Toronto" where she taught a group of 62 zombies the dance in a mere couple of hours and they set the first Guinness World Records for Largest Thriller Dance in one location, at a community hall in Canada. Ines Markeljevic is dance instructor and entrepreneur from Toronto, Canada, whose personal mission is to unite the world through dance.

Michael Jackson's This Is It is a 2009 American documentary film about Michael Jackson's preparation for This Is it, a series of concerts that were cancelled due to his death in 2009. Named for the concert residency of the same name, the film includes additional behind the scenes footage, including dancer auditions and costume design. The film's director, Kenny Ortega, confirmed that none of the footage was originally intended for release, but after Jackson's death, it was agreed that the film would be made. The footage was filmed in California at the Staples Center and The Forum.

American singer-songwriter Michael Jackson (1958–2009) is regarded as one of the most significant cultural figures of the 20th and 21st century and one of the most successful and influential entertainers of all time. Often referred as the "King of Pop", his achievements helped to complete the desegregation of popular music in the United States and introduced an era of multiculturalism and integration that future generations of artists followed. His influence extended to inspiring fashion trends and raising awareness for social causes around the world.

Michael Jackson's Halloween is a one-hour animated television special that premiered on CBS on October 27, 2017. It was produced by Splash Entertainment.