An earth shelter, also called an earth house, earth-bermed house, earth-sheltered house, earth-covered house, or underground house, is a structure with earth (soil) against the walls and/or on the roof, or that is entirely buried underground.

A courtyard or court is a circumscribed area, often surrounded by a building or complex, that is open to the sky.

Vernacular architecture is building done outside any academic tradition, and without professional guidance. It is not a particular architectural movement or style, but rather a broad category, encompassing a wide range and variety of building types, with differing methods of construction, from around the world, both historical and extant and classical and modern. Vernacular architecture constitutes 95% of the world's built environment, as estimated in 1995 by Amos Rapoport, as measured against the small percentage of new buildings every year designed by architects and built by engineers.

A Hakka walled village is a large multi-family communal living structure that is designed to be easily defensible. This building style is unique to the Hakka people found in southern China. Walled villages are typically designed for defensive purposes and consist of one entrance and no windows at the ground level.

Chinese architecture is the embodiment of an architectural style that has developed over millennia in China and has influenced architecture throughout East Asia. Since its emergence during the early ancient era, the structural principles of its architecture have remained largely unchanged. The main changes involved diverse decorative details. Starting with the Tang dynasty, Chinese architecture has had a major influence on the architectural styles of neighbouring East Asian countries such as Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and Mongolia in addition to minor influences on the architecture of Southeast and South Asia including the countries of Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and the Philippines.

A dugout or dug-out, also known as a pit-house or earth lodge, is a shelter for humans or domesticated animals and livestock based on a hole or depression dug into the ground. Dugouts can be fully recessed into the earth, with a flat roof covered by ground, or dug into a hillside. They can also be semi-recessed, with a constructed wood or sod roof standing out. These structures are one of the most ancient types of human housing known to archaeologists, and the same methods have evolved into modern "earth shelter" technology.

The kang is a traditional heated platform, 2 metres or more long, used for general living, working, entertaining and sleeping in the northern part of China, where the winter climate is cold. It is made of bricks or other forms of fired clay and more recently of concrete in some locations. The word kang means "to dry".

A siheyuan is a type of dwelling that was commonly found throughout China, most famously in Beijing and rural Shanxi. Throughout Chinese history, the siheyuan composition was the basic pattern used for residences, palaces, temples, monasteries, family businesses, and government offices. In ancient times, a spacious siheyuan would be occupied by a single, usually large and extended family, signifying wealth and prosperity. Today, remaining siheyuan are often still used as subdivided housing complexes, although many lack modern amenities.

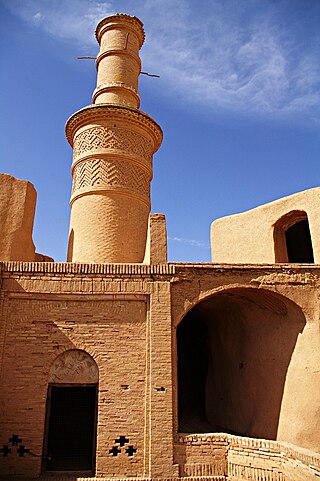

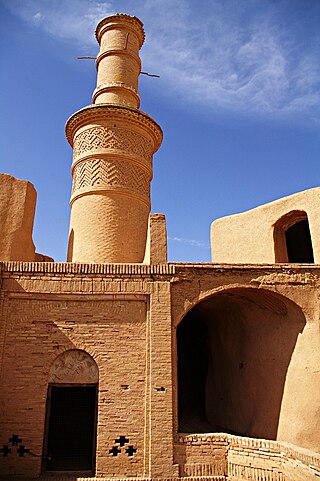

A yaodong is a particular form of earth shelter dwelling common in the Loess Plateau in China's north. They are generally carved out of a hillside or excavated horizontally from a central "sunken courtyard".

An earth structure is a building or other structure made largely from soil. Since soil is a widely available material, it has been used in construction since prehistory. It may be combined with other materials, compressed and/or baked to add strength.

The Fujiantulou are Chinese rural dwellings unique to the Hakka in the mountainous areas in southeastern Fujian, China. They were mostly built between the 12th and the 20th centuries.

Architecture of Tibet contains influences from neighboring regions but has many unique features brought about by its adaptation to the cold, generally arid, high-altitude climate of the Tibetan plateau. Buildings are generally made from locally available construction materials, and are often embellished with symbols of Tibetan Buddhism. For example, private homes often have Buddhist prayer flags flying from the rooftop.

The architecture of Madagascar is unique in Africa, bearing strong resemblance to the construction norms and methods of Southern Borneo from which the earliest inhabitants of Madagascar are believed to have immigrated. Throughout Madagascar, the Kalimantan region of Borneo and Oceania, most traditional houses follow a rectangular rather than round form, and feature a steeply sloped, peaked roof supported by a central pillar.

Rumah adat are traditional houses built in any of the vernacular architecture styles of Indonesia, collectively belonging to the Austronesian architecture. The traditional houses and settlements of the several hundreds ethnic groups of Indonesia are extremely varied and all have their own specific history. It is the Indonesian variants of the whole Austronesian architecture found all over places where Austronesian people inhabited from the Pacific to Madagascar each having their own history, culture and style.

Stilts are poles, posts or pillars used to allow a structure or building to stand at a distance above the ground or water. In flood plains, and on beaches or unstable ground, buildings are often constructed on stilts to protect them from damage by water, waves or shifting soil or sand. As these issues were commonly faced by many societies around the world, stilts have become synonymous with various places and cultures, particularly in South East Asia and Venice.

Lingnan architecture, or Cantonese architecture, refers to the characteristic architectural style(s) of the Lingnan region – the Southern Chinese provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi. Usually, it is referring to the architecture associated with the Cantonese people, with other peoples in the area having their own styles. This style began with the architecture of the ancient non-Han Nanyue people and absorbed certain architectural elements from the Tang Empire and Song Empire as the region sinicized in the later half of the first millennium AD.

Hokkien architecture, also called Hoklo architecture or Minnan architecture, refers to the architectural style of the Hoklo people, a Han Chinese sub-group who have historically been the dominant demographic of the Southern Chinese province of Fujian, and Taiwan, Singapore. This style shares many similarities with those of surrounding Han Chinese groups. There are, however, several features that are unique or mostly unique to Hoklo-made buildings, making many traditional buildings in Hokkien and Taiwan visually distinctive from those outside the region.

Beijing Siheyuan is a type of siheyuan in used Beijing, China. Siheyuan courtyard houses originated in Beijing and is the most prevalent type of traditional Chinese courtyard residence. Due to their high density in Beijing, the term "Siheyuan" is typically synonymous with the Beijing style. Siheyuan, along with Hutong, have become the most representative traditional architectural feature of Beijing.