Diffraction is the interference or bending of waves around the corners of an obstacle or through an aperture into the region of geometrical shadow of the obstacle/aperture. The diffracting object or aperture effectively becomes a secondary source of the propagating wave. Italian scientist Francesco Maria Grimaldi coined the word diffraction and was the first to record accurate observations of the phenomenon in 1660.

Light or visible light is electromagnetic radiation that can be perceived by the human eye. Visible light is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400–700 nanometres (nm), corresponding to frequencies of 750–420 terahertz, between the infrared and the ultraviolet.

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultraviolet, and infrared light. Light is a type of electromagnetic radiation, and other forms of electromagnetic radiation such as X-rays, microwaves, and radio waves exhibit similar properties.

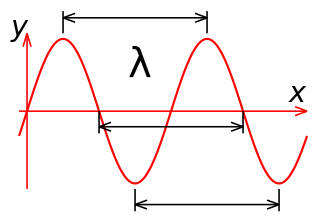

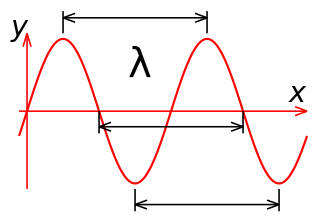

In physics and mathematics, wavelength or spatial period of a wave or periodic function is the distance over which the wave's shape repeats. In other words, it is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase on the wave, such as two adjacent crests, troughs, or zero crossings. Wavelength is a characteristic of both traveling waves and standing waves, as well as other spatial wave patterns. The inverse of the wavelength is called the spatial frequency. Wavelength is commonly designated by the Greek letter lambda (λ). The term "wavelength" is also sometimes applied to modulated waves, and to the sinusoidal envelopes of modulated waves or waves formed by interference of several sinusoids.

In physics, attenuation is the gradual loss of flux intensity through a medium. For instance, dark glasses attenuate sunlight, lead attenuates X-rays, and water and air attenuate both light and sound at variable attenuation rates.

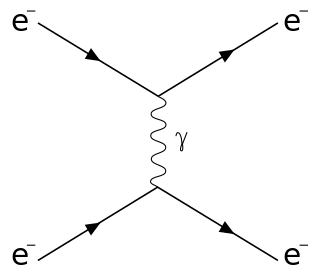

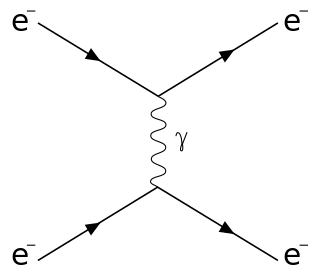

Scattering is a term used in physics to describe a wide range of physical processes where moving particles or radiation of some form, such as light or sound, are forced to deviate from a straight trajectory by localized non-uniformities in the medium through which they pass. In conventional use, this also includes deviation of reflected radiation from the angle predicted by the law of reflection. Reflections of radiation that undergo scattering are often called diffuse reflections and unscattered reflections are called specular (mirror-like) reflections. Originally, the term was confined to light scattering. As more "ray"-like phenomena were discovered, the idea of scattering was extended to them, so that William Herschel could refer to the scattering of "heat rays" in 1800. John Tyndall, a pioneer in light scattering research, noted the connection between light scattering and acoustic scattering in the 1870s. Near the end of the 19th century, the scattering of cathode rays and X-rays was observed and discussed. With the discovery of subatomic particles and the development of quantum theory in the 20th century, the sense of the term became broader as it was recognized that the same mathematical frameworks used in light scattering could be applied to many other phenomena.

In physics, Raman scattering or the Raman effect is the inelastic scattering of photons by matter, meaning that there is both an exchange of energy and a change in the light's direction. Typically this effect involves vibrational energy being gained by a molecule as incident photons from a visible laser are shifted to lower energy. This is called normal Stokes-Raman scattering.

Transition radiation (TR) is a form of electromagnetic radiation emitted when a charged particle passes through inhomogeneous media, such as a boundary between two different media. This is in contrast to Cherenkov radiation, which occurs when a charged particle passes through a homogeneous dielectric medium at a speed greater than the phase velocity of electromagnetic waves in that medium.

In physics, backscatter is the reflection of waves, particles, or signals back to the direction from which they came. It is usually a diffuse reflection due to scattering, as opposed to specular reflection as from a mirror, although specular backscattering can occur at normal incidence with a surface. Backscattering has important applications in astronomy, photography, and medical ultrasonography. The opposite effect is forward scatter, e.g. when a translucent material like a cloud diffuses sunlight, giving soft light.

Neutron scattering, the irregular dispersal of free neutrons by matter, can refer to either the naturally occurring physical process itself or to the man-made experimental techniques that use the natural process for investigating materials. The natural/physical phenomenon is of elemental importance in nuclear engineering and the nuclear sciences. Regarding the experimental technique, understanding and manipulating neutron scattering is fundamental to the applications used in crystallography, physics, physical chemistry, biophysics, and materials research.

The Tyndall effect is light scattering by particles in a colloid such as a very fine suspension. Also known as Tyndall scattering, it is similar to Rayleigh scattering, in that the intensity of the scattered light is inversely proportional to the fourth power of the wavelength, so blue light is scattered much more strongly than red light. An example in everyday life is the blue colour sometimes seen in the smoke emitted by motorcycles, in particular two-stroke machines where the burnt engine oil provides these particles. The same effect can also be observed with tobacco smoke whose fine particles also preferentially scatter blue light.

The Mainz Microtron, abbreviated MAMI, is a microtron which provides a continuous wave, high intensity, polarized electron beam with an energy up to 1.6 GeV. MAMI is the core of an experimental facility for particle, nuclear and X-ray radiation physics at the Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz (Germany). It is one of the largest campus-based accelerator facilities for basic research in Europe. The experiments at MAMI are performed by about 200 physicists of many countries organized in international collaborations.

Rutherford backscattering spectrometry (RBS) is an analytical technique used in materials science. Sometimes referred to as high-energy ion scattering (HEIS) spectrometry, RBS is used to determine the structure and composition of materials by measuring the backscattering of a beam of high energy ions (typically protons or alpha particles) impinging on a sample.

The photoacoustic Doppler effect is a type of Doppler effect that occurs when an intensity modulated light wave induces a photoacoustic wave on moving particles with a specific frequency. The observed frequency shift is a good indicator of the velocity of the illuminated moving particles. A potential biomedical application is measuring blood flow.

Angle-resolved low-coherence interferometry (a/LCI) is an emerging biomedical imaging technology which uses the properties of scattered light to measure the average size of cell structures, including cell nuclei. The technology shows promise as a clinical tool for in situ detection of dysplastic, or precancerous tissue.

Multiangle light scattering (MALS) describes a technique for measuring the light scattered by a sample into a plurality of angles. It is used for determining both the absolute molar mass and the average size of molecules in solution, by detecting how they scatter light. A collimated beam from a laser source is most often used, in which case the technique can be referred to as multiangle laser light scattering (MALLS). The insertion of the word laser was intended to reassure those used to making light scattering measurements with conventional light sources, such as Hg-arc lamps that low-angle measurements could now be made. Until the advent of lasers and their associated fine beams of narrow width, the width of conventional light beams used to make such measurements prevented data collection at smaller scattering angles. In recent years, since all commercial light scattering instrumentation use laser sources, this need to mention the light source has been dropped and the term MALS is used throughout.

Speckle, speckle pattern, or speckle noise is a granular noise texture degrading the quality as a consequence of interference among wavefronts in coherent imaging systems, such as radar, synthetic aperture radar (SAR), medical ultrasound and optical coherence tomography. Speckle is not external noise; rather, it is an inherent fluctuation in diffuse reflections, because the scatterers are not identical for each cell, and the coherent illumination wave is highly sensitive to small variations in phase changes.

Ultrasound-modulated optical tomography (UOT), also known as Acousto-Optic Tomography (AOT), is a hybrid imaging modality that combines light and sound; it is a form of tomography involving ultrasound. It is used in imaging of biological soft tissues and has potential applications for early cancer detection. As a hybrid modality which uses both light and sound, UOT provides some of the best features of both: the use of light provides strong contrast and sensitivity ; these two features are derived from the optical component of UOT. The use of ultrasound allows for high resolution, as well as a high imaging depth. However, the difficulty of tackling the two fundamental problems with UOT have caused UOT to evolve relatively slowly; most work in the field is limited to theoretical simulations or phantom / sample studies.

Cherenkov radiation is electromagnetic radiation emitted when a charged particle passes through a dielectric medium at a speed greater than the phase velocity of light in that medium. A classic example of Cherenkov radiation is the characteristic blue glow of an underwater nuclear reactor. Its cause is similar to the cause of a sonic boom, the sharp sound heard when faster-than-sound movement occurs. The phenomenon is named after Soviet physicist Pavel Cherenkov.

A random laser (RL) is a laser in which optical feedback is provided by scattering particles. As in conventional lasers, a gain medium is required for optical amplification. However, in contrast to Fabry–Pérot cavities and distributed feedback lasers, neither reflective surfaces nor distributed periodic structures are used in RLs, as light is confined in an active region by diffusive elements that either may or may not be spatially distributed inside the gain medium.