The argument from morality is an argument for the existence of God. Arguments from morality tend to be based on moral normativity or moral order. Arguments from moral normativity observe some aspect of morality and argue that God is the best or only explanation for this, concluding that God must exist. Arguments from moral order are based on the asserted need for moral order to exist in the universe. They claim that, for this moral order to exist, God must exist to support it. The argument from morality is noteworthy in that one cannot evaluate the soundness of the argument without attending to almost every important philosophical issue in meta-ethics.

Immanuel Kant was an influential German philosopher in the Age of Enlightenment. In his doctrine of transcendental idealism, he argued that space, time, and causation are mere sensibilities; "things-in-themselves" exist, but their nature is unknowable. In his view, the mind shapes and structures experience, with all human experience sharing certain structural features. He drew a parallel to the Copernican revolution in his proposition that worldly objects can be intuited a priori ('beforehand'), and that intuition is therefore independent from objective reality. Kant believed that reason is the source of morality, and that aesthetics arise from a faculty of disinterested judgment. Kant's views continue to have a major influence on contemporary philosophy, especially the fields of epistemology, ethics, political theory, and post-modern aesthetics.

Philosophy of law is a branch of philosophy that examines the nature of law and law's relationship to other systems of norms, especially ethics and political philosophy. It asks questions like "What is law?", "What are the criteria for legal validity?", and "What is the relationship between law and morality?" Philosophy of law and jurisprudence are often used interchangeably, though jurisprudence sometimes encompasses forms of reasoning that fit into economics or sociology.

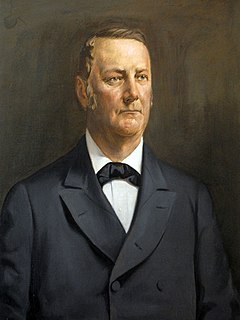

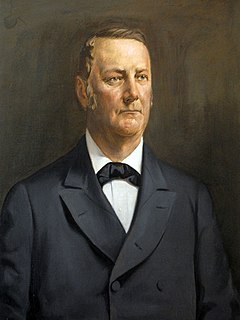

Sir John Pentland Mahaffy, was an Irish classicist and polymathic scholar.

Henry Sidgwick was an English utilitarian philosopher and economist. He was the Knightbridge Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Cambridge from 1883 until his death, and is best known in philosophy for his utilitarian treatise The Methods of Ethics. He was one of the founders and first president of the Society for Psychical Research and a member of the Metaphysical Society and promoted the higher education of women. His work in economics has also had a lasting influence.

German idealism was a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It began as a reaction to Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason. German idealism was closely linked with both Romanticism and the revolutionary politics of the Enlightenment.

Johann Georg Hamann was a German Lutheran philosopher from Königsberg known as the “the Magus of the North”, whose work was used by his student J. G. Herder as a main support of the Sturm und Drang movement, and associated by historian of ideas Isaiah Berlin with the Counter-Enlightenment. Goethe and Kierkegaard were among those who considered him to be the finest mind of his time. Long before the linguistic turn, Hamann believed epistemology should be replaced by the philosophy of language.

Richard Mervyn Hare, usually cited as R. M. Hare, was an English moral philosopher who held the post of White's Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Oxford from 1966 until 1983. He subsequently taught for a number of years at the University of Florida. His meta-ethical theories were influential during the second half of the twentieth century.

Kantianism is the philosophy of Immanuel Kant, a German philosopher born in Königsberg, Prussia. The term Kantianism or Kantian is sometimes also used to describe contemporary positions in philosophy of mind, epistemology, and ethics.

Jerome B. Schneewind is a Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at Johns Hopkins University.

John Merryman of Baltimore County, Maryland, was arrested in May 1861 and held prisoner in Fort McHenry in Baltimore and was the petitioner in the case "Ex parte Merryman" which was one of the best known habeas corpus cases of the American Civil War (1861-1865). Merryman was arrested for his involvement in the mob in Baltimore, specifically for his leadership in the destruction of telegraph lines. Merryman but was not charged, a right normally ensured by the writ of habeas corpus. The case was taken up by the federal circuit court and its current presiding judge who happened to be Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, a Democrat-leaning Marylander. The reading of Article 1, Section 9 of the Constitution was in question. Taney believed that the phrase “when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it” applied solely to Congress because of its location in Article 1. In Ex Parte Milligan, Chief Justice Taney writes, “If the high power over the liberty of the citizens now claimed was intended to be conferred on the President, it would undoubtedly be found in plain words in this article … He certainly does not faithfully execute the laws if he takes upon himself legislative power by suspending the writ of habeas corpus.” Lincoln asserted that his "war powers" gave him authority to act on this power to preserve the Union, especially since Congress could not be in session to suspend the writ. Lincoln largely ignored Taney's ruling, asking Congress when they reconvened for a special session on July 4, 1861, “Are all the laws, but one, to go unexecuted, and the government itself go to pieces, lest that one be violated?” Had the destruction of public property been allowed to continue in Maryland, Lincoln would have had to fight an insurrection in the north as well as the seceding states' armies. Thus, he concludes that suspending the writ of habeas corpus was essential to preserving the government. The executive branch could not enforce laws if people were damaging its infrastructure. The case never reached the Supreme Court, partly because in 1861 Congress passed a law which "approved and in all respects legalized and made valid ... all the acts, proclamations, and orders of the President of the United States respecting the army and navy ... as if they had been done under the previous express authority and direction of the Congress."

A maxim is a concise expression of a fundamental moral rule or principle, whether considered as objective or subjective contingent on one's philosophy. A maxim is often pedagogical and motivates specific actions. The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy defines it as:

Generally any simple and memorable rule or guide for living; for example, 'neither a borrower nor a lender be'. Tennyson speaks of 'a little hoard of maxims preaching down a daughter's heart, and maxims have generally been associated with a 'folksy' or 'copy-book' approach to morality.

The Metaphysics of Morals is a 1797 work of political and moral philosophy by Immanuel Kant.

Kantian ethics refers to a deontological ethical theory ascribed to the German philosopher Immanuel Kant. The theory, developed as a result of Enlightenment rationalism, is based on the view that the only intrinsically good thing is a good will; an action can only be good if its maxim – the principle behind it – is duty to the moral law. Central to Kant's construction of the moral law is the categorical imperative, which acts on all people, regardless of their interests or desires. Kant formulated the categorical imperative in various ways. His principle of universalizability requires that, for an action to be permissible, it must be possible to apply it to all people without a contradiction occurring. If a contradiction occurs the act violates Aristotle's "Non-contradiction" concept which states that just actions cannot lead to contradictions. Kant's formulation of humanity, the second section of the Categorical Imperative, states that as an end in itself humans are required never to treat others merely as a means to an end, but always, additionally, as ends in themselves. The formulation of autonomy concludes that rational agents are bound to the moral law by their own will, while Kant's concept of the Kingdom of Ends requires that people act as if the principles of their actions establish a law for a hypothetical kingdom. Kant also distinguished between perfect and imperfect duties. A perfect duty, such as the duty not to lie, always holds true; an imperfect duty, such as the duty to give to charity, can be made flexible and applied in particular time and place.

The analytic–synthetic distinction is a semantic distinction, used primarily in philosophy to distinguish propositions into two types: analytic propositions and synthetic propositions. Analytic propositions are true by virtue of their meaning, while synthetic propositions are true by how their meaning relates to the world. However, philosophers have used the terms in very different ways. Furthermore, philosophers have debated whether there is a legitimate distinction.

Michael Friedman is an American philosopher of science, best known for his work on scientific explanation, philosophy of physics and Immanuel Kant. Friedman has also done important historical work on figures in Continental philosophy such as Martin Heidegger and Ernst Cassirer.

Mary J. Gregor was an American author, translator, and professor. She was a Kant scholar and Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at San Diego State University, best known for translating the works of the German philosopher Immanuel Kant.

Allen William Wood is an American philosopher specializing in the work of Immanuel Kant and German Idealism, with particular interests in ethics and social philosophy. He is the Ruth Norman Halls professor of philosophy at Indiana University and has held professorships and visiting appointments at numerous universities in the United States and Europe. In addition to popularising and clarifying the ethical thought of Immanuel Kant, Wood has also mounted arguments against the validity of 'trolley problems' in moral philosophy.

John Frederick Stanford (1815–1880) was an English barrister, literary scholar, and politician.

The Sieve of Eratosthenes is a 1999 sculpture by Mark di Suvero, installed on the Stanford University campus in Stanford, California, United States.