The Picts were a group of peoples in what is now Scotland north of the Firth of Forth, in the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and details of their culture can be gleaned from early medieval texts and Pictish stones. The name Picti appears in written records as an exonym from the late third century AD. They are assumed to have been descendants of the Caledonii and other northern Iron Age tribes. Their territory is referred to as "Pictland" by modern historians. Initially made up of several chiefdoms, it came to be dominated by the Pictish kingdom of Fortriu from the seventh century. During this Verturian hegemony, Picti was adopted as an endonym. This lasted around 160 years until the Pictish kingdom merged with that of Dál Riata to form the Kingdom of Alba, ruled by the House of Alpin. The concept of "Pictish kingship" continued for a few decades until it was abandoned during the reign of Caustantín mac Áeda.

Dál Riata or Dál Riada was a Gaelic kingdom that encompassed the western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel. At its height in the 6th and 7th centuries, it covered what is now Argyll in Scotland and part of County Antrim in Northern Ireland. After a period of expansion, Dál Riata eventually became associated with the Gaelic Kingdom of Alba.

Strathclyde was a Brittonic kingdom in northern Britain during the Middle Ages. It comprised parts of what is now southern Scotland and North West England, a region the Welsh tribes referred to as Yr Hen Ogledd. At its greatest extent in the 10th century, it stretched from Loch Lomond to the River Eamont at Penrith. Strathclyde seems to have been annexed by the Goidelic-speaking Kingdom of Alba in the 11th century, becoming part of the emerging Kingdom of Scotland.

In Celtic cultures, a bard is a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise the patron's own activities.

The Culdees were members of ascetic Christian monastic and eremitical communities of Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England in the Middle Ages. Appearing first in Ireland and then in Scotland, subsequently attached to cathedral or collegiate churches; they lived in monastic fashion though not taking monastic vows.

Áedán mac Gabráin, also written as Aedan, was a king of Dál Riata from c. 574 until c. 609 AD. The kingdom of Dál Riata was situated in modern Argyll and Bute, Scotland, and parts of County Antrim, Ireland. Genealogies record that Áedán was a son of Gabrán mac Domangairt.

Fergus Mór mac Eirc was a possible king of Dál Riata. He was the son of Erc of Dalriada.

An ollam or ollamh, plural ollomain, in early Irish literature, was a master in a particular trade or skill.

Brehon is a term for a historical arbitration, mediative and judicial role in Gaelic culture. Brehons were part of the system of Early Irish law, which was also simply called "Brehon law". Brehons were judges, close in importance to the chiefs.

The origins of the Kingdom of Alba pertain to the origins of the Kingdom of Alba, or the Gaelic Kingdom of Scotland, either as a mythological event or a historical process, during the Early Middle Ages.

The Hill of Uisneach or Ushnagh is a hill and ancient ceremonial site in the barony of Rathconrath in County Westmeath, Ireland. It is a protected national monument. It consists of numerous monuments and earthworks—prehistoric and medieval—including a probable megalithic tomb, burial mounds, enclosures, standing stones, holy wells and a medieval road. Uisneach is near the geographical centre of Ireland, and in Irish mythology it is deemed to be the symbolic and sacred centre of the island. It was said to be the burial place of the mythical Tuatha Dé Danann, and a place of assembly associated with the druids and the festival of Bealtaine.

The Ó Dálaigh were a learned Irish bardic family who first came to prominence early in the 12th century, when Cú Connacht Ó Dálaigh was described as "The first Ollamh of poetry in all Ireland".

Gaelic Ireland was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late prehistoric era until the 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Normans conquered parts of Ireland in the 1170s. Thereafter, it comprised that part of the country not under foreign dominion at a given time. For most of its history, Gaelic Ireland was a "patchwork" hierarchy of territories ruled by a hierarchy of kings or chiefs, who were chosen or elected through tanistry. Warfare between these territories was common. Traditionally, a powerful ruler was acknowledged as High King of Ireland. Society was made up of clans and, like the rest of Europe, was structured hierarchically according to class. Throughout this period, the economy was mainly pastoral and money was generally not used. A Gaelic Irish style of dress, music, dance, sport and art can be identified, with Irish art later merging with Anglo-Saxon styles to create Insular art.

Scotland was divided into a series of kingdoms in the early Middle Ages, i.e. between the end of Roman authority in southern and central Britain from around 400 AD and the rise of the kingdom of Alba in 900 AD. Of these, the four most important to emerge were the Picts, the Gaels of Dál Riata, the Britons of Alt Clut, and the Anglian kingdom of Bernicia. After the arrival of the Vikings in the late 8th century, Scandinavian rulers and colonies were established on the islands and along parts of the coasts. In the 9th century, the House of Alpin combined the lands of the Scots and Picts to form a single kingdom which constituted the basis of the Kingdom of Scotland.

Many types of trees found in the Celtic nations are considered to be sacred, whether as symbols, or due to medicinal properties, or because they are seen as the abode of particular nature spirits. Historically and in folklore, the respect given to trees varies in different parts of the Celtic world. On the Isle of Man, the phrase 'fairy tree' often refers to the elder tree. The medieval Welsh poem Cad Goddeu is believed to contain Celtic tree lore, possibly relating to the crann ogham, the branch of the ogham alphabet where tree names are used as mnemonic devices.

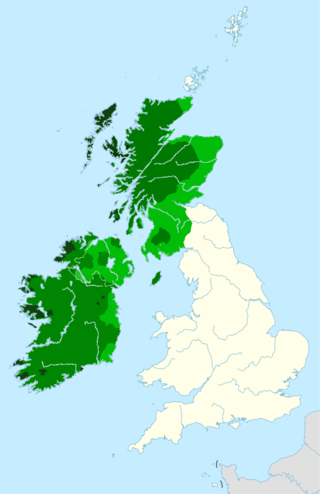

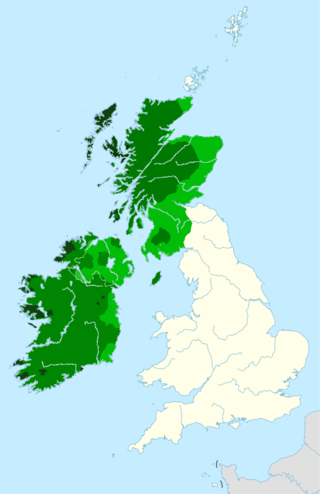

The Gaels are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languages comprising Irish, Manx and Scottish Gaelic.

The Vacomagi were a people of ancient Britain, known only from a single mention of them by the geographer Claudius Ptolemy. Their principal places are known from Ptolemy's map c.150 of Albion island of Britannia – from the First Map of Europe.

The Ollamh Érenn or Chief Ollam of Ireland was a professional title of Gaelic Ireland.

Ewan Campbell is a Scottish archaeologist and author, who serves as the senior lecturer of archaeology at the University of Glasgow. An author of a number of books, he is perhaps best known as the originator of the historical revisionist thesis that the Dál Riata did not originate from Ireland. He has also authored works about Dunadd and Forteviot.