Edward Baines (1774–1848) was the editor and proprietor of the Leeds Mercury,, politician, and author of historical and geographic works of reference. On his death in 1848, the Leeds Intelligencer described his as "one who has earned for himself an indisputable title to be numbered among the notable men of Leeds"

Samuel Bamford, was an English radical reformer and writer born in Middleton, Lancashire. He wrote in and on the subject of northern English dialect.

The London Corresponding Society (LCS) was a British Radical organisation, with a membership consisting primarily of artisans, tradesmen, and shopkeepers. At its peak, the society boasted roughly 3,000 dues-paying members who shared the goal of reforming the political system. Formed in 1792 by Thomas Hardy, the society's key mission was to ensure universal suffrage for British men and annual parliaments. Due to the perceived French revolutionary influence on the society and its calls for radical political change, the government of William Pitt the Younger, bitterly opposed it, accusing it on two occasions of plotting to assassinate the King, and putting its key leaders on trial in 1794 for treason. However, due to the transparent falsity of the government's claims, those leaders, including Hardy, John Thelwall, and John Horne Tooke, were all acquitted. After exerting "undue influence" on the European political climate in the last decade of the 18th century, the LCS and other organisations like it were outlawed by a 1799 Parliamentary Act, and efforts to maintain an underground organisation were stymied by their outlaw status and financial troubles and mismanagement.

William Cobbett was an English pamphleteer, farmer, journalist and member of parliament born in Farnham, Surrey. He believed that reforming Parliament, including abolishing "rotten boroughs", would ease the poverty of farm labourers. Relentlessly he sought an end to borough-mongers, sinecurists and "tax-eaters". He opposed the Corn Laws, which imposed a tax on imported grain. Early in life he was a loyal devotee of King and Country, but he later pushed for radicalism, which helped the Reform Act 1832 and his election that year as one of two MPs for the newly enfranchised borough of Oldham. He strongly advocated of Catholic Emancipation. His polemics cover subjects from political reform to religion. His best known book is Rural Rides.

Henry "Orator" Hunt was a British radical speaker and agitator remembered as a pioneer of working-class radicalism and an important influence on the later Chartist movement. He advocated parliamentary reform and the repeal of the Corn Laws.

The Radicals were a loose parliamentary political grouping in Great Britain and Ireland in the early to mid-19th century, who drew on earlier ideas of radicalism and helped to transform the Whigs into the Liberal Party.

Sir Francis Burdett, 5th Baronet was an English reformist politician, the son of Francis Burdett and his wife Eleanor, daughter of William Jones of Ramsbury Manor, Wiltshire, and grandson of Sir Robert Burdett, Bart. From 1820 until his death he lived at 25 St James's Place.

John Cartwright was an English naval officer, Nottinghamshire militia major and prominent campaigner for parliamentary reform. He subsequently became known as the Father of Reform. His younger brother Edmund Cartwright became famous as the inventor of the power loom.

The term "Radical", during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, identified proponents of democratic reform, in what subsequently became the parliamentary Radical Movement.

Richard Carlile was an important agitator for the establishment of universal suffrage and freedom of the press in the United Kingdom.

The publisher Thomas Jonathan Wooler was active in the Radical movement of early 19th century Britain, best known for his satirical journal The Black Dwarf.

The Blanketeers or Blanket March was a demonstration organised in Manchester in March 1817. The intention was for the participants, who were mainly Lancashire weavers, to march to London and petition the Prince Regent over the desperate state of the textile industry in Lancashire, and to protest over the recent suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act. The march was broken up violently and its leaders imprisoned. The Blanketeers formed part of a series of protests and calls for reform that culminated in the Peterloo massacre and the Six Acts.

Maurice Margarot (1745–1815) is most notable for being one of the founding members of the London Corresponding Society, a radical society demanding parliamentary reform in the late eighteenth century.

John Fielden was a British industrialist and Radical Member of Parliament for Oldham (1832–1847).

John Thelwall was a radical British orator, writer, political reformer, journalist, poet, elocutionist and speech therapist.

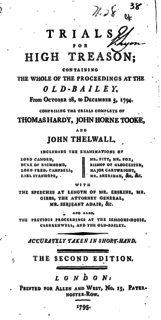

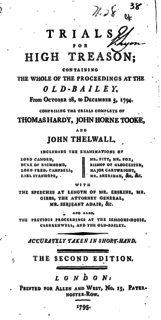

The 1794 Treason Trials, arranged by the administration of William Pitt, were intended to cripple the British radical movement of the 1790s. Over thirty radicals were initially arrested; three were tried for high treason: Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke and John Thelwall. In a repudiation of the government's policies, they were acquitted by three separate juries in November 1794 to great public rejoicing. The treason trials were an extension of the sedition trials of 1792 and 1793 against parliamentary reformers in both England and Scotland.

William Benbow was a nonconformist preacher, pamphleteer, pornographer and publisher, and a prominent figure of the Reform Movement in Manchester and London. He worked with William Cobbett on the radical newspaper Political Register, and spent time in prison as a consequence of his writing, publishing and campaigning activities. He has been credited with formulating and popularising the idea of a general strike for the purpose of political reform.

Edward Smith (1839–1919) was an English biographer. A Fellow of the Statistical Society, Smith was awarded its Howard Medal in 1875, for an essay on "The State of the Dwellings of the Poor [...]", then published as The Peasant's Home.

The Reform movement was a political movement in British Canada in the early 19th century.

The Seditious Meetings Act 1817 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland which made it illegal to hold a meeting of more than 50 people.