Design features of language

Vocal-auditory channel Refers to the idea that speaking/hearing is the mode humans use for language. When Hockett first defined this feature, it did not take sign language into account, which reflects the ideology of orality that was prevalent during the time. [3] This feature has since been modified to include other channels of language, such as tactile-visual or chemical-olfactory.

Broadcast transmission and directional reception When humans speak, sounds are transmitted in all directions; however, listeners perceive the direction from which the sounds are coming. Similarly, signers broadcast to potentially anyone within the line of sight, while those watching see who is signing. This is characteristic of most forms of human and animal communication.

Transitoriness Also called rapid fading, transitoriness refers to the temporary quality of language. Language sounds exist for only a brief period of time, after which they are no longer perceived. Sound waves quickly disappear once a speaker stops speaking. This is also true of signs. In contrast, other forms of communication such as writing and Inka khipus (knot-tying) are more permanent.

Interchangeability Refers to the idea that humans can give and receive identical linguistic signals; humans are not limited in the types of messages they can say/hear. One can say "I am a boy" even if one is a girl. This is not to be confused with lying (prevarication): The importance is that a speaker can physically create any and all messages regardless of their truth or relation to the speaker. In other words, anything that one can hear, one can also say.

Not all species possess this feature. For example, in order to communicate their status, queen ants produce chemical scents that no other ants can produce (see animal communication below).

Total feedback Speakers of a language can hear their own speech and can control and modify what they are saying as they say it. Similarly, signers see, feel, and control their signing.

Specialization The purpose of linguistic signals is communication and not some other biological function. When humans speak or sign, it is generally intentional.

An example of non-specialized communication is dog panting. When a dog pants, it often communicates to its owner that it is hot or thirsty; however, the dog pants in order to cool itself off. This is a biological function, and the communication is a secondary matter.

Semanticity Specific sound signals are directly tied to certain meanings.

Arbitrariness Languages are generally made up of both arbitrary and iconic symbols. In spoken languages, iconicity takes the form of onomatopoeia (e.g., "murmur" in English, "māo" [cat] in Mandarin). For the vast majority of other symbols, there is no intrinsic or logical connection between a sound form (signal) and what it refers to. Almost all names a human language attributes an object are thus arbitrary: the word "car" is nothing like an actual car. Spoken words are really nothing like the objects they represent. This is further demonstrated by the fact that different languages attribute very different names to the same object. Signed languages are transmitted visually and this allows for a certain degree of iconicity ("cup", "me," "up/down", etc. in ASL). For example, in the ASL sign HOUSE, the hands are flat and touch in a way that resembles the roof and walls of a house. [4] [note 1] However, many other signs are not iconic, and the relationship between form and meaning is arbitrary. Thus, while Hockett did not account for the possibility of non-arbitrary form-meaning relationships, the principle still generally applies.

Discreteness Linguistic representations can be broken down into small discrete units which combine with each other in rule-governed ways. They are perceived categorically, not continuously. For example, English marks number with the plural morpheme /s/, which can be added to the end of any noun. The plural morpheme is perceived categorically, not continuously: we cannot express smaller or larger quantities by varying how loudly we pronounce the /s/.

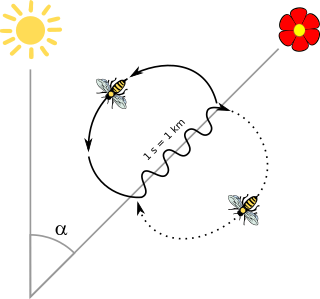

Displacement Displacement refers to the idea that humans can talk about things that are not physically present or that do not even exist. Speakers can talk about the past and the future, and can express hopes and dreams. A human's speech is not limited to here and now. Displacement is one of the features that separates human language from other forms of primate communication.

Productivity Productivity refers to the idea that language-users can create and understand novel utterances. Humans are able to produce an unlimited amount of utterances. Also related to productivity is the concept of grammatical patterning, which facilitates the use and comprehension of language. Language is not stagnant, but is constantly changing. New idioms are created all the time and the meaning of signals can vary depending on the context and situation.

Traditional transmission Also known as cultural transmission, traditional transmission is the idea that, while humans are born with innate language capabilities, language is learned after birth in a social setting. It differs critically from Chomsky's idea of Universal Grammar but rather purports that people learn how to speak by interacting with experienced language users. Significantly, language and culture are woven together in this construct, functioning hand in hand for language acquisition.

Duality of patterning Meaningful messages are made up of distinct smaller meaningful units (words and morphemes) which themselves are made up of distinct smaller, meaningless units (phonemes).

Prevarication Prevarication is the ability to lie or deceive. When using language, humans can make false or meaningless statements. This is an important distinction made of human communication, i.e. language as compared to animal communication. While animal communication can display a few other design features as proposed by Hockett, animal communication is unable to lie or make up something that does not exist or have referents.

Reflexiveness Humans can use language to talk about language. Also a very defining feature of human language, reflexiveness is a trait not shared by animal communication. With reflexiveness, humans can describe what language is, talk about the structure of language, and discuss the idea of language with others using language.

Learnability Language is teachable and learnable. In the same way, as a speaker learns their first language, the speaker is able to learn other languages. It is worth noting that young children learn language with competence and ease; however, language acquisition is constrained by a critical period such that it becomes more difficult once children pass a certain age.