The Epimenides paradox reveals a problem with self-reference in logic.

Begging the question is an informal fallacy that occurs when an argument's premises assume the truth of the conclusion, instead of supporting it. It is a type of circular reasoning: an argument that requires that the desired conclusion be true. This often occurs in an indirect way such that the fallacy's presence is hidden, or at least not easily apparent.

A syllogism is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two or more propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true.

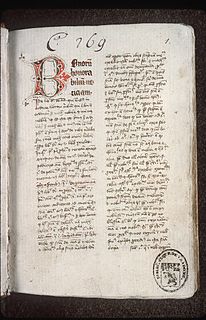

The Summa Logicae is a textbook on logic by William of Ockham. It was written around 1323.

Marsilius of Inghen was a medieval Dutch Scholastic philosopher who studied with Albert of Saxony and Nicole Oresme under Jean Buridan. He was Magister at the University of Paris as well as at the University of Heidelberg from 1386 to 1396.

The Prior Analytics is Aristotle's work on deductive reasoning, which is known as his syllogistic. Being one of the six extant Aristotelian writings on logic and scientific method, it is part of what later Peripatetics called the Organon. Modern work on Aristotle's logic builds on the tradition started in 1951 with the establishment by Jan Lukasiewicz of a revolutionary paradigm. The Jan Łukasiewicz approach was replaced in the early 1970s in a series of papers by John Corcoran and Timothy Smiley —which inform modern translations of Prior Analytics by Robin Smith in 1989 and Gisela Striker in 2009.

The Organon is the standard collection of Aristotle's six works on logic. The name Organon was given by Aristotle's followers, the Peripatetics. They are as follows:

Albert of Saxony was a German philosopher known for his contributions to logic and physics. He was bishop of Halberstadt from 1366 until his death.

William of Sherwood or William Sherwood, with numerous variant spellings, was a medieval English scholastic philosopher, logician, and teacher. Little is known of his life, but he is thought to have studied in Paris, was a master at Oxford in 1252, treasurer of Lincoln from 1254/1258 onwards, and a rector of Aylesbury.

The Oxford Calculators were a group of 14th-century thinkers, almost all associated with Merton College, Oxford; for this reason they were dubbed "The Merton School". These men took a strikingly logico-mathematical approach to philosophical problems. The key "calculators", writing in the second quarter of the 14th century, were Thomas Bradwardine, William Heytesbury, Richard Swineshead and John Dumbleton. These men built on the slightly earlier work of Walter Burley and Gerard of Brussels.

In the history of logic, the term logica nova refers to a subdivision of the logical tradition of Western Europe, as it existed around the middle of the thirteenth century. According to the availability at the time of the logical works of Aristotle in Latin translation, there was a logica vetus and the logica nova.

Bryson of Heraclea was an ancient Greek mathematician and sophist who contributed to solving the problem of squaring the circle and calculating pi.

Medieval philosophy is a term used to refer to the philosophy that existed through the Middle Ages, the period roughly extending from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century to the Renaissance in the 15th century. Medieval philosophy, understood as a project of independent philosophical inquiry, began in Baghdad, in the middle of the 8th century, and in France, in the itinerant court of Charlemagne, in the last quarter of the 8th century. It is defined partly by the process of rediscovering the ancient culture developed in Greece and Rome during the Classical period, and partly by the need to address theological problems and to integrate sacred doctrine with secular learning.

Stoic logic is the system of propositional logic developed by the Stoic philosophers in ancient Greece. It was one of the two great systems of logic in the classical world. It was largely built and shaped by Chrysippus, the third head of the Stoic school in the 3rd-century BCE. Chrysippus's logic differed from Aristotle's term logic because it was based on the analysis of propositions rather than terms. The smallest unit in Stoic logic is an assertible which is the content of a statement such as "it is day". Assertibles have a truth-value such that at any moment of time they are either true or false. Compound assertibles can be built up from simple ones through the use of logical connectives. The resulting syllogistic was grounded on five basic indemonstrable arguments to which all other syllogisms were claimed to be reducible.

The No–no paradox is a distinctive paradox belonging to the family of the semantic paradoxes. It derives its name from the fact that it consists of two sentences each simply denying what the other says.

The knower paradox is a paradox belonging to the family of the paradoxes of self-reference. Informally, it consists in considering a sentence saying of itself that it is not known, and apparently deriving the contradiction that such sentence is both not known and known.