Related Research Articles

Second-wave feminism was a period of feminist activity that began in the early 1960s and lasted roughly two decades, ending with the feminist sex wars in the early 1980s and being replaced by third-wave feminism in the early 1990s. It occurred throughout the Western world and aimed to increase women's equality by building on the feminist gains of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Gemma Hussey is an Irish former Fine Gael politician who served as Minister for Social Welfare from 1986 to 1987, Minister for Labour from January 1987 to March 1987, Minister for Education from 1982 to 1986, Leader of the Seanad and Leader of Fine Gael in the Seanad from 1981 to 1982. She served as a Teachta Dála (TD) for the Wicklow constituency from 1982 to 1989. She also served as a Senator for the National University from 1977 to 1982.

Events in the year 1974 in Ireland.

Nell McCafferty is an Irish journalist, playwright, civil rights campaigner and feminist. She has written for The Irish Press, The Irish Times, Sunday Tribune, Hot Press and The Village Voice.

Nuala O'Faolain was an Irish journalist, TV producer, book reviewer, teacher and writer. She became well known after the publication of her memoirs Are You Somebody? and Almost There. She wrote a biography of Irish criminal Chicago May and two novels.

Declan Costello was an Irish judge, barrister and Fine Gael politician who served as President of the High Court from 1995 to 1998, a Judge of the High Court from 1977 to 1998 and Attorney General of Ireland from 1973 to 1977. He also served as a Teachta Dála (TD) for the Dublin North-West constituency from 1951 to 1969 and for the Dublin South-West constituency from 1973 to 1977.

Nuala Fennell was an Irish Fine Gael politician, economist and activist who served as Minister of State from December 1982 to January 1987 with responsibility for Women's Affairs and Family Law. She served as a Teachta Dála (TD) for the Dublin South from 1981 to 1987 and 1989 to 1992. She also served as a Senator from 1987 to 1989.

Mary Kenny is an Irish journalist, broadcaster and playwright. A founding member of the Irish Women's Liberation Movement, she was one of the country's first and foremost feminists, often contributes columns to the Irish Independent and has been described as "the grand dame of Irish journalism". She is based in England.

Revolutionary Marxist Group was a Trotskyist organisation in Ireland during the 1970s.

June Levine was an Irish journalist, novelist and feminist, who played a central part in the Irish women's movement.

Feminism has played a major role in shaping the legal and social position of women in present-day Ireland. The role of women has been influenced by numerous legal changes in the second part of the 20th century, especially in the 1970s.

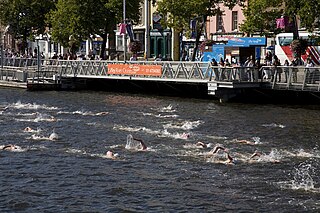

The Liffey Swim, currently titled the Jones Engineering Dublin City Liffey Swim, is an annual race in Dublin's main river, the Liffey, and is one of Ireland's most famous traditional sporting events. The race is managed by a voluntary not-for-profit organisation, Leinster Open Sea. The 100th Liffey Swim over a 2.2 km course took place on Saturday 3 August 2019, starting at the Rory O’More Bridge beside the Guinness Brewery and finishing at North Wall Quay in front of the Customs House.

Margaret Gaj was a Dublin restaurant owner and political activist.

The National LGBT Federation (NXF) is a non-governmental organisation in Dublin, Ireland, which focuses on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights.

The Contraceptive Train was a women's rights activism event which took place on 22 May 1971. Members of the Irish Women's Liberation Movement (IWLM), in protest against the law prohibiting the importation and sale of contraceptives in the Republic of Ireland, travelled to Belfast to purchase contraceptives.

Ailbhe Smyth is an Irish academic, feminist and LGBTQ activist. She was the founding director of the Women's Education, Resource and Research Centre (WERRC), University College Dublin (UCD).

The women's liberation movement in Europe was a radical feminist movement that started in the late 1960s and continued through the 1970s and in some cases into the early 1980s. Inspired by developments in North America and triggered by the growing presence of women in the labour market, the movement soon gained momentum in Britain and the Scandinavian countries. In addition to improvements in working conditions and equal pay, liberationists fought for complete autonomy for women's bodies including their right to make their own decisions regarding contraception and abortion, and more independence in sexuality.

Máirín de Burca is an Irish writer, journalist and activist. She is particularly well known in her role with Mary Anderson, of forcing a change in Irish law to enable women to serve on juries.

Máirín Johnston is an Irish author and feminist from The Liberties in Dublin, Ireland who worked to bring contraceptives into Dublin in 1971 with the Irish Women's Liberation Movement (IWLM). Johnston has authored Dublin Belles: Conversations with Dublin Women and Around the Banks of Pimlico, as well as the children's book The Pony Express, which won a Bisto Merit Award in 1994.

Mary Maher was an American-born Irish trade unionist, feminist, and journalist. She was a founder of the Irish Women's Liberation Movement and the first women's editor at The Irish Times newspaper, where she worked for 36 years.

References

- ↑ "Irish Women's Liberation Movement" (PDF). Trinity College, Dublin. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ "Celebrating Sisterhood". The Irish Times. 26 May 2010. Retrieved 21 August 2015– via Newspaper Source – EBSCOhost.

- 1 2 "Ten Things an Irish Woman Could Not Do in 1970 (And Be Prepared to Cringe...)". Galway Advertiser. 13 December 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Farren, Grainne (21 May 2006). "The Essential Story of How Irish Women Cast Off Their Chains". Independent. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ↑ Meehan, Ciara (27 May 2013). "1970s Ireland: A Good Place For Women?". Ciara Meehan. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ↑ Sweetman, Rosita (7 February 2011). "The Matriarch Who Served up Stew and Social Progress". Independent. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ↑ "The Liffey Press Mondays at Gaj's: The Story of the Irish Women's Liberation Movement". The Liffey Press. Archived from the original on 18 December 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ↑ McCafferty, Nell. "Ireland: Breaking the Shackles". 1968: Memories and Legacies of a Global Revolt (PDF). pp. 216–218. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 Flynn, Mary (2002). "Mary Flynn (1946- )". The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing. Vol. 5. New York: New York University Press. pp. 203–205. ISBN 0814799078.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Franks, Jill (2013). British and Irish Women Writers and the Women's Movement: Six Literary Voices of Their Time. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. 44–46. ISBN 9780786474080.

- ↑ Horgan, Goretti (2001). "Changing Women's Lives in Ireland". International Socialism Journal (91). Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 "The Women's Liberation Movement". Discovering Women in Irish History. Department of Education and Science, An Roinn Oideachais agus Eolaíochta. 2004. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ↑ "Laying the tracks to liberation: The original contraceptive train". The Irish Times . Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ↑ "Members of the Irish Women's Liberation Movement Travel to Belfast in 1971 To Buy Contraceptives". RTÉ Archives. Raidió Teilifís Éireann. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ↑ Ruane, Medb (1 May 2010). "When Irish Women Took Control of Their Destiny – And Their Bodies". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2015– via IFPA.

- ↑ Fennell, Nuala (2002). "Irish Women's Liberation Movement". The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing. Vol. 5. New York University Press. p. 202. ISBN 0814799078.

- ↑ Ferriter, Diarmaid (2012). Ambiguous Republid: Ireland in the 1970s. London: Profile Books Ltd. ISBN 9781846684685.

- ↑ "Today Irish Legal History: De Burca and Anderson v AG". Human Rights in Ireland. 12 December 2014. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2015.