Filippo Giuseppe Maria Ludovico Buonarroti, more usually referred to under the French version Philippe Buonarroti, was an Italian utopian socialist, writer, agitator, freemason, and conspirator; he was active in Corsica, France, and Geneva. His History of Babeuf’s 'Conspiracy of Equals' (1828) became a bible for revolutionaries, inspiring such leftists as Blanqui and Marx. He proposed a mutualist strategy that would revolutionize society by stages, starting from monarchy to liberalism, then to radicalism, and finally to communism.

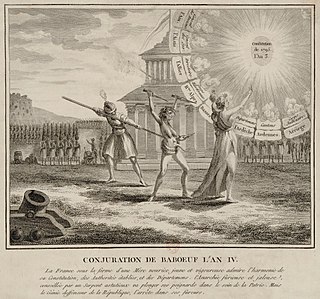

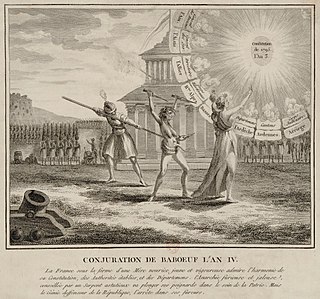

The Conspiracy of the Equals of May 1796 was a failed coup de main during the French Revolution. It was led by François-Noël Babeuf, who wanted to overthrow the Directory and replace it with an egalitarian and proto-socialist republic, inspired by Jacobin ideals.

Joseph Déjacque was a French early anarcho-communist poet and writer. Déjacque was the first recorded person to employ the term "libertarian" for himself in a political sense in a letter written in 1857, criticizing Pierre-Joseph Proudhon for his sexist views on women, his support of individual ownership of the product of labor and of a market economy, saying that "it is not the product of his or her labor that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature".

Blanquism refers to a conception of revolution generally attributed to Louis Auguste Blanqui (1805–1881) which holds that socialist revolution should be carried out by a relatively small group of highly organised and secretive conspirators. Having seized power, the revolutionaries would then use the power of the state to introduce socialism. It is considered a particular sort of "putschism"—that is, the view that political revolution should take the form of a putsch or coup d'état.

Sylvain Maréchal was a French essayist, poet, philosopher and political theorist, whose views presaged utopian socialism and communism. His views on a future golden age are occasionally described as utopian anarchism. He was editor of the newspaper Révolutions de Paris.

Fire in the Minds of Men: Origins of the Revolutionary Faith is a book about the spread of ideas written by James H. Billington, historian and Librarian of Congress. The book analyzes the ideas that inspired European revolutionary movements from the 1700s to the 1900s.

Neo-Babouvism is a term commonly used to designate a revolutionary communist current in French political theory and action in the nineteenth century.

Gustave Tridon (1841–1871) was a French revolutionary socialist, member of the First International and the Paris Commune and anti-Semite.

Karl Theodor Ferdinand Grün, also known by his alias Ernst von der Haide, was a German journalist, political theorist and socialist politician. He played a prominent role in radical political movements leading up to the Revolution of 1848 and participated in the revolution. He was an associate of Heinrich Heine, Ludwig Feuerbach, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Karl Marx, Mikhail Bakunin and other radical political figures of the era. Though less widely known today, Grün was an important figure in the German Vormärz, Young Hegelian philosophy and the democratic and socialist movements in nineteenth-century Germany. As a target of Marx's criticism, Grün played a role in the development of early Marxism; through his philosophical influence on Proudhon, he had a certain influence on the development of French socialist theory.

The Left in France was represented at the beginning of the 20th century by two main political parties: the Republican, Radical and Radical-Socialist Party and the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO), created in 1905 as a merger of various Marxist parties. But in 1914, after the assassination of the leader of the SFIO, Jean Jaurès, who had upheld an internationalist and anti-militarist line, the SFIO accepted to join the Union sacrée national front. In the aftermaths of the Russian Revolution and the Spartacist uprising in Germany, the French Left divided itself in reformists and revolutionaries during the 1920 Tours Congress, which saw the majority of the SFIO spin-out to form the French Section of the Communist International (SFIC). The early French Left was often alienated into the Republican movements.

Property is theft! is a slogan coined by French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in his 1840 book What is Property? Or, an Inquiry into the Principle of Right and of Government.

If I were asked to answer the following question: What is slavery? and I should answer in one word, It is murder!, my meaning would be understood at once. No extended argument would be required to show that the power to remove a man's mind, will, and personality, is the power of life and death, and that it makes a man a slave. It is murder. Why, then, to this other question: What is property? may I not likewise answer, It is robbery!, without the certainty of being misunderstood; the second proposition being no other than a transformation of the first?

Utopian socialism is a label used to define the first currents of modern socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet and Robert Owen.

The Communist League was an international political party established on June 1, 1847 in London, England. The organisation was formed through the merger of the League of the Just, headed by Karl Schapper and the Communist Correspondence Committee of Brussels, Belgium, in which Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels were the dominant personalities. The Communist League is regarded as the first Marxist political party and it was on behalf of this group that Marx and Engels wrote the Communist Manifesto late in 1847. The Communist League was formally disbanded in 1852, following the Cologne Communist Trial.

The League of the Just or League of Justice was a Christian communist international revolutionary organization. It was founded in 1836 by branching off from its ancestor, the League of Outlaws, which had formed in Paris in 1834. The League of the Just was largely composed of German emigrant artisans.