Checkers, also known as draughts, is a group of strategy board games for two players which involve forward movements of uniform game pieces and mandatory captures by jumping over opponent pieces. Checkers is developed from alquerque. The term "checkers" derives from the checkered board which the game is played on, whereas "draughts" derives from the verb "to draw" or "to move".

Three men's morris is an abstract strategy game played on a three by three board that is similar to tic-tac-toe. It is also related to six men's morris and nine men's morris. A player wins by forming a mill, that is, three of their own pieces in a row.

Mak-yek is a two-player abstract strategy board game played in Thailand and Myanmar. Players move their pieces as in the rook in Chess and attempt to capture their opponent's pieces through custodian and intervention capture. The game may have been first described in literature by Captain James Low a writing contributor in the 1839 work Asiatic Researches; or, Transactions of the Society, Instituted in Bengal, For Inquiring into The History, The Antiquities, The Arts and Sciences, and Literature of Asian, Second Part of the Twentieth Volume in which he wrote chapter X On Siamese Literature and documented the game as Maak yék. Another early description of the game is by H.J.R. Murray in his 1913 work A History of Chess, and the game was written as Maak-yek.

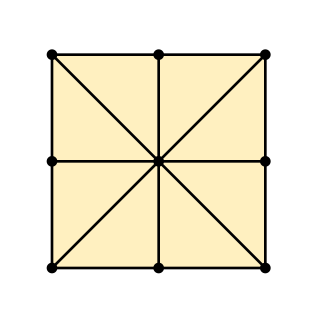

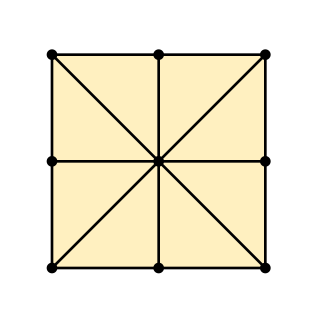

Kensington is an abstract strategy board game devised by Brian Taylor and Peter Forbes in 1979, named after London's Kensington Gardens, which contains the mosaic upon which the gameboard is patterned. It is played on a geometrical board based on the rhombitrihexagonal tiling pattern. The objective of the game is to capture a hexagon by occupying the six surrounding vertices. The game maintains an elegant simplicity while still allowing for astonishingly complex strategy. The placing and movement of tokens have been compared to nine men's morris.

Ludus latrunculorum, latrunculi, or simply latrones was a two-player strategy board game played throughout the Roman Empire. It is said to resemble chess or draughts, as it is generally accepted to be a game of military tactics. Because of the scarcity of sources, reconstruction of the game's rules and basic structure is difficult, and therefore there are multiple interpretations of the available evidence.

Hasami shogi is a variant of shogi. The game has two main variants, and all Hasami variants, unlike other shogi variants, use only one type of piece, and the winning objective is not checkmate. One main variant involves capturing all but one of the opponent's men; the other involves building an unbroken vertical or horizontal chain of five-in-a-row.

Heian shōgi is a predecessor of modern shogi. Some form of the game of Chaturanga, the ancestor of both chess and shogi, reached Japan by the 9th century, if not earlier, but the earliest surviving Japanese description of the rules dates from the early 12th century. Unfortunately, this description does not give enough information to actually play the game, but this has not stopped people from attempting to reconstruct this early form of shogi.

Morabaraba is a traditional two-player strategy board game played in South Africa and Botswana with a slightly different variation played in Lesotho. This game is known by many names in many languages, including mlabalaba, mmela, muravava, and umlabalaba. The game is similar to twelve men's morris, a variation on the Roman board game nine men's morris.

Russian draughts is a variant of draughts (checkers) played in Russia and some parts of the former USSR, as well as parts of Eastern Europe and Israel.

Fangqi is a strategy board game played traditionally throughout Northern China as a training game for weiqi (Go). Fangqi is also known as diūfāng and xiàfāng. Muslim people of Chinese origin (Dungans), brought the game with them to Central Asian countries such as Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan.

Dara is a two-player abstract strategy board game played in several countries of West Africa. In Nigeria it is played by the Dakarkari people. It is popular in Niger among the Zarma, who call it dili, and it is also played in Burkina Faso. In the Hausa language, the game is called doki which means horse. It is an alignment game related to tic-tac-toe, but far more complex. The game was invented in the 19th century or earlier. The game is also known as derrah and is very similar to Wali and Dama Tuareg.

Nine holes is a two-player abstract strategy game from different parts of the world and is centuries old. It was very popular in England. It is related to tic-tac-toe, but even more related to three men's morris, achi, tant fant, shisima, picaria, and dara, because pieces are moved on the board to create the 3 in a row. It is an alignment game.

Achi is a two-player abstract strategy game from Ghana. It is also called tapatan. It is related to tic-tac-toe, but even more related to three men's morris, Nine Holes, Tant Fant, Shisima, and Dara, because pieces are moved on the board to create the 3-in-a-row. Achi is an alignment game.

Picaria is a two-player abstract strategy game from the Zuni Native American Indians or the Pueblo Indians of the American Southwest. It is related to tic-tac-toe, but more related to three men's morris, Nine Holes, Achi, Tant Fant, and Shisima, because pieces can be moved to create the three-in-a-row. Picaria is an alignment game.

Wali is a two-player abstract strategy game from Africa. It is unknown specifically which African country the game originates from. Players attempt to form a 3 in-a-row of their pieces, and in doing so capture a piece from their opponent. The game has two phases: Drop Phase and Move Phase. Players first drop as many of their pieces as possible in the Drop Phase, then move them to form 3 in-a-rows which allows them to capture the other player's pieces in the Move Phase.

Zamma is a two-player abstract strategy game from Africa. It is especially played in Mauritania. The game is similar to alquerque and draughts. Board sizes vary, but they are square boards, such as 5x5 or 9x9 square grids with left and right diagonal lines running through several intersection points of the board. One could think of the 5x5 board as a standard alquerque board, but with additional diagonal lines, and the 9x9 board as four standard alquerque boards combined, but no additional diagonal lines are added. The initial setup is also similar to alquerque, where every space on the board is filled with each player's pieces except for the middle point of the board. Furthermore, each player's pieces are also set up on their respective half of the board. The game specifically resembles draughts in that pieces must move in the forward directions until they are crowned "Mullah" which is the equivalent of the king in draughts. The Edhayam can move in any direction. In Mauritania, the black pieces are referred to as men, and the white pieces as women. In the Sahara, short sticks represent the men, and camel dung represent the women.

Tiger and buffaloes is a two-player abstract strategy board game from Myanmar. It belongs to the hunt game family. The board is a 4x4 square grid, where pieces are placed on the intersection points and move along the lines. It is one of the smallest hunt games. Three tigers are going up against eleven buffaloes. The tigers attempt to capture as many of the buffaloes by the short leap as in draughts or alquerque. The buffaloes attempt to hem in the tigers.

Dala is a two-player abstract strategy board game from Sudan, and played especially by the Baggara tribes. The game is also called Herding the Cows. It is an alignment game with captures similar to that of the game Dara. Players first drop their pieces onto the board, and then move them orthogonally in an attempt to form 3 in-a-rows which allows a player to capture any of their opponent's piece on the board.

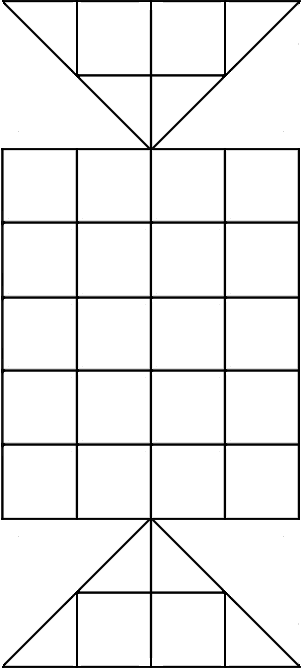

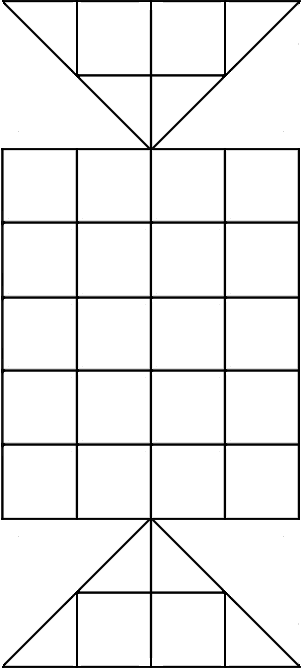

Astar is a two-player abstract strategy board game from Kyrgyzstan. It is a game similar to draughts and Alquerque as players hop over one another's pieces when capturing. However, unlike draughts and Alquerqe, Astar is played on 5×6 square grid with two triangular boards attached on two opposite sides of the grid. The board somewhat resembles those of kotu ellima, sixteen soldiers, and peralikatuma, all of which are games related to astar. However, these three games use an expanded alquerque board with a 5×5 square grid with diagonal lines. Astar uses a 5×6 grid with no diagonal lines.

This glossary of board games explains commonly used terms in board games, in alphabetical order. For a list of board games, see List of board games; for terms specific to chess, see Glossary of chess; for terms specific to chess problems, see Glossary of chess problems.