Neisseria is a large genus of bacteria that colonize the mucosal surfaces of many animals. Of the 11 species that colonize humans, only two are pathogens, N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae.

Varicella zoster virus (VZV), also known as human herpesvirus 3 or Human alphaherpesvirus 3 (taxonomically), is one of nine known herpes viruses that can infect humans. It causes chickenpox (varicella) commonly affecting children and young adults, and shingles in adults but rarely in children. VZV infections are species-specific to humans. The virus can survive in external environments for a few hours.

The DPT vaccine or DTP vaccine is a class of combination vaccines against three infectious diseases in humans: diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus. The vaccine components include diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and either killed whole cells of the bacterium that causes pertussis or pertussis antigens. The term toxoid refers to vaccines which use an inactivated toxin produced by the pathogen which they are targeted against to generate an immune response. In this way, the toxoid vaccine generates an immune response which is targeted against the toxin which is produced by the pathogen and causes disease, rather than a vaccine which is targeted against the pathogen itself. The whole cells or antigens will be depicted as either "DTwP" or "DTaP", where the lower-case "w" indicates whole-cell inactivated pertussis and the lower-case "a" stands for "acellular". In comparison to alternative vaccine types, such as live attenuated vaccines, the DTP vaccine does not contain any live pathogen, but rather uses inactivated toxoid to generate an immune response; therefore, there is not a risk of use in populations that are immune compromised since there is not any known risk of causing the disease itself. As a result, the DTP vaccine is considered a safe vaccine to use in anyone and it generates a much more targeted immune response specific for the pathogen of interest.

MeNZB was a vaccine against a specific strain of group B meningococcus, used to control an epidemic of meningococcal disease in New Zealand. Most people are able to carry the meningococcus bacteria safely with no ill effects. However, meningococcal disease can cause meningitis and sepsis, resulting in brain damage, failure of various organs, severe skin and soft-tissue damage, and death.

A conjugate vaccine is a type of subunit vaccine which combines a weak antigen with a strong antigen as a carrier so that the immune system has a stronger response to the weak antigen.

Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine, sold under the brand name Pneumovax 23, is a pneumococcal vaccine that is used for the prevention of pneumococcal disease caused by the 23 serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae contained in the vaccine as capsular polysaccharides. It is given by intramuscular or subcutaneous injection.

Neisseria meningitidis, often referred to as the meningococcus, is a Gram-negative bacterium that can cause meningitis and other forms of meningococcal disease such as meningococcemia, a life-threatening sepsis. The bacterium is referred to as a coccus because it is round, and more specifically a diplococcus because of its tendency to form pairs.

Meningococcal disease describes infections caused by the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis. It has a high mortality rate if untreated but is vaccine-preventable. While best known as a cause of meningitis, it can also result in sepsis, which is an even more damaging and dangerous condition. Meningitis and meningococcemia are major causes of illness, death, and disability in both developed and under-developed countries.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is a committee within the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that provides advice and guidance on effective control of vaccine-preventable diseases in the U.S. civilian population. The ACIP develops written recommendations for routine administration of vaccines to the pediatric and adult populations, along with vaccination schedules regarding appropriate timing, dosage, and contraindications of vaccines. ACIP statements are official federal recommendations for the use of vaccines and immune globulins in the U.S., and are published by the CDC.

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine is a pneumococcal vaccine and a conjugate vaccine used to protect infants, young children, and adults against disease caused by the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus). It contains purified capsular polysaccharide of pneumococcal serotypes conjugated to a carrier protein to improve antibody response compared to the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the use of the conjugate vaccine in routine immunizations given to children.

Hepatitis B vaccine is a vaccine that prevents hepatitis B. The first dose is recommended within 24 hours of birth with either two or three more doses given after that. This includes those with poor immune function such as from HIV/AIDS and those born premature. It is also recommended that health-care workers be vaccinated. In healthy people, routine immunization results in more than 95% of people being protected.

The Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine, also known as Hib vaccine, is a vaccine used to prevent Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) infection. In countries that include it as a routine vaccine, rates of severe Hib infections have decreased more than 90%. It has therefore resulted in a decrease in the rate of meningitis, pneumonia, and epiglottitis.

Pneumococcal infection is an infection caused by the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Jeeri Reddy an American biologist who became an entrepreneur, developing new generation preventive and therapeutic vaccines. He has been an active leader in the field of the biopharmaceutical industry, commercializing diagnostics and vaccines through JN-International Medical Corporation. He is the scientific director and president of the corporation that created the world's first serological rapid tests for Tuberculosis to facilitate acid-fast bacilli microscopy for the identification of smear-positive and negative cases. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV was achieved in South East Asia by the use of rapid tests developed by Reddy in 1999. Reddy through his Corporation donated $173,050 worth of Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) for malaria in Zambia and actively participated in the prevention of child deaths due to Malaria infections. Reddy was personally invited by the president, George W. Bush, and First Lady Laura Bush to the White House for Malaria Awareness Day sponsored by US President Malaria Initiative (PMI) on Wednesday, April 25, 2007.

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, intense headache, vomiting and neck stiffness and occasionally photophobia.

Meningococcal vaccine refers to any vaccine used to prevent infection by Neisseria meningitidis. Different versions are effective against some or all of the following types of meningococcus: A, B, C, W-135, and Y. The vaccines are between 85 and 100% effective for at least two years. They result in a decrease in meningitis and sepsis among populations where they are widely used. They are given either by injection into a muscle or just under the skin.

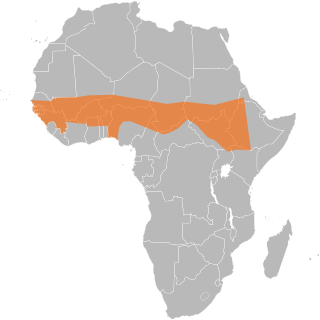

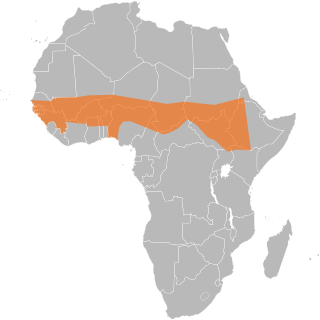

The African meningitis belt is a region in sub-Saharan Africa where the rate of incidence of meningitis is very high. It extends from Senegal to Ethiopia, and the primary cause of meningitis in the belt is Neisseria meningitidis.

MenAfriVac is a vaccine developed for use in sub-Saharan Africa for children and adults between 9 months and 29 years of age against meningococcal bacterium Neisseria meningitidis group A. The vaccine costs less than US$0.50 per dose.

Sir Andrew John Pollard is the Ashall Professor of Infection & Immunity at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of St Cross College, Oxford. He is an Honorary Consultant Paediatrician at John Radcliffe Hospital and the Director of the Oxford Vaccine Group. He is the Chief Investigator on the University of Oxford COVID-19 Vaccine trials and has led research on vaccines for many life-threatening infectious diseases including typhoid fever, Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae type b, streptococcus pneumoniae, pertussis, influenza, rabies, and Ebola.

Trudy Virginia Noller Murphy is an American pediatric infectious diseases physician, public health epidemiologist and vaccinologist. During the 1980s and 1990s, she conducted research at Southwestern Medical School in Dallas, Texas on three bacterial pathogens: Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Murphy's studies advanced understanding of how these organisms spread within communities, particularly among children attending day care centers. Her seminal work on Hib vaccines elucidated the effects of introduction of new Hib vaccines on both bacterial carriage and control of invasive Hib disease. Murphy subsequently joined the National Immunization Program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). where she led multi-disciplinary teams in the Divisions of Epidemiology and Surveillance and The Viral Hepatitis Division. Among her most influential work at CDC was on Rotashield™, which was a newly licensed vaccine designed to prevent severe diarrheal disease caused by rotavirus. Murphy and her colleagues uncovered that the vaccine increased the risk of acute bowel obstruction (intussusception). This finding prompted suspension of the national recommendation to vaccinate children with Rotashield, and led the manufacturer to withdraw the vaccine from the market. For this work Murphy received the United States Department of Health and Human Services Secretary's Award for Distinguished Service in 2000, and the publication describing this work was recognized in 2002 by the Charles C. Shepard Science Award from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.