Cyberspace is an interconnected digital environment. It is a type of virtual world popularized with the rise of the Internet. The term entered popular culture from science fiction and the arts but is now used by technology strategists, security professionals, governments, military and industry leaders and entrepreneurs to describe the domain of the global technology environment, commonly defined as standing for the global network of interdependent information technology infrastructures, telecommunications networks and computer processing systems. Others consider cyberspace to be just a notional environment in which communication over computer networks occurs. The word became popular in the 1990s when the use of the Internet, networking, and digital communication were all growing dramatically; the term cyberspace was able to represent the many new ideas and phenomena that were emerging. As a social experience, individuals can interact, exchange ideas, share information, provide social support, conduct business, direct actions, create artistic media, play games, engage in political discussion, and so on, using this global network. Cyberspace users are sometimes referred to as cybernauts.

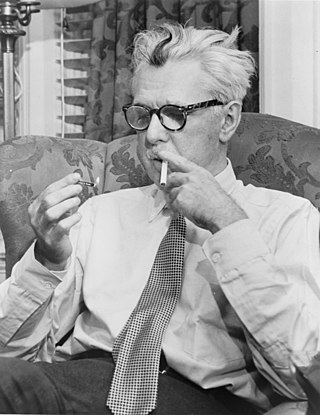

James Grover Thurber was an American cartoonist, writer, humorist, journalist and playwright. He was best known for his cartoons and short stories, published mainly in The New Yorker and collected in his numerous books.

The New Yorker is an American magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. It was founded on February 21, 1925, by Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, a reporter for The New York Times. Together with entrepreneur Raoul H. Fleischmann, they established the F-R Publishing Company and set up the magazine's first office in Manhattan. Ross remained the editor until his death in 1951, shaping the magazine's editorial tone and standards.

In computer technology and telecommunications, online indicates a state of connectivity and offline indicates a disconnected state. In modern terminology, this usually refers to an Internet connection, but could refer to any piece of equipment or functional unit that is connected to a larger system. Being online means that the equipment or subsystem is connected, or that it is ready for use.

Lester Lawrence Lessig III is an American legal scholar and political activist. He is the Roy L. Furman Professor of Law at Harvard Law School and the former director of the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics at Harvard University. He is the founder of Creative Commons and Equal Citizens. Lessig was a candidate for the Democratic Party's nomination for president of the United States in the 2016 US presidential election but withdrew before the primaries.

Sherry Turkle is an American sociologist. She is the Abby Rockefeller Mauzé Professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She obtained a BA in social studies and later a PhD in sociology and personality psychology at Harvard University. She now focuses her research on psychoanalysis and human-technology interaction. She has written several books focusing on the psychology of human relationships with technology, especially in the realm of how people relate to computational objects. Her memoir 'Empathy Diaries' received excellent critical reviews.

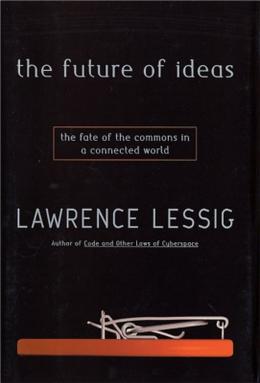

The Future of Ideas: The Fate of the Commons in a Connected World (2001) is a book by Lawrence Lessig, at the time of writing a professor of law at Stanford Law School, who is well known as a critic of the extension of the copyright term in US. It is a continuation of his previous book Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace, which is about how computer programs can restrict freedom of ideas in cyberspace.

Cyberdog was an OpenDoc-based Internet suite of applications, developed by Apple Computer for the Mac OS line of operating systems. It was introduced as a beta in February 1996 and abandoned in March 1997. The last version, Cyberdog 2.0, was released on April 28, 1997. It worked with later versions of System 7 as well as the Mac OS 8 and Mac OS 9 operating systems.

A virtual community is a social work of individuals who connect through specific social media, potentially crossing geographical and political boundaries in order to pursue mutual interests or goals. Some of the most pervasive virtual communities are online communities operating under social networking services.

Internet culture is a quasi-underground culture developed and maintained among frequent and active users of the Internet who primarily communicate with one another online as members of online communities; that is, a culture whose influence is "mediated by computer screens" and information communication technology, specifically the Internet.

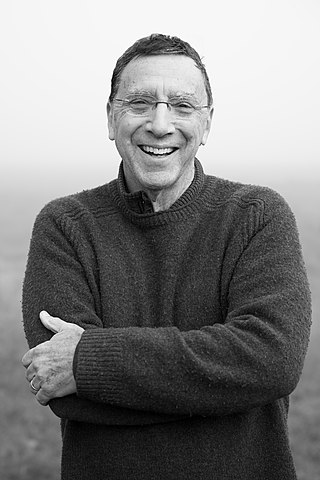

John Gregory Markoff is a journalist best known for his work covering technology at The New York Times for 28 years until his retirement in 2016, and a book and series of articles about the 1990s pursuit and capture of hacker Kevin Mitnick.

In computing, an avatar is a graphical representation of a user, the user's character, or persona. Avatars can be two-dimensional icons in Internet forums and other online communities, where they are also known as profile pictures, userpics, or formerly picons. Alternatively, an avatar can take the form of a three-dimensional model, as used in online worlds and video games, or an imaginary character with no graphical appearance, as in text-based games or worlds such as MUDs.

The Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society is a research center at Harvard University that focuses on the study of cyberspace. Founded at Harvard Law School, the center traditionally focused on internet-related legal issues. On May 15, 2008, the center was elevated to an interfaculty initiative of Harvard University as a whole. It is named after the Berkman family. On July 5, 2016, the center added "Klein" to its name following a gift of $15 million from Michael R. Klein.

"A Rape in Cyberspace, or How an Evil Clown, a Haitian Trickster Spirit, Two Wizards, and a Cast of Dozens Turned a Database into a Society" is an article written by freelance journalist Julian Dibbell and first published in The Village Voice in 1993. The article was later included in Dibbell's book My Tiny Life on his LambdaMOO experiences.

Fat Guy Stuck in Internet is an American science-fiction comedy television series created by John Gemberling and Curtis Gwinn for Cartoon Network's late-night adult-oriented programming block Adult Swim; and ended with a total of ten episodes.

Identity tourism may refer to the act of assuming a racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, sexual or gender identity for recreational purposes, or the construction of cultural identities and re-examination of one's ethnic and cultural heritage from what tourism offers its patrons.

Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace is a 1999 book by Lawrence Lessig on the structure and nature of regulation of the Internet.

Information technology law, also known as information, communication and technology law or cyberlaw, concerns the juridical regulation of information technology, its possibilities and the consequences of its use, including computing, software coding, artificial intelligence, the internet and virtual worlds. The ICT field of law comprises elements of various branches of law, originating under various acts or statutes of parliaments, the common and continental law and international law. Some important areas it covers are information and data, communication, and information technology, both software and hardware and technical communications technology, including coding and protocols.

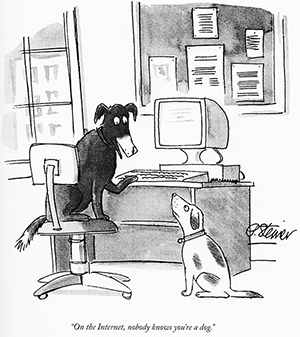

Peter Steiner is an American cartoonist, painter and novelist, best known for a 1993 cartoon published by The New Yorker which prompted the adage "On the Internet, nobody knows you're a dog." He is also a novelist who has published four crime novels.

I say it's spinach is a twentieth-century American idiom with the approximate meaning of "nonsense" or "rubbish". It is usually spoken or written as an anapodoton, thus only the first part of the complete phrase is given to imply the second part, which is what is actually meant: "I say the hell with it."