Related Research Articles

Islamic–Jewish relations comprise the human and diplomatic relations between Jewish people and Muslims in the Arabian Peninsula, Northern Africa, the Middle East, and their surrounding regions. Jewish–Islamic relations may also refer to the shared and disputed ideals between Judaism and Islam, which began roughly in the 7th century CE with the origin and spread of Islam in the Arabian peninsula. The two religions share similar values, guidelines, and principles. Islam also incorporates Jewish history as a part of its own. Muslims regard the Children of Israel as an important religious concept in Islam. Moses, the most important prophet of Judaism, is also considered a prophet and messenger in Islam. Moses is mentioned in the Quran more than any other individual, and his life is narrated and recounted more than that of any other prophet. There are approximately 43 references to the Israelites in the Quran, and many in the Hadith. Later rabbinic authorities and Jewish scholars such as Maimonides discussed the relationship between Islam and Jewish law. Maimonides himself, it has been argued, was influenced by Islamic legal thought.

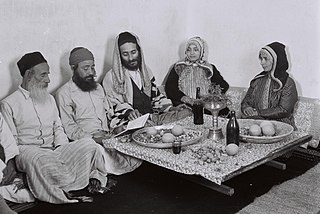

Yemenite Jews, also known as Yemeni Jews or Teimanim, are those Jews who live, or once lived, in Yemen, and their descendants maintaining their customs. Between June 1949 and September 1950, the overwhelming majority of the country's Jewish population immigrated to Israel in Operation Magic Carpet. After several waves of persecution, the vast majority of Yemenite Jews now live in Israel, while smaller communities live in the United States and elsewhere. As of 2022, only one Jew remained in Yemen.

Anusim is a legal category of Jews in halakha who were forced to abandon Judaism against their will, typically while forcibly converted to another religion. The term "anusim" is most properly translated as the "coerced [ones]" or the "forced [ones]".

Yahya Muhammad Hamid ed-Din became Imam of the Zaydis in 1904 after the death of his father, Muhammad Al-Mansur, and Imam of Yemen in 1918. His name and title in full was "His majesty Amir al-Mumenin al-Mutawakkil 'Ala Allah Rab ul-Alamin Imam Yahya bin al-Mansur Bi'llah Muhammad Hamidaddin, Imam and Commander of the Faithful".

African Jewish communities include:

The Dardaim or Dor Daim, are adherents of the Dor Deah movement in Orthodox Judaism. That movement took its name in 1912 in Yemen under Rabbi Yiḥyah Qafiḥ, and had its own network of synagogues and schools, although, in actuality, the movement existed long before that name had been coined for it. According to ethnographer and historian, Shelomo Dov Goitein, author and historiographer, Hayyim Habshush had been a member of this movement before it had been given the name Dor Deah, writing, “...He and his friends, partly under European influence, but driven mainly by developments among the Yemenite Jews themselves, formed a group who ardently opposed all those forces of mysticism, superstition and fatalism which were then so prevalent in the country and strove for exact knowledge and independent thought, and the application of both to life.” It was only some years later, when Rabbi Yihya Qafih became the headmaster of the new Jewish school in Sana'a built by the Ottoman Turks and where he wanted to introduce a new curriculum in the school whereby boys would also learn arithmetic and the rudiments of the Arabic and Turkish languages that Rabbi Yihya Yitzhak Halevi gave to Rabbi Qafih's movement the name Daradʻah, a word which is an Arabic broken plural made-up of the Hebrew words Dör Deʻoh, and which means "Generation of Knowledge."

Operation Magic Carpet is a widely known nickname for Operation On Wings of Eagles, an operation between June 1949 and September 1950 that brought 49,000 Yemenite Jews to the new state of Israel. During its course, the overwhelming majority of Yemenite Jews – some 47,000 from Yemen, 1,500 from Aden, as well as 500 from Djibouti and Eritrea and some 2,000 Jews from Saudi Arabia – were airlifted to Israel. British and American transport planes made some 380 flights from Aden.

Shalom Shabazi was the son of Yosef ben Avigad, of the family of Mashtā, also commonly known as Abba Sholem Shabazi or Saalem al-Shabazi. He was a Jewish poet who lived in 17th century Yemen, often referred to as the arch-poet of Yemen.

Forced conversion is the adoption of a religion or irreligion under duress. Someone who has been forced to convert to a different religion or irreligion may continue, covertly, to adhere to the beliefs and practices which were originally held, while outwardly behaving as a convert. Crypto-Jews, Crypto-Christians, Crypto-Muslims and Crypto-Pagans are historical examples of the latter.

Yiḥyah Qafiḥ (1850–1931), known also by his term of endearment "Ha-Yashish", served as the Chief Rabbi of Sana'a, Yemen in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He was one of the foremost rabbinical scholars in Sana'a during that period, and one who advocated many reforms in Jewish education. Besides being learned in astronomy and in the metaphysical science of rabbinic astrology, as well as in Jewish classical literature which he taught to his young students.

Judah ben Shalom, also known as Mori (Master) Shooker Kohail II or Shukr Kuhayl II, was a Yemenite messianic claimant of the mid-19th century.

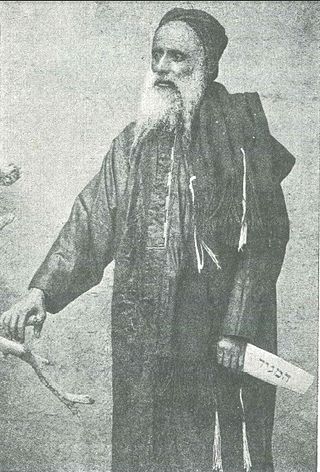

Shukr ben Salim Kuhayl I (?–1865), also known as Mari (Master) Shukr Kuhayl I, was a Yemenite messianic claimant of the 19th century. He initially revealed himself in San‘a’ in 1861 as a messenger of the Messiah at a time when Jewish messianic expectations in Ottoman Yemen were ripe as a result of political turmoil. Divorcing his wife, he took up the life of an itinerant preacher to live in poverty and exhort the community to repentance. "I come to warn you and to remind you of repentance and redemption," he is reported to have said when publicly announcing his mission on a Sabbath in May 1861.

Adeni Jews, or Adenite Jews are the historical Jewish community which resided in the port city of Aden. Adenite culture became distinct from other Yemenite Jewish culture due to British control of the city and Indian-Iraqi influence as well as recent arrivals from Persia and Egypt. Although they were separated, Adeni Jews depended on the greater Yemenite community for spiritual guidance, receiving their authorizations from Yemeni rabbis. Virtually the entire population emigrated from Aden between June 1947 and September 1967. As of 2004, there were 6,000 Adenites in Israel, and 1,500 in London.

This timeline of antisemitism chronicles events in the history of antisemitism, hostile actions or discrimination against Jews as members of a religious and/or ethnic group. It includes events in Jewish history and the history of antisemitic thought, actions which were undertaken in order to counter antisemitism or alleviate its effects, and events that affected the prevalence of antisemitism in later years. The history of antisemitism can be traced from ancient times to the present day.

The Habbani Jews are a culturally distinct Jewish population group from the Habban region in eastern Yemen, a subset of the larger ethnic group of Yemenite Jews. The city of Habban had a Jewish community of 450 in 1947, which was considered to possibly be the remains of a larger community which lived independently in the region before its decline in the 6th century. The Jewish community of Habban disappeared from the map of the Hadramaut, in southeast Yemen, with the emigration of all of its members to Israel in the 1950s.

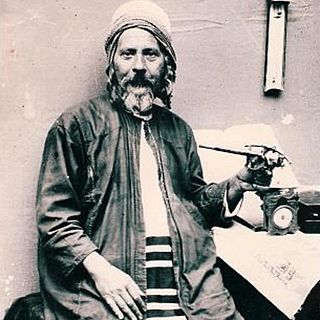

Rabbi Hayyim Habshush was a coppersmith by trade, and a noted nineteenth-century historiographer of Yemenite Jewry. He also served as a guide for the Jewish-French Orientalist and traveler Joseph Halévy. After his journey with Halévy in 1870, he was employed by Eduard Glaser and other later travellers to copy inscriptions and to collect old books.

The Mawza Exile is considered the single most traumatic event experienced collectively by the Jews of Yemen, in which Jews living in nearly all cities and towns throughout Yemen were banished by decree of the king, Imām al-Mahdi Ahmad, and sent to a dry and barren region of the country named Mawzaʻ to withstand their fate or to die. Only a few communities, viz., those Jewish inhabitants who lived in the far eastern quarters of Yemen were spared this fate by virtue of their Arab patrons who refused to obey the king's orders. Many would die along the route and while confined to the hot and arid conditions of this forbidding terrain. After one year in exile, the exiles were called back to perform their usual tasks and labors for the indigenous Arab populations, who had been deprived of goods and services on account of their exile.

Yemenite Jews in Israel are immigrants and descendants of the immigrants of the Yemenite Jewish communities, who now reside within the state of Israel. They number around 400,000 in the wider definition. Between June 1949 and September 1950, the overwhelming majority of Yemen and Aden's Jewish population was transported to Israel in Operation Magic Carpet.

Avraham Al-Naddaf (1866–1940), the son of Ḥayim b. Salem Al-Naddaf, was a Yemenite rabbi and scholar who immigrated to Ottoman Palestine in 1891, eventually becoming one of the members of the Yemenite rabbinical court (Beit-Din) established in Jerusalem in 1908, and active in public affairs. His maternal grandfather was Rabbi Yiḥya Badiḥi (1803–1887), the renowned sage and author of the Questions & Responsa, Ḥen Ṭov, and a commentary on the laws of ritual slaughter of livestock, Leḥem Todah, who served as the head of Sanaa's largest seat of learning (yeshiva), held in the synagogue, Bayt Saleḥ, before he was forced to flee from Sana'a in 1846 on account of the tyrant, Abū-Zayid b. Ḥasan al-Miṣrī, who persecuted the Jews under the Imam Al-Mutawakkil Muhammad.

Amram Qorah was the last Chief Rabbi in Yemen, assuming this role in 1934, after the death of Rabbi Yihya al-Abyadh, Resh Methivta, and which role he held for approximately two years. He is the author of the book, Sa'arat Teman, published post-mortem by the author's son, a book that documents the history of the Jews of Yemen and their culture for a little over 250 years, from the Mawza exile to the mass-immigration of Yemenite Jews to Israel in the mid-20th century.

References

- ↑ Bat-Zion Eraqi-Klorman (2001). "The forced conversion of Jewish orphans in Yemen". International Journal of Middle East Studies. Cambridge University Press. 33 (1): 23–47. JSTOR 259478.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Yehuda Nini (January 1, 1991). The Jews of the Yemen, 1800-1914. Routledge. pp. 21–23. ISBN 978-3-7186-5041-5.

- ↑ Simon, Reeva Spector; Laskier, Michael Menachem & Reguer, Sara, eds. (2003) The Jews of the Middle East and North Africa in Modern Times. New York: Columbia University Press; p. 392

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tudor Parfitt (October 6, 2000). Israel and Ishmael: studies in Muslim-Jewish relations. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 211–213. ISBN 978-0-312-22228-4.

- ↑ Yehiel Hibshush, Shənei Ha-me'oroth (שני המאורות), Tel-Aviv, 1987, pp. 10–11 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Rachel Yedid & Danny Bar-Maoz (ed.), Ascending the Palm Tree – An Anthology of the Yemenite Jewish Heritage, E'ele BeTamar: Rehovot 2018, p. 388 ISBN 978-965-7121-33-7; S. Dori, New Life [play], pub. in: From Yemen to Zion, Tel Aviv 1938, pp. 286–295