Related Research Articles

The New York City Transit Police Department was a law enforcement agency in New York City that existed from 1953 to 1995, and is currently part of the NYPD. The roots of this organization go back to 1936 when Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia authorized the hiring of special patrolmen for the New York City Subway. These patrolmen eventually became officers of the Transit Police. In 1949, the department was officially divorced from the New York City Police Department, but was eventually fully re-integrated in 1995 as the Transit Bureau of the New York City Police Department by New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani.

The New York City Police Department (NYPD), officially the City of New York Police Department, is the primary law enforcement agency within New York City. Established on May 23, 1845, the NYPD is the largest, and one of the oldest, municipal police departments in the United States.

David Norman Dinkins was an American politician, lawyer, and author who served as the 106th mayor of New York City from 1990 to 1993.

The Crown Heights riot was a race riot that took place from August 19 to August 21, 1991, in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, New York City. Black residents attacked Orthodox Jewish residents, damaged their homes, and looted businesses. The riots began on August 19, 1991, after two children of Guyanese immigrants were unintentionally struck by a driver running a red light while following the motorcade of Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the leader of Chabad, a Jewish religious movement. One child died and the second was severely injured.

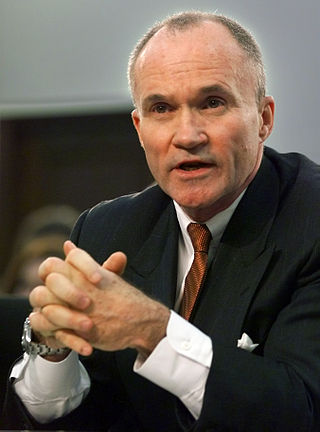

Raymond Walter Kelly is an American police officer who was the longest-serving Commissioner in the history of the New York City Police Department (NYPD) and the first person to hold the post for two non-consecutive tenures. According to its website, Kelly, a lifelong New Yorker, had spent 45 years in the NYPD, serving in 25 different commands and as Police Commissioner from 1992 to 1994 and again from 2002 until 2013. Kelly was the first man to rise from Police Cadet to Police Commissioner, holding all of the department's ranks, except for Three-Star Bureau Chief, Chief of Department and Deputy Commissioner, having been promoted directly from Two-Star Chief to First Deputy Commissioner in 1990. After his handling of the World Trade Center bombing in 1993, he was mentioned for the first time as a possible candidate for FBI Director. After Kelly turned down the position, Louis Freeh was appointed.

The Mollen Commission is formally known as The City of New York Commission to Investigate Allegations of Police Corruption and the Anti-Corruption Procedures of the Police Department. Former judge Milton Mollen was appointed in June 1992 by then New York City mayor David N. Dinkins to investigate corruption in the New York City Police Department. Mollen's mandate was to examine and investigate "the nature and extent of corruption in the Department; evaluate the department's procedures for preventing and detecting that corruption; and recommend changes and improvements to those procedures".

Crime rates in New York City have been recorded since at least the 1800s, with varying levels of precision. The highest crime totals were recorded in the late 1980s and early 1990s as the crack epidemic surged, and then declined continuously since the mid-1990s and throughout the 2000s. A smaller spike occurred during and after the Covid pandemic, but today, New York City has significantly lower rates of violent crime than many other large cities. Its 2022 homicide rate of 6.0 per 100,000 residents compares favorably to the rate in the United States as a whole and to rates in much more violent cities such as St. Louis and New Orleans.

The Tompkins Square Park riot occurred on August 6–7, 1988 in Tompkins Square Park, located in the East Village and Alphabet City neighborhoods of Manhattan, New York City. Groups of "drug pushers, homeless people and young people known as squatters and punks," had largely taken over the park. The East Village and Alphabet City communities were divided about what, if anything, should be done about it. The local governing body, Manhattan Community Board 3, recommended, and the New York City Parks Department adopted a 1 a.m. curfew for the previously 24-hour park, in an attempt to bring it under control. On July 31, a protest rally against the curfew saw several clashes between protesters and police.

The NYC Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB) is a civilian oversight agency with jurisdiction over the New York City Police Department (NYPD), the largest police force in the United States. A board of the Government of New York City, the CCRB is tasked with investigating, mediating and prosecuting complaints of misconduct on the part of the NYPD. Its regulations are compiled in Title 38-A of the New York City Rules.

The Police Benevolent Association of the City of New York (PBA) is the largest police union representing police officers of the New York City Police Department. It represents about 24,000 of the department's 36,000 officers.

The Harlem riot of 1964 occurred between July 16 and 22, 1964. It began after James Powell, a 15-year-old African American, was shot and killed by police Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan in front of Powell's friends and about a dozen other witnesses. Hundreds of students from Powell's school protested the killing. The shooting set off six consecutive nights of rioting that affected the New York City neighborhoods of Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant. By some accounts, 4,000 people participated in the riots. People attacked the New York City Police Department (NYPD), destroyed property, and looted stores. Several protesters were severely beaten by NYPD officers. The riots and unrest left one dead, 118 injured, and 465 arrested.

The New York City Police Department (NYPD) originates in the Government of New York City attempts to control rising crime in early- to mid-19th-century New York City. The City's reforms created a full-time professional police force modeled upon London's Metropolitan Police, itself only formed in 1829. Established in 1845, the Municipal Police replaced the inadequate night watch system which had been in place since the 17th century, when the city was founded by the Dutch as New Amsterdam.

Throughout the history of the New York City Police Department, numerous instances of corruption, misconduct, and other allegations of such, have occurred. Over 12,000 cases have resulted in lawsuit settlements totaling over $400 million during a five-year period ending in 2014. In 2019, misconduct lawsuits cost the taxpayer $68,688,423, a 76 percent increase over the previous year, including about $10 million paid out to two exonerated individuals who had been falsely convicted and imprisoned.

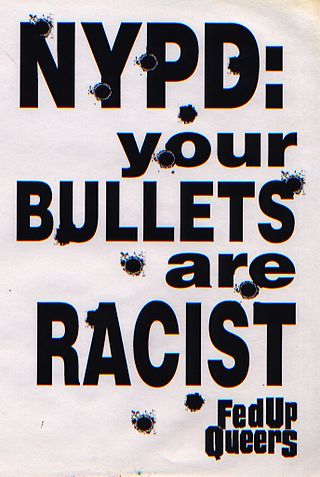

Fed Up Queers, or FUQ, was a queer activist direct action group that began in New York City. The group was made up mostly of lesbians such as Jennifer Flynn, though notable participants also included gay rights pioneer and Stonewall riots veteran Bob Kohler, and writer Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore. The activists who formed FUQ came together loosely for a few actions in 1998, but the first action attributed to Fed Up Queers was on World AIDS Day, December 1, 1998, when they visited New York State Assemblywoman Nettie Mayersohn's house in Queens at midnight to protest her stance on names reporting.

The 1993 New York City mayoral election was held on Tuesday, November 2. Incumbent Mayor David Dinkins ran for re-election to a second term, but lost in a rematch with Republican Rudy Giuliani.

Patrick J. Lynch is a New York City Police Department officer, and the former president of its union, the Police Benevolent Association of the City of New York, which he has served for six consecutive terms in office. He retired as union president at the end of June 2023.

100 Blacks In Law Enforcement That Care is an American New York City-based advocacy group which focuses on fighting injustices between the African American community and their interactions with the New York City Police Department (NYPD). This internal relations advocacy group speaks out against police brutality, racial profiling and police misconduct. They are composed of active duty and retired employees from within the department. They also support the black community with financial, educational and legal support.

George Floyd protests in New York City took place at several sites in each of the five New York City boroughs, starting on May 28, 2020, in reaction to the murder of George Floyd. Most of the protests were peaceful, while some sites experienced protester and/or police violence, including several high-profile incidents of excessive force. Looting became a parallel issue, especially in Manhattan. As a result, and amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the city was placed under curfew from June 1–7, the first curfew in the city since 1943. The protests catalyzed efforts at police reform, leading to the criminalization of chokeholds during arrests, the repeal of 50-a, and other legislation. Several murals and memorials were created around the city in George Floyd's honor, and demonstrations against racial violence and police brutality continued as part of the larger Black Lives Matter movement in New York City.

Michael Joseph Codd was an American law enforcement officer who served as New York City Police Commissioner from 1974 to 1977.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Shielded from Justice: New York: Civilian Complaint Review Board". www.hrw.org. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

- ↑ "Police Unions Haven't Only Battled Bill de Blasio's City Hall". Observer. 2014-12-22. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

- ↑ Oliver, Pamela (18 July 2020). "When the NYPD Rioted – Race, Politics, Justice" . Retrieved 2021-01-15.

- ↑ Voorhees, Josh (2014-12-22). "Déjà Blue". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339 . Retrieved 2016-11-29.

- ↑ Manegold, Catherine S. (1992-09-27). "Rally Puts Police Under New Scrutiny". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved 2020-06-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Mckinley, James C. Jr. (1992-09-17). "Officers Rally And Dinkins Is Their Target". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved 2016-11-29.

- ↑ James, George (1992-09-29). "Police Dept. Report Assails Officers in New York Rally (Published 1992)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved 2021-01-15.

- ↑ Donovan, Kenneth (July 28, 2020). "Police and Protest: 1992 and Today". Gotham Gazette. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Nahmias, Laura (October 4, 2021). "White Riot In 1992, thousands of furious, drunken cops descended on City Hall — and changed New York history". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ↑ Finder, Alan (September 11, 1992). "The Washington Heights Case; In Washington Heights, Dinkins Defends Actions After Shooting". The New York Times. Retrieved January 21, 2022.