The king cobra is a venomous snake endemic to Asia. The sole member of the genus Ophiophagus, it is not taxonomically a true cobra, despite its common name and some resemblance. With an average length of 3.18 to 4 m and a record length of 5.85 m (19.2 ft), it is the world's longest venomous snake. The species has diversified colouration across habitats, from black with white stripes to unbroken brownish grey. The king cobra is widely distributed albeit not commonly seen, with a range spanning from the Indian Subcontinent through Southeastern Asia to Southern China. It preys chiefly on other snakes, including those of its own kind. This is the only ophidian that constructs an above-ground nest for its eggs, which are purposefully and meticulously gathered and protected by the female throughout the incubation period.

A snakebite is an injury caused by the bite of a snake, especially a venomous snake. A common sign of a bite from a venomous snake is the presence of two puncture wounds from the animal's fangs. Sometimes venom injection from the bite may occur. This may result in redness, swelling, and severe pain at the area, which may take up to an hour to appear. Vomiting, blurred vision, tingling of the limbs, and sweating may result. Most bites are on the hands, arms, or legs. Fear following a bite is common with symptoms of a racing heart and feeling faint. The venom may cause bleeding, kidney failure, a severe allergic reaction, tissue death around the bite, or breathing problems. Bites may result in the loss of a limb or other chronic problems or even death.

Snake venom is a highly toxic saliva containing zootoxins that facilitates in the immobilization and digestion of prey. This also provides defense against threats. Snake venom is injected by unique fangs during a bite, whereas some species are also able to spit venom.

The banded krait is a species of elapids endemic to Asia, from Indian Subcontinent through Southeast Asia to Southern China. With a maximum length exceeding 2 m, it is the longest krait with a distinguishable gold and black pattern. While this species is generally considered timid and docile, resembling other members of the genus, its venom is highly neurotoxic which is potentially lethal to humans. Although toxicity of the banded krait based upon murine LD50 experiments is lower than that of many other kraits, its venom yield is the highest due to its size.

Bitis nasicornis is a viper species belonging to the genus Bitis, part of a subfamily known as "puff-adders", found in the forests of West and Central Africa. This large viper is known for its striking coloration and prominent nasal "horns". No subspecies are currently recognized. Its common names include butterfly viper, rhinoceros viper, river jack and many more. Like all other vipers, it is venomous.

The four venomous snake species responsible for causing the greatest number of medically significant human snake bite cases on the Indian subcontinent are sometimes collectively referred to as the Big Four. They are as follows:

- Russell's viper, Daboia russelii

- Common krait, Bungarus caeruleus

- Indian cobra, Naja naja

- Indian saw-scaled viper, Echis carinatus

The Caspian cobra, also called the Central Asian cobra, ladle snake, Oxus cobra, or Russian cobra, is a species of highly venomous snake in the family Elapidae. The species is endemic to Central Asia. Described by Karl Eichwald in 1831, it was for many years considered a subspecies of the Indian cobra until genetic analysis revealed it to be a distinct species.

Hydrophis schistosus, commonly known as the beaked sea snake, hook-nosed sea snake, common sea snake, or the Valakadeyan sea snake, is a highly venomous species of sea snake common throughout the tropical Indo-Pacific. This species is implicated in more than 50% of all bites caused by sea snakes, as well as the majority of envenomings and fatalities.

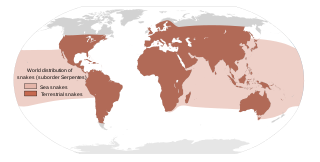

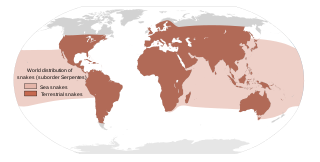

Venomous snakes are species of the suborder Serpentes that are capable of producing venom, which they use for killing prey, for defense, and to assist with digestion of their prey. The venom is typically delivered by injection using hollow or grooved fangs, although some venomous snakes lack well-developed fangs. Common venomous snakes include the families Elapidae, Viperidae, Atractaspididae, and some of the Colubridae. The toxicity of venom is mainly indicated by murine LD50, while multiple factors are considered to judge the potential danger to humans. Other important factors for risk assessment include the likelihood that a snake will bite, the quantity of venom delivered with the bite, the efficiency of the delivery mechanism, and the location of a bite on the body of the victim. Snake venom may have both neurotoxic and hemotoxic properties. There are about 600 venomous snake species in the world.

Echis is a genus of vipers found in the dry regions of Africa, the Middle East, India, Sri Lanka and Pakistan. They have a characteristic threat display, rubbing sections of their body together to produce a "sizzling" warning sound. The name Echis is the Latin transliteration of the Greek word for "viper" (ἔχις). Like all vipers, they are venomous. Their common name is "saw-scaled vipers" and they include some of the species responsible for causing the most snakebite cases and deaths in the world. Twelve species are currently recognized.

Vipera is a genus of vipers. It has a very wide range, being found from North Africa to just within the Arctic Circle and from Great Britain to Pacific Asia. The Latin name vīpera is possibly derived from the Latin words vivus and pario, meaning "alive" and "bear" or "bring forth"; likely a reference to the fact that most vipers bear live young. Currently, 21 species are recognized. Like all other vipers, the members of this genus are venomous.

Vipera ammodytes, commonly known as horned viper, long-nosed viper, nose-horned viper, and sand viper, poskok is a species of viper found in southern Europe, mainly northern Italy, the Balkans, and parts of Asia Minor. Like all other vipers, it is venomous. It is reputed to be the most dangerous of the European vipers due to its large size, long fangs and high venom toxicity. The specific name, ammodytes, is derived from the Greek words ammos, meaning "sand", and dutes, meaning "burrower" or "diver", despite its preference for rocky habitats. Five subspecies are currently recognized, including the nominate subspecies described here.

Naja is a genus of venomous elapid snakes commonly known as cobras. Members of the genus Naja are the most widespread and the most widely recognized as "true" cobras. Various species occur in regions throughout Africa, Southwest Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Several other elapid species are also called "cobras", such as the king cobra and the rinkhals, but neither is a true cobra, in that they do not belong to the genus Naja, but instead each belong to monotypic genera Hemachatus and Ophiophagus.

Vipera aspis is a viper species found in southwestern Europe. Its common names include asp, asp viper, European asp, and aspic viper, among others. Like all other vipers, it is venomous. Bites from this species can be more severe than from the European adder, V. berus; not only can they be very painful, but approximately 4% of all untreated bites are fatal. The specific epithet, aspis, is a Greek word that means "viper." Five subspecies are currently recognized, including the nominate subspecies described here.

Daboia siamensis is a venomous viper species, which is endemic to parts of Southeast Asia, southern China and Taiwan. It was formerly considered to be a subspecies of Daboia russelii, but was elevated to species status in 2007.

The horned adder is a viper species. It is found in the arid region of southwest Africa, in Angola, Botswana, Namibia; South Africa, and Zimbabwe. It is easily distinguished by the presence of a single, large horn-like scale over each eye. No subspecies are currently recognized. Like all other vipers, it is venomous.

Montivipera xanthina, known as the rock viper, coastal viper, Ottoman viper, and by other common names, is a viper species found in northeastern Greece and Turkey, as well as certain islands in the Aegean Sea. Like all other vipers, it is venomous. No subspecies are currently recognized.

Most snakebites are caused by non-venomous snakes. Of the roughly 3,700 known species of snake found worldwide, only 15% are considered dangerous to humans. Snakes are found on every continent except Antarctica. There are two major families of venomous snakes, Elapidae and Viperidae. 325 species in 61 genera are recognized in the family Elapidae and 224 species in 22 genera are recognized in the family Viperidae, In addition, the most diverse and widely distributed snake family, the colubrids, has approximately 700 venomous species, but only five genera—boomslangs, twig snakes, keelback snakes, green snakes, and slender snakes—have caused human fatalities.

Daboia is a genus of venomous vipers.