Related Research Articles

Tourette syndrome or Tourette's syndrome is a common neurodevelopmental disorder that begins in childhood or adolescence. It is characterized by multiple movement (motor) tics and at least one vocal (phonic) tic. Common tics are blinking, coughing, throat clearing, sniffing, and facial movements. These are typically preceded by an unwanted urge or sensation in the affected muscles known as a premonitory urge, can sometimes be suppressed temporarily, and characteristically change in location, strength, and frequency. Tourette's is at the more severe end of a spectrum of tic disorders. The tics often go unnoticed by casual observers.

Coprolalia is involuntary swearing or the involuntary utterance of obscene words or socially inappropriate and derogatory remarks. The word comes from the Greek κόπρος, meaning "dung, feces", and λαλιά "speech", from λαλεῖν "to talk".

A tic is a sudden and repetitive motor movement or vocalization that is not rhythmic and involves discrete muscle groups. It is typically brief, and may resemble a normal behavioral characteristic or gesture.

Excoriation disorder, more commonly known as dermatillomania, is a mental disorder on the obsessive–compulsive spectrum that is characterized by the repeated urge or impulse to pick at one's own skin, to the extent that either psychological or physical damage is caused.

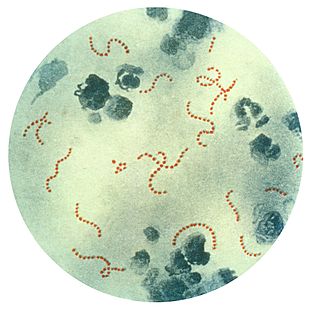

Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS) is a controversial hypothetical diagnosis for a subset of children with rapid onset of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or tic disorders. Symptoms are proposed to be caused by group A streptococcal (GAS), and more specifically, group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal (GABHS) infections. OCD and tic disorders are hypothesized to arise in a subset of children as a result of a post-streptococcal autoimmune process. The proposed link between infection and these disorders is that an autoimmune reaction to infection produces antibodies that interfere with basal ganglia function, causing symptom exacerbations, and this autoimmune response results in a broad range of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Tic disorders are defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) based on type and duration of tics. Tic disorders are defined similarly by the World Health Organization.

Tourette syndrome is an inherited neurodevelopmental disorder that begins in childhood or adolescence, characterized by the presence of motor and phonic tics. The management of Tourette syndrome has the goal of managing symptoms to achieve optimum functioning, rather than eliminating symptoms; not all persons with Tourette's require treatment, and there is no cure or universally effective medication. Explanation and reassurance alone are often sufficient treatment; education is an important part of any treatment plan.

Causes and origins of Tourette syndrome have not been fully elucidated. Tourette syndrome is an inherited neurodevelopmental disorder that begins in childhood or adolescence, characterized by the presence of multiple motor tics and at least one phonic tic, which characteristically wax and wane. Tourette's syndrome occurs along a spectrum of tic disorders, which includes transient tics and chronic tics.

The Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) is a test to rate the severity of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) symptoms.

The obsessive–compulsive spectrum is a model of medical classification where various psychiatric, neurological and/or medical conditions are described as existing on a spectrum of conditions related to obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD). "The disorders are thought to lie on a spectrum from impulsive to compulsive where impulsivity is said to persist due to deficits in the ability to inhibit repetitive behavior with known negative consequences, while compulsivity persists as a consequence of deficits in recognizing completion of tasks." OCD is a mental disorder characterized by obsessions and/or compulsions. An obsession is defined as "a recurring thought, image, or urge that the individual cannot control". Compulsion can be described as a "ritualistic behavior that the person feels compelled to perform". The model suggests that many conditions overlap with OCD in symptomatic profile, demographics, family history, neurobiology, comorbidity, clinical course and response to various pharmacotherapies. Conditions described as being on the spectrum are sometimes referred to as obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders.

Tourette syndrome is an inherited neurological disorder that begins in childhood or adolescence, characterized by the presence of multiple physical (motor) tics and at least one vocal (phonic) tic.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder management options are evidence-based practices with established treatment efficacy for ADHD.

The Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), developed and popularised by Robert Young and Vincent E Ziegler, is an eleven-item multiple choice diagnostic questionnaire which psychiatrists use to measure the presence and severity of mania and associated symptoms. The scale was originally developed for use in the evaluation of adult patients with bipolar disorder, but has since been adapted for use in pediatric patients. The scale is widely used by clinicians and researchers in the diagnosis, evaluation, and quantification of manic symptomology. It has become the most widely used outcome measure in clinical trials for bipolar disorders, and it is recognized by many regulatory agencies as an acceptable outcome measure despite its age.

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is a mental and behavioral disorder in which an individual has intrusive thoughts and feels the need to perform certain routines (compulsions) repeatedly to relieve the distress caused by the obsession, to the extent where it impairs general function.

A depression rating scale is a psychometric instrument (tool), usually a questionnaire whose wording has been validated with experimental evidence, having descriptive words and phrases that indicate the severity of depression for a time period. When used, an observer may make judgements and rate a person at a specified scale level with respect to identified characteristics. Rather than being used to diagnose depression, a depression rating scale may be used to assign a score to a person's behaviour where that score may be used to determine whether that person should be evaluated more thoroughly for a depressive disorder diagnosis. Several rating scales are used for this purpose.

The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) is a psychological measure designed to assess the severity and frequency of symptoms of disorders such as tic disorder, Tourette syndrome, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, in children and adolescents between ages 6 and 17.

The Child Mania Rating Scales (CMRS) is a 21-item diagnostic screening measure designed to identify symptoms of mania in children and adolescents aged 9–17 using diagnostic criteria from the DSM-IV, developed by Pavuluri and colleagues. There is also a 10-item short form. The measure assesses the child's mood and behavior symptoms, asking parents or teachers to rate how often the symptoms have caused a problem for the youth in the past month. Clinical studies have found the CMRS to be reliable and valid when completed by parents in the assessment of children's bipolar symptoms. The CMRS also can differentiate cases of pediatric bipolar disorder from those with ADHD or no disorder, as well as delineating bipolar subtypes. A meta-analysis comparing the different rating scales available found that the CMRS was one of the best performing scales in terms of telling cases with bipolar disorder apart from other clinical diagnoses. The CMRS has also been found to provide a reliable and valid assessment of symptoms longitudinally over the course of treatment. The combination of showing good reliability and validity across multiple samples and clinical settings, along with being free and brief to score, make the CMRS a promising tool, especially since most other checklists available for youths do not assess manic symptoms.

The Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DOCS) is a 20-item self-report instrument that assesses the severity of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) symptoms along four empirically supported theme-based dimensions: (a) contamination, (b) responsibility for harm and mistakes, (c) incompleteness/symmetry, and (d) unacceptable (taboo) thoughts. The scale was developed in 2010 by a team of experts on OCD led by Jonathan Abramowitz, PhD to improve upon existing OCD measures and advance the assessment and understanding of OCD. The DOCS contains four subscales that have been shown to have good reliability, validity, diagnostic sensitivity, and sensitivity to treatment effects in a variety of settings cross-culturally and in different languages. As such, the DOCS meets the needs of clinicians and researchers who wish to measure current OCD symptoms or assess changes in symptoms over time.

The Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory (CASI) is a behavioral rating checklist created by Kenneth Gadow and Joyce Sprafkin that evaluates a range of behaviors related to common emotional and behavioral disorders identified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, separation anxiety disorder, major depressive episode, mania, dysthymic disorder, schizophrenia, autism spectrum, Asperger syndrome, anorexia, and bulimia. In addition, one or two key symptoms from each of the following disorders are also included: obsessive-compulsive disorder, specific phobia, panic attack, motor/vocal tics, and substance use. CASI combines the Child Symptom Inventory (CSI) and the Adolescent Symptom Inventory (ASI), letting it apply to both children and adolescents, aged from 5 to 18. The CASI is a self-report questionnaire completed by the child's caretaker or teacher to detect signs of psychiatric disorders in multiple settings. Compared to other widely used checklists for youths, the CASI maps more closely to DSM diagnoses, with scoring systems that map to the diagnostic criteria as well as providing a severity score. Other measures are more likely to have used statistical methods, such as factor analysis, to group symptoms that often occur together; if they have DSM-oriented scales, they are often later additions that only include some of the diagnostic criteria.

The Autism – Tics, AD/HD, and other Comorbidities (A–TAC) is a psychological measure used to screen for other conditions occurring with tics. Along with tic disorders, it screens for autism spectrum disorders, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and other conditions with onset in childhood. The A-TAC has been reported as valid and reliable for detecting most disorders in children. One telephone survey found it was not validated for eating disorders.

References

- ↑ Müller, Norbert (2007-06-30). "Tourette's syndrome: clinical features, pathophysiology, and therapeutic approaches". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 9 (2): 161–171. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2007.9.2/nmueller. ISSN 1958-5969. PMC 3181853 . PMID 17726915.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Shytle, R. Douglas; Silver, Archie A.; Sheehan, Kathy Harnett; Wilkinson, Berney J.; Newman, Mary; Sanberg, Paul R.; Sheehan, David (September 2003). "The Tourette's Disorder Scale (TODS): Development, Reliability, and Validity". Assessment. 10 (3): 273–287. doi:10.1177/1073191103255497. ISSN 1073-1911. PMID 14503651.

- ↑ Haas, Martina; Jakubovski, Ewgeni; Fremer, Carolin; Dietrich, Andrea; Hoekstra, Pieter J.; Jäger, Burkard; Müller-Vahl, Kirsten R.; The EMTICS Collaborative Group (2021-02-25). "Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS): Psychometric Quality of the Gold Standard for Tic Assessment Based on the Large-Scale EMTICS Study". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.626459 . ISSN 1664-0640. PMC 7949908 . PMID 33716826.

- 1 2 3 4 Martino, Davide; Pringsheim, Tamara M.; Cavanna, Andrea E.; Colosimo, Carlo; Hartmann, Andreas; Leckman, James F.; Luo, Sheng; Munchau, Alexander; Goetz, Christopher G.; Stebbins, Glenn T.; Martinez-Martin, Pablo; the Members of the MDS Committee on Rating Scales Development (March 2017). "Systematic review of severity scales and screening instruments for tics: Critique and recommendations". Movement Disorders. 32 (3): 467–473. doi:10.1002/mds.26891. ISSN 0885-3185. PMC 5482361 . PMID 28071825.

- ↑ Gadow, Kenneth D. (1991). "Clinical issues in child and adolescent psychopharmacology". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 59 (6): 842–852. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.59.6.842. ISSN 0022-006X. PMID 1774369.

- ↑ Poulter, Caroline; Mills, Jonathan (July 2018). "Tourette's syndrome and tic disorders". InnovAiT: Education and Inspiration for General Practice. 11 (7): 362–365. doi:10.1177/1755738017740914. ISSN 1755-7380.

- ↑ Valderas, J. M.; Starfield, B.; Sibbald, B.; Salisbury, C.; Roland, M. (2009-07-01). "Defining Comorbidity: Implications for Understanding Health and Health Services". The Annals of Family Medicine. 7 (4): 357–363. doi:10.1370/afm.983. ISSN 1544-1709. PMC 2713155 . PMID 19597174.

- 1 2 Kumar, Ashutosh; Trescher, William; Byler, Debra (December 2016). "Tourette Syndrome and Comorbid Neuropsychiatric Conditions". Current Developmental Disorders Reports. 3 (4): 217–221. doi:10.1007/s40474-016-0099-1. ISSN 2196-2987. PMC 5104764 . PMID 27891299.

- ↑ Robertson, Mary May (May 2016). "Tourette syndrome in children and adolescents: aetiology, presentation and treatment". BJPsych Advances. 22 (3): 165–175. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.114.014092. ISSN 2056-4678.

- ↑ Rizzo, Renata; Gulisano, Mariangela; Calì, Paola Valeria; Curatolo, Paolo (September 2012). "Long term clinical course of Tourette syndrome". Brain and Development. 34 (8): 667–673. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2011.11.006. PMID 22178151.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Storch, Eric A.; Merlo, Lisa J.; Lehmkuhl, Heather; Grabill, Kristen M.; Geffken, Gary R.; Goodman, Wayne K.; Murphy, Tanya K. (August 2007). "Further Psychometric Examination of the Tourette's Disorder Scales". Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 38 (2): 89–98. doi:10.1007/s10578-006-0043-4. ISSN 0009-398X. PMID 17136450.

- 1 2 3 Eapen, Valsamma; Robertson, Mary M. (2008-04-15). "Clinical Correlates of Tourette's Disorder Across Cultures: A Comparative Study Between the United Arab Emirates and the United Kingdom". The Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 10 (2): 103–107. doi:10.4088/PCC.v10n0203. ISSN 1523-5998. PMC 2292447 . PMID 18458733.