The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits the United States and its states from denying the right to vote to citizens of the United States on the basis of sex, in effect recognizing the right of women to vote. The amendment was the culmination of a decades-long movement for women's suffrage in the United States, at both the state and national levels, and was part of the worldwide movement towards women's suffrage and part of the wider women's rights movement. The first women's suffrage amendment was introduced in Congress in 1878. However, a suffrage amendment did not pass the House of Representatives until May 21, 1919, which was quickly followed by the Senate, on June 4, 1919. It was then submitted to the states for ratification, achieving the requisite 36 ratifications to secure adoption, and thereby go into effect, on August 18, 1920. The Nineteenth Amendment's adoption was certified on August 26, 1920.

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Its membership, which was about seven thousand at the time it was formed, eventually increased to two million, making it the largest voluntary organization in the nation. It played a pivotal role in the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which in 1920 guaranteed women's right to vote.

The Republican Party of New Mexico is the affiliate of the United States Republican Party in New Mexico. It is headquartered in Albuquerque and led by Chair Steve Pearce, Vice Chair Frank Trambley, Secretary Mari Trujillo Spinelli, and Treasurer David Chavez.

The 1916 Democratic National Convention was held at the St. Louis Coliseum in St. Louis, Missouri from June 14 to June 16, 1916. It resulted in the nomination of President Woodrow Wilson and Vice President Thomas R. Marshall for reelection.

María Adelina Isabel Emilia "Nina" Otero-Warren was an American woman's suffragist, educator, and politician. Otero-Warren created a legacy of civil service through her work in education, politics, and public health. She became one of New Mexico's first female government officials when she served as Santa Fe Superintendent of Instruction from 1917 to 1929. Otero-Warren was the first Latina to run for Congress, running unsuccessfully in 1922 as the Republican nominee to represent New Mexico's at-large district in the U.S. House of Representatives.

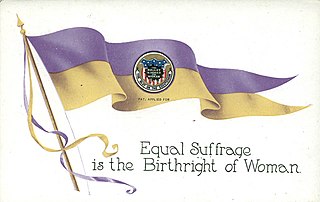

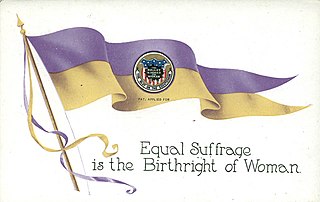

This timeline highlights milestones in women's suffrage in the United States, particularly the right of women to vote in elections at federal and state levels.

Women's suffrage was established in the United States on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a member of Congress.

Julia Duncan Brown Asplund (1875-1958) was the first librarian for the University of New Mexico and the first woman to serve on the University of New Mexico Board of Regents.

Aurora Lucero-White Lea was an American folklorist, writer, and suffragist. She was a proud Nuevomexicana, advocating for bilingual education in English and Spanish and working to preserve the heritage of the Hispanic Southwest. Lucero-White Lea is best known for her 1953 work Literary Folklore of the Hispanic Southwest, a compilation of cultural traditions, songs, and stories collected while traveling northern New Mexico.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in New Mexico. Women's suffrage in New Mexico first began with granting women the right to vote in school board elections and was codified into the New Mexico State Constitution, written in 1910. In 1912, New Mexico was a state, and suffragists there worked to support the adoption of a federal women's suffrage amendment to allow women equal suffrage. Even after white women earned the right to vote in 1920, many Native Americans were unable to vote in the state.

The women's suffrage movement was active in Missouri mostly after the Civil War. There were significant developments in the St. Louis area, though groups and organized activity took place throughout the state. An early suffrage group, the Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri, was formed in 1867, attracting the attention of Susan B. Anthony and leading to news items around the state. This group, the first of its kind, lobbied the Missouri General Assembly for women's suffrage and established conventions. In the early 1870s, many women voted or registered to vote as an act of civil disobedience. The suffragist Virginia Minor was one of these women when she tried to register to vote on October 15, 1872. She and her husband, Francis Minor, sued, leading to a Supreme Court case that asserted the Fourteenth Amendment granted women the right to vote. The case, Minor v. Happersett, was decided against the Minors and led suffragists in the country to pursue legislative means to grant women suffrage.

The women's suffrage movement in Montana started while it was still a territory. The Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was an early organizer that supported suffrage in the state, arriving in 1883. Women were given the right to vote in school board elections and on tax issues in 1887. When the state constitutional convention was held in 1889, Clara McAdow and Perry McAdow invited suffragist Henry Blackwell to speak to the delegates about equal women's suffrage. While that proposition did not pass, women retained their right to vote in school and tax elections as Montana became a state. In 1895, National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) came to Montana to organize local groups. Montana suffragists held a convention and created the Montana Woman's Suffrage Association (MWSA). Suffragists continued to organize, hold conventions and lobby the Montana Legislature for women's suffrage through the end of the nineteenth century. In the early twentieth century, Jeannette Rankin became a driving force around the women's suffrage movement in Montana. By January 1913, a women's suffrage bill had passed the Montana Legislature and went out as a referendum. Suffragists launched an all-out campaign leading up to the vote. They traveled throughout Montana giving speeches and holding rallies. They sent out thousands of letters and printed thousands of pamphlets and journals to hand out. Suffragists set up booths at the Montana State Fair and they held parades. Finally, after a somewhat contested election on November 3, 1914, the suffragists won the vote. Montana became one of eleven states with equal suffrage for most women. When the Nineteenth Amendment was passed, Montana ratified it on August 2, 1919. It wasn't until 1924 with the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act that Native American women gained the right to vote.

The first women's suffrage group in Georgia, the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA), was formed in 1892 by Helen Augusta Howard. Over time, the group, which focused on "taxation without representation" grew and earned the support of both men and women. Howard convinced the National American Women's Suffrage Association (NAWSA) to hold their first convention outside of Washington, D.C., in 1895. The convention, held in Atlanta, was the first large women's rights gathering in the Southern United States. GWSA continued to hold conventions and raise awareness over the next years. Suffragists in Georgia agitated for suffrage amendments, for political parties to support white women's suffrage and for municipal suffrage. In the 1910s, more organizations were formed in Georgia and the number of suffragists grew. In addition, the Georgia Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage also formed an organized anti-suffrage campaign. Suffragists participated in parades, supported bills in the legislature and helped in the war effort during World War I. In 1917 and 1919, women earned the right to vote in primary elections in Waycross, Georgia and in Atlanta respectively. In 1919, after the Nineteenth Amendment went out to the states for ratification, Georgia became the first state to reject the amendment. When the Nineteenth Amendment became the law of the land, women still had to wait to vote because of rules regarding voter registration. White Georgia women would vote statewide in 1922. Native American women and African-American women had to wait longer to vote. Black women were actively excluded from the women's suffrage movement in the state and had their own organizations. Despite their work to vote, Black women faced discrimination at the polls in many different forms. Georgia finally ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on February 20, 1970.

Women's suffrage began in Delaware the late 1860s, with efforts from suffragist, Mary Ann Sorden Stuart, and an 1869 women's rights convention held in Wilmington, Delaware. Stuart, along with prominent national suffragists lobbied the Delaware General Assembly to amend the state constitution in favor of women's suffrage. Several suffrage groups were formed early on, but the Delaware Equal Suffrage Association (DESA) formed in 1896, would become one of the major state suffrage clubs. Suffragists held conventions, continued to lobby the government and grow their movement. In 1913, a chapter of the Congressional Union (CU), which would later be known at the National Woman's Party (NWP), was set up by Mabel Vernon in Delaware. NWP advocated more militant tactics to agitate for women's suffrage. These included picketing and setting watchfires. The Silent Sentinels protested in Washington, D.C., and were arrested for "blocking traffic." Sixteen women from Delaware, including Annie Arniel and Florence Bayard Hilles, were among those who were arrested. During World War I, both African-American and white suffragists in Delaware aided the war effort. During the ratification process for the Nineteenth Amendment, Delaware was in the position to become the final state needed to complete ratification. A huge effort went into persuading the General Assembly to support the amendment. Suffragists and anti-suffragists alike campaigned in Dover, Delaware for their cause. However, Delaware did not ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until March 6, 1923, well after it was already part of the United States Constitution.

The movement for women's suffrage in Arizona began in the late 1800s. After women's suffrage was narrowly voted down at the 1891 Arizona Constitutional Convention, prominent suffragettes such as Josephine Brawley Hughes and Laura M. Johns formed the Arizona Suffrage Association and began touring the state campaigning for women's right to vote. Momentum built throughout the decade, and after a strenuous campaign in 1903, a woman's suffrage bill passed both houses of the legislature but was ultimately vetoed by Governor Alexander Oswald Brodie.

Women's suffrage had early champions among men in Arkansas. Miles Ledford Langley of Arkadelphia, Arkansas proposed a women's suffrage clause during the 1868 Arkansas Constitutional Convention. Educator, James Mitchell wanted to see a world where his daughters had equal rights. The first woman's suffrage group in Arkansas was organized by Lizzie Dorman Fyler in 1881. A second women's suffrage organization was formed by Clara McDiarmid in 1888. McDiarmid was very influential on women's suffrage work in the last few decades of the nineteenth century. When she died in 1899, suffrage work slowed down, but did not all-together end. Both Bernie Babcock and Jean Vernor Jennings continued to work behind the scenes. In the 1910s, women's suffrage work began to increase again. socialist women, like Freda Hogan were very involved in women's suffrage causes. Other social activists, like Minnie Rutherford Fuller became involved in the Political Equality League (PEL) founded in 1911 by Jennings. Another statewide suffrage group, also known as the Arkansas Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) was organized in 1914. AWSA decided to work towards helping women vote in the important primary elections in the state. The first woman to address the Arkansas General Assembly was suffragist Florence Brown Cotnam who spoke in favor of a women's suffrage amendment on February 5, 1915. While that amendment was not completely successful, Cotnam was able to persuade the Arkansas governor to hold a special legislative session in 1917. That year Arkansas women won the right to vote in primary elections. In May 1918, between 40,000 and 50,000 white women voted in the primaries. African American voters were restricted from voting in primaries in the state. Further efforts to amend the state constitution took place in 1918, but were also unsuccessful. When the Nineteenth Amendment passed the United States Congress, Arkansas held another special legislative session in July 1919. The amendment was ratified on July 28 and Arkansas became the twelfth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

Ada McPherson Morley was an American author, suffragist and rancher. Early in her time in New Mexico, she and her husband edited a newspaper and took on the Santa Fe Ring both in print and in business matters. Morley became involved with the New Mexico chapter of the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and later served as president. She was also involved in women's suffrage in New Mexico and helped recruit women into the Congressional Union (CU) later in her life. Morley owned a ranch in the Datil Mountains where she raised cattle and was able to host meetings.

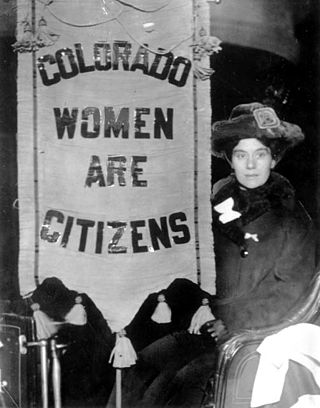

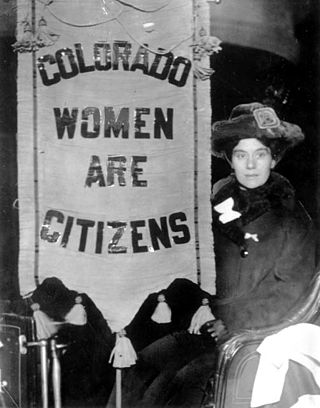

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Colorado. Women's suffrage efforts started in the late 1860s. During the state constitutional convention for Colorado, women received a small win when they were granted the right to vote in school board elections. In 1877, the first women's suffrage referendum was defeated. In 1893, another referendum was successful. After winning the right to vote, Colorado women continued to fight for a federal women's suffrage amendment. While most women were able to vote, it wasn't until 1970 that Native Americans living on reservations were enfranchised.

Women's suffrage began in North Dakota when it was still part of the Dakota Territory. During this time activists worked for women's suffrage, and in 1879, women gained the right to vote at school meetings. This was formalized in 1883 when the legislature passed a law where women would use separate ballots for their votes on school-related issues. When North Dakota was writing its state constitution, efforts were made to include equal suffrage for women, but women were only able to retain their right to vote for school issues. An abortive effort to provide equal suffrage happened in 1893, when the state legislature passed equal suffrage for women. However, the bill was "lost," never signed and eventually expunged from the record. Suffragists continued to hold conventions, raise awareness, and form organizations. The arrival of Sylvia Pankhurst in February 1912 stimulated the creation of more groups, including the statewide Votes for Women League. In 1914, there was a voter referendum on women's suffrage, but it did not pass. In 1917, limited suffrage bills for municipal and presidential suffrage were signed into law. On December 1, 1919, North Dakota became the twentieth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.