Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolinite, Al2Si2O5(OH)4). Most pure clay minerals are white or light-coloured, but natural clays show a variety of colours from impurities, such as a reddish or brownish colour from small amounts of iron oxide.

Fluorite (also called fluorspar) is the mineral form of calcium fluoride, CaF2. It belongs to the halide minerals. It crystallizes in isometric cubic habit, although octahedral and more complex isometric forms are not uncommon.

Fulling, also known as tucking or walking, is a step in woollen clothmaking which involves the cleansing of woven cloth to eliminate (lanolin) oils, dirt, and other impurities, and to make it shrink by friction and pressure. The work delivers a smooth, tightly finished fabric that is insulating and water-repellent. Well-known examples are duffel cloth, first produced in Flanders in the 14th century, and loden, produced in Austria from the 16th century on.

Bentonite is an absorbent swelling clay consisting mostly of montmorillonite which can either be Na-montmorillonite or Ca-montmorillonite. Na-montmorillonite has a considerably greater swelling capacity than Ca-montmorillonite.

Halite, commonly known as rock salt, is a type of salt, the mineral (natural) form of sodium chloride (NaCl). Halite forms isometric crystals. The mineral is typically colorless or white, but may also be light blue, dark blue, purple, pink, red, orange, yellow or gray depending on inclusion of other materials, impurities, and structural or isotopic abnormalities in the crystals. It commonly occurs with other evaporite deposit minerals such as several of the sulfates, halides, and borates. The name halite is derived from the Ancient Greek word for "salt", ἅλς (háls).

A litter box, also known as a sandbox, cat box, litter tray, cat pan, potty, pot or litter pan, is an indoor feces and urine collection box for cats, as well as rabbits, ferrets, miniature pigs, small dogs, and other pets that instinctively or through training will make use of such a repository. They are provided for pets that are permitted free roam of a home but who cannot or do not always go outside to excrete their metabolic waste.

Diatomaceous earth, diatomite, celite or kieselgur/kieselguhr is a naturally occurring, soft, siliceous sedimentary rock that can be crumbled into a fine white to off-white powder. It has a particle size ranging from more than 3 mm to less than 1 μm, but typically 10 to 200 μm. Depending on the granularity, this powder can have an abrasive feel, similar to pumice powder, and has a low density as a result of its high porosity. The typical chemical composition of oven-dried diatomaceous earth is 80–90% silica, with 2–4% alumina, and 0.5–2% iron oxide.

Clay minerals are hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates (e.g. kaolin, Al2Si2O5(OH)4), sometimes with variable amounts of iron, magnesium, alkali metals, alkaline earths, and other cations found on or near some planetary surfaces.

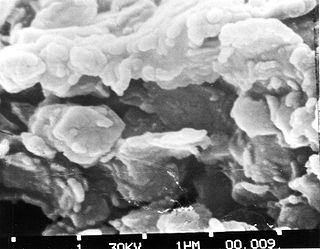

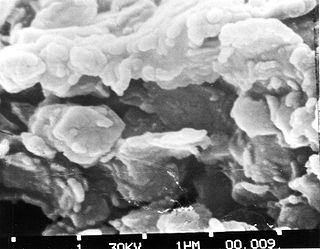

Montmorillonite is a very soft phyllosilicate group of minerals that form when they precipitate from water solution as microscopic crystals, known as clay. It is named after Montmorillon in France. Montmorillonite, a member of the smectite group, is a 2:1 clay, meaning that it has two tetrahedral sheets of silica sandwiching a central octahedral sheet of alumina. The particles are plate-shaped with an average diameter around 1 μm and a thickness of 0.96 nm; magnification of about 25,000 times, using an electron microscope, is required to resolve individual clay particles. Members of this group include saponite, nontronite, beidellite, and hectorite.

Palygorskite or attapulgite is a magnesium aluminium phyllosilicate with the chemical formula (Mg,Al)2Si4O10(OH)·4(H2O) that occurs in a type of clay soil common to the Southeastern United States. It is one of the types of fuller's earth. Some smaller deposits of this mineral can be found in Mexico, where its use is tied to the manufacture of Maya blue in pre-Columbian times.

A smectite is a mineral mixture of various swelling sheet silicates (phyllosilicates), which have a three-layer 2:1 (TOT) structure and belong to the clay minerals. Smectites mainly consist of montmorillonite, but can often contain secondary minerals such as quartz and calcite.

Industrial resources (minerals) are geological materials that are mined for their commercial value, which are not fuel and are not sources of metals but are used in the industries based on their physical and/or chemical properties. They are used in their natural state or after beneficiation either as raw materials or as additives in a wide range of applications.

Carpet cleaning is performed to remove stains, dirt, and allergens from carpets. Common methods include hot water extraction, dry-cleaning, and vacuuming.

A fullo was a Roman fuller or laundry worker, known from many inscriptions from Italy and the western half of the Roman Empire and references in Latin literature, e.g. by Plautus, Martialis and Pliny the Elder. A fullo worked in a fullery or fullonica. There is also evidence that fullones dealt with cloth straight from the loom, though this has been doubted by some modern scholars. In some large farms, fulleries were built where slaves were used to clean the cloth. In several Roman cities, the workshops of fullones, have been found. The most important examples are in Ostia and Pompeii, but fullonicae also have been found in Delos, Florence, Fréjus and near Forlì: in the Archaeological Museum of Forlì, there is an ancient relief with a fullery view. While the small workshops at Delos go back to the 1st century BC, those in Pompeii date from the 1st century AD and the establishments in Ostia and Florence were built during the reign of the Emperors Trajan and Hadrian.

Hectorite is a rare soft, greasy, white clay mineral with a chemical formula of Na0.3(Mg,Li)3Si4O10(OH)2.

The shrink–swell capacity of soils refers to the extent certain clay minerals will expand when wet and retract when dry. Soil with a high shrink–swell capacity is problematic and is known as shrink–swell soil, or expansive soil. The amount of certain clay minerals that are present, such as montmorillonite and smectite, directly affects the shrink-swell capacity of soil. This ability to drastically change volume can cause damage to existing structures, such as cracks in foundations or the walls of swimming pools.

Mining in the United Kingdom produces a wide variety of fossil fuels, metals, and industrial minerals due to its complex geology. In 2013, there were over 2,000 active mines, quarries, and offshore drilling sites on the continental land mass of the United Kingdom producing £34bn of minerals and employing 36,000 people.

The use of medicinal clay in folk medicine goes back to prehistoric times. Indigenous peoples around the world still use clay widely, which is related to geophagy. The first recorded use of medicinal clay goes back to ancient Mesopotamia.

Chaoqi is a traditional Chinese snack. It is made with dough pieces covered with Guanyin clay, a kind of soil. The primary raw materials for making Chaoqi are flour, edible oil, egg, sugar, salt, and sesame. It has various flavors like milk flavor, sesame flavor, and five spices flavor.

Scouring is a preparatory treatment of certain textile materials. Scouring removes soluble and insoluble impurities found in textiles as natural, added and adventitious impurities, for example, oils, waxes, fats, vegetable matter, as well as dirt. Removing these contaminants through scouring prepares the textiles for subsequent processes such as bleaching and dyeing. Though a general term, "scouring" is most often used for wool. In cotton, it is synonymously called "boiling out," and in silk, and "boiling off."