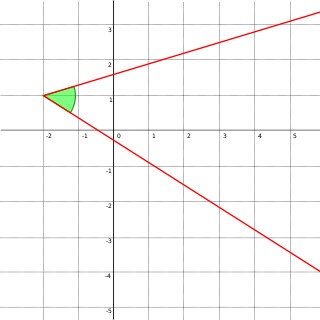

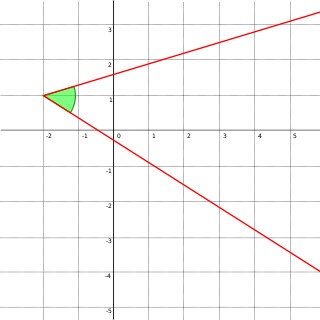

In Euclidean geometry, an angle is the figure formed by two rays, called the sides of the angle, sharing a common endpoint, called the vertex of the angle. Angles formed by two rays are also known as plane angles as they lie in the plane that contains the rays. Angles are also formed by the intersection of two planes; these are called dihedral angles. Two intersecting curves may also define an angle, which is the angle of the rays lying tangent to the respective curves at their point of intersection.

Geodesy is the science of measuring and representing the geometry, gravity, and spatial orientation of the Earth in temporally varying 3D. It is called planetary geodesy when studying other astronomical bodies, such as planets or circumplanetary systems.

The horizon is the apparent curve that separates the surface of a celestial body from its sky when viewed from the perspective of an observer on or near the surface of the relevant body. This curve divides all viewing directions based on whether it intersects the relevant body's surface or not.

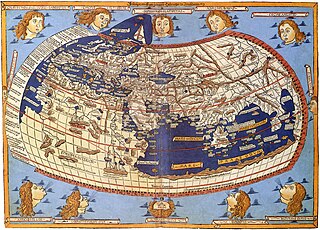

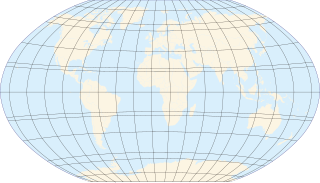

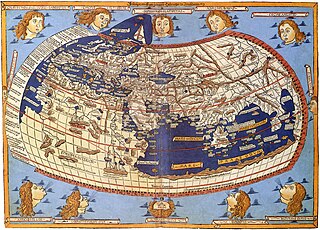

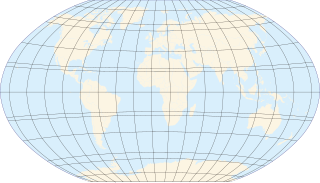

In cartography, a map projection is any of a broad set of transformations employed to represent the curved two-dimensional surface of a globe on a plane. In a map projection, coordinates, often expressed as latitude and longitude, of locations from the surface of the globe are transformed to coordinates on a plane. Projection is a necessary step in creating a two-dimensional map and is one of the essential elements of cartography.

In geometry, two geometric objects are perpendicular if their intersection forms right angles at the point of intersection called a foot. The condition of perpendicularity may be represented graphically using the perpendicular symbol, ⟂. Perpendicular intersections can happen between two lines, between a line and a plane, and between two planes.

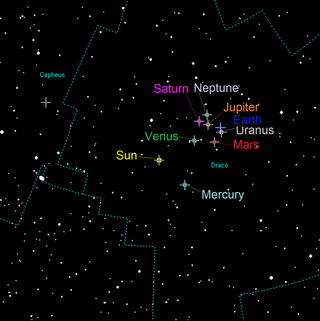

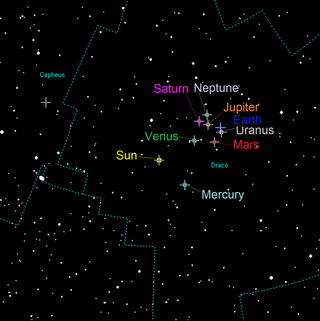

In astronomy, an analemma is a diagram showing the position of the Sun in the sky as seen from a fixed location on Earth at the same mean solar time, as that position varies over the course of a year. The diagram will resemble a figure eight. Globes of Earth often display an analemma as a two-dimensional figure of equation of time vs. declination of the Sun.

A gear is a rotating circular machine part having cut teeth or, in the case of a cogwheel or gearwheel, inserted teeth, which mesh with another (compatible) toothed part to transmit rotational power. While doing so, they can change the torque and rotational speed being transmitted and also change the rotational axis of the power being transmitted. The teeth on the two meshing gears all have the same shape.

A circle of latitude or line of latitude on Earth is an abstract east–west small circle connecting all locations around Earth at a given latitude coordinate line.

In four-dimensional geometry, the 24-cell is the convex regular 4-polytope (four-dimensional analogue of a Platonic solid) with Schläfli symbol {3,4,3}. It is also called C24, or the icositetrachoron, octaplex (short for "octahedral complex"), icosatetrahedroid, octacube, hyper-diamond or polyoctahedron, being constructed of octahedral cells.

Descriptive geometry is the branch of geometry which allows the representation of three-dimensional objects in two dimensions by using a specific set of procedures. The resulting techniques are important for engineering, architecture, design and in art. The theoretical basis for descriptive geometry is provided by planar geometric projections. The earliest known publication on the technique was "Underweysung der Messung mit dem Zirckel und Richtscheyt", published in Linien, Nuremberg: 1525, by Albrecht Dürer. Italian architect Guarino Guarini was also a pioneer of projective and descriptive geometry, as is clear from his Placita Philosophica (1665), Euclides Adauctus (1671) and Architettura Civile, anticipating the work of Gaspard Monge (1746–1818), who is usually credited with the invention of descriptive geometry. Gaspard Monge is usually considered the "father of descriptive geometry" due to his developments in geometric problem solving. His first discoveries were in 1765 while he was working as a draftsman for military fortifications, although his findings were published later on.

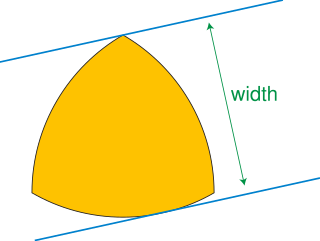

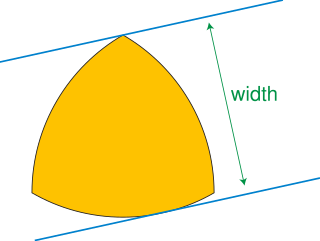

In geometry, a curve of constant width is a simple closed curve in the plane whose width is the same in all directions. The shape bounded by a curve of constant width is a body of constant width or an orbiform, the name given to these shapes by Leonhard Euler. Standard examples are the circle and the Reuleaux triangle. These curves can also be constructed using circular arcs centered at crossings of an arrangement of lines, as the involutes of certain curves, or by intersecting circles centered on a partial curve.

In geometry, the 16-cell is the regular convex 4-polytope (four-dimensional analogue of a Platonic solid) with Schläfli symbol {3,3,4}. It is one of the six regular convex 4-polytopes first described by the Swiss mathematician Ludwig Schläfli in the mid-19th century. It is also called C16, hexadecachoron, or hexdecahedroid [sic?].

In geometry and science, a cross section is the non-empty intersection of a solid body in three-dimensional space with a plane, or the analog in higher-dimensional spaces. Cutting an object into slices creates many parallel cross-sections. The boundary of a cross-section in three-dimensional space that is parallel to two of the axes, that is, parallel to the plane determined by these axes, is sometimes referred to as a contour line; for example, if a plane cuts through mountains of a raised-relief map parallel to the ground, the result is a contour line in two-dimensional space showing points on the surface of the mountains of equal elevation.

In classical geometry, a radius of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The name comes from the Latin radius, meaning ray but also the spoke of a chariot wheel. The typical abbreviation and mathematical variable name for radius is R or r. By extension, the diameter D is defined as twice the radius:

In optics, a ray is an idealized geometrical model of light or other electromagnetic radiation, obtained by choosing a curve that is perpendicular to the wavefronts of the actual light, and that points in the direction of energy flow. Rays are used to model the propagation of light through an optical system, by dividing the real light field up into discrete rays that can be computationally propagated through the system by the techniques of ray tracing. This allows even very complex optical systems to be analyzed mathematically or simulated by computer. Ray tracing uses approximate solutions to Maxwell's equations that are valid as long as the light waves propagate through and around objects whose dimensions are much greater than the light's wavelength. Ray optics or geometrical optics does not describe phenomena such as diffraction, which require wave optics theory. Some wave phenomena such as interference can be modeled in limited circumstances by adding phase to the ray model.

An orbital pole is either point at the ends of the orbital normal, an imaginary line segment that runs through a focus of an orbit and is perpendicular to the orbital plane. Projected onto the celestial sphere, orbital poles are similar in concept to celestial poles, but are based on the body's orbit instead of its equator.

In Gaussian optics, the cardinal points consist of three pairs of points located on the optical axis of a rotationally symmetric, focal, optical system. These are the focal points, the principal points, and the nodal points; there are two of each. For ideal systems, the basic imaging properties such as image size, location, and orientation are completely determined by the locations of the cardinal points; in fact, only four points are necessary: the two focal points and either the principal points or the nodal points. The only ideal system that has been achieved in practice is a plane mirror, however the cardinal points are widely used to approximate the behavior of real optical systems. Cardinal points provide a way to analytically simplify an optical system with many components, allowing the imaging characteristics of the system to be approximately determined with simple calculations.

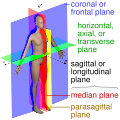

An anatomical plane is a hypothetical plane used to transect the body, in order to describe the location of structures or the direction of movements. In human and non-human anatomy, three principal planes are used:

In astronomy, geography, and related sciences and contexts, a direction or plane passing by a given point is said to be vertical if it contains the local gravity direction at that point.