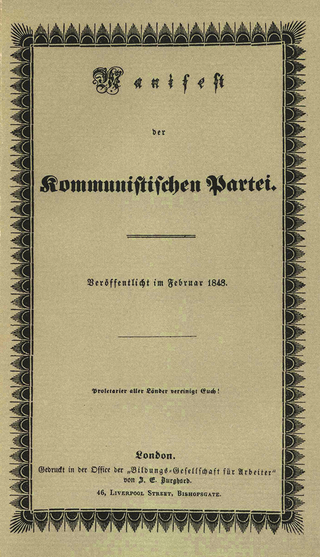

The Communist Manifesto, originally the Manifesto of the Communist Party, is a political pamphlet written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, commissioned by the Communist League and originally published in London in 1848. The text is the first and most systematic attempt by Marx and Engels to codify for wide consumption the historical materialist idea that "the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles", in which social classes are defined by the relationship of people to the means of production. Published amid the Revolutions of 1848 in Europe, the Manifesto remains one of the world's most influential political documents.

The bourgeoisie are a class of business owners and merchants which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted with the proletariat by their wealth, political power, and education, as well as their access to and control of cultural, social and financial capital.

Karl Marx's theory of alienation describes the estrangement of people from aspects of their human nature as a consequence of the division of labor and living in a society of stratified social classes. The alienation from the self is a consequence of being a mechanistic part of a social class, the condition of which estranges a person from their humanity.

In Marxist philosophy, cultural hegemony is the dominance of a culturally diverse society by the ruling class who shape the culture of that society—the beliefs and explanations, perceptions, values, and mores—so that the worldview of the ruling class becomes the accepted cultural norm. As the universal dominant ideology, the ruling-class worldview misrepresents the social, political, and economic status quo as natural, inevitable, and perpetual social conditions that benefit every social class, rather than as artificial social constructs that benefit only the ruling class.

Petite bourgeoisie is a term that refers to a social class composed of semi-autonomous peasants and small-scale merchants. They are named as such because their politico-economic ideological stance in times of stability is reflective of the proper haute bourgeoisie. In regular times, the petite bourgeoisie seek to identify themselves with the haute bourgeoisie, whose bourgeois morality, conduct and lifestyle they aspire and strive to imitate.

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as "historical materialism," to understand class relations and social conflict. It also uses a dialectical perspective to view social transformation. Marxism originates from the works of 19th-century German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marxism has developed over time into various branches and schools of thought, As a result, there is no single, definitive Marxist theory. Marxism has had a profound impact in shaping the modern world, with various left-wing and far-left political movements taking inspiration from it in varying local contexts.

Economic determinism is a socioeconomic theory that economic relationships are the foundation upon which all other societal and political arrangements in society are based. The theory stresses that societies are divided into competing economic classes whose relative political power is determined by the nature of the economic system.

New Democracy, or the New Democratic Revolution, is a type of democracy in Marxism, based on Mao Zedong's Bloc of Four Social Classes theory in post-revolutionary China which argued originally that democracy in China would take a path that was decisively distinct from that in any other country. He also said every colonial or semi-colonial country would have its own unique path to democracy, given that particular country's own social and material conditions. Mao labeled representative democracy in the Western nations as Old Democracy, characterizing parliamentarianism as just an instrument to promote the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie/land-owning class through manufacturing consent. He also found his concept of New Democracy not in contrast with the Soviet-style dictatorship of the proletariat which he assumed would be the dominant political structure of a post-capitalist world. Mao spoke about how he wanted to create a New China, a country freed from the feudal and semi-feudal aspects of its old culture as well as Japanese imperialism.

Marxian class theory asserts that an individual's position within a class hierarchy is determined by their role in the production process, and argues that political and ideological consciousness is determined by class position. A class is those who share common economic interests, are conscious of those interests, and engage in collective action which advances those interests. Within Marxian class theory, the structure of the production process forms the basis of class construction.

In the Marxist theory of historical materialism, a mode of production is a specific combination of the:

Classical Marxism is the body of economic, philosophical, and sociological theories expounded by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in their works, as contrasted with orthodox Marxism, Marxism–Leninism, and autonomist Marxism which emerged after their deaths. The core concepts of classical Marxism include alienation, base and superstructure, class consciousness, class struggle, exploitation, historical materialism, ideology, revolution; and the forces, means, modes, and relations of production. Marx's political praxis, including his attempt to organize a professional revolutionary body in the First International, often served as an area of debate for subsequent theorists.

Marxist literary criticism is a theory of literary criticism based on the historical materialism developed by philosopher and economist Karl Marx. Marxist critics argue that even art and literature themselves form social institutions and have specific ideological functions, based on the background and ideology of their authors. The English literary critic and cultural theorist Terry Eagleton defines Marxist criticism this way: "Marxist criticism is not merely a 'sociology of literature', concerned with how novels get published and whether they mention the working class. Its aims to explain the literary work more fully; and this means a sensitive attention to its forms, styles and, meanings. But it also means grasping those forms styles and meanings as the product of a particular history." In Marxist criticism, class struggle and relations of production are the central instruments in analysis.

In Marxist philosophy, the dictatorship of the proletariat is a condition in which the proletariat, or working class, holds control over state power. The dictatorship of the proletariat is the transitional phase from a capitalist and a communist economy, whereby the post-revolutionary state seizes the means of production, mandates the implementation of direct elections on behalf of and within the confines of the ruling proletarian state party, and institutes elected delegates into representative workers' councils that nationalise ownership of the means of production from private to collective ownership. During this phase, the administrative organizational structure of the party is to be largely determined by the need for it to govern firmly and wield state power to prevent counterrevolution, and to facilitate the transition to a lasting communist society.

Marxist philosophy or Marxist theory are works in philosophy that are strongly influenced by Karl Marx's materialist approach to theory, or works written by Marxists. Marxist philosophy may be broadly divided into Western Marxism, which drew from various sources, and the official philosophy in the Soviet Union, which enforced a rigid reading of what Marx called dialectical materialism, in particular during the 1930s. Marxist philosophy is not a strictly defined sub-field of philosophy, because the diverse influence of Marxist theory has extended into fields as varied as aesthetics, ethics, ontology, epistemology, social philosophy, political philosophy, the philosophy of science, and the philosophy of history. The key characteristics of Marxism in philosophy are its materialism and its commitment to political practice as the end goal of all thought. The theory is also about the struggles of the proletariat and their reprimand of the bourgeoisie.

The proletariat is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power. A member of such a class is a proletarian or a proletaire. Marxist philosophy regards the proletariat under conditions of capitalism as an exploited class— forced to accept meager wages in return for operating the means of production, which belong to the class of business owners, the bourgeoisie.

Permanent revolution is the strategy of a revolutionary class pursuing its own interests independently and without compromise or alliance with opposing sections of society. As a term within Marxist theory, it was first coined by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels as early as 1850, but since then it has been used to refer to different concepts by different theorists, most notably Leon Trotsky.

Historical materialism is Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx located historical change in the rise of class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods.

A proletarian revolution or proletariat revolution is a social revolution in which the working class attempts to overthrow the bourgeoisie and change the previous political system. Proletarian revolutions are generally advocated by socialists, communists and anarchists.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Marxism:

Bourgeois revolution is a term used in Marxist theory to refer to a social revolution that aims to destroy a feudal system or its vestiges, establish the rule of the bourgeoisie, and create a bourgeois (capitalist) state. In colonised or subjugated countries, bourgeois revolutions often take the form of a war of national independence. The Dutch, English, American, and French revolutions are considered the archetypal bourgeois revolutions, in that they attempted to clear away the remnants of the medieval feudal system, so as to pave the way for the rise of capitalism. The term is usually used in contrast to "proletarian revolution", and is also sometimes called a "bourgeois-democratic revolution".