The economy of Canada is a highly developed mixed economy. It is the 9th largest GDP by nominal and 15th largest GDP by PPP in the world. As with other developed nations, the country's economy is dominated by the service industry which employs about three quarters of Canadians. Canada has the third highest total estimated value of natural resources, valued at US$33.2 trillion in 2019. It has the world's third largest proven oil reserves and is the fourth largest exporter of crude oil. It is also the fourth largest exporter of natural gas. Canada is considered an "energy superpower" due to its abundant natural resources and a fairly small population of 38 million inhabitants, in relation to its land area.

The Economy of Chile is a market economy and high-income economy as ranked by the World Bank. The country is considered one of South America's most prosperous nations, leading the region in competitiveness, income per capita, globalization, economic freedom, and low perception of corruption. Although Chile has high economic inequality, as measured by the Gini index, it is close to the regional mean.

The economy of Colombia is the fourth largest in Latin America as measured by gross domestic product. Colombia has experienced a historic economic boom over the last decade. Throughout the 20th century, Colombia was Latin America's 4th and 3rd largest economy when measured by Real GDP at chained PPPs. Between 2012 and 2014, it became the 3rd largest economy in Latin America by nominal GDP. As of 2018, the GDP (PPP) per capita has increased to over US$14,000, and Real GDP at chained PPPs increased from US$250 billion in 1990 to nearly US$800 billion. Poverty levels were as high as 65% in 1990, but decreased to under 30% by 2014, and 27% by 2018. They had decreased by an average of 1.35% per year since 1990.

The economy of Honduras is based mostly on agriculture, which accounts for 14% of its gross domestic product (GDP) in 2013. The country's leading export is coffee (US$340 million), which accounted for 22% of the total Honduran export revenues. Bananas, formerly the country's second-largest export until being virtually wiped out by 1998's Hurricane Mitch, recovered in 2000 to 57% of pre-Mitch levels. Cultivated shrimp is another important export sector. Since the late 1970s, towns in the north began industrial production through maquiladoras, especially in San Pedro Sula and Puerto Cortés.

The economy of Jamaica is heavily reliant on services, accounting for 70% of the country's GDP. Jamaica has natural resources, primarily bauxite, and an ideal climate conducive to agriculture and tourism. The discovery of bauxite in the 1940s and the subsequent establishment of the bauxite-alumina industry shifted Jamaica's economy from sugar and bananas. By the 1970s, Jamaica had emerged as a world leader in export of these minerals as foreign investment increased.

The economy of Mexico is a developing market economy. It is the 15th largest in the world in nominal GDP terms and the 11th largest by purchasing power parity, according to the International Monetary Fund. Since the 1994 crisis, administrations have improved the country's macroeconomic fundamentals. Mexico was not significantly influenced by the 2002 South American crisis, and maintained positive, although low, rates of growth after a brief period of stagnation in 2001. However, Mexico was one of the Latin American nations most affected by the 2008 recession with its gross domestic product contracting by more than 6% in that year.

The North American Free Trade Agreement was an agreement signed by Canada, Mexico, and the United States that created a trilateral trade bloc in North America. The agreement came into force on January 1, 1994, and superseded the 1988 Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement between the United States and Canada. The NAFTA trade bloc formed one of the largest trade blocs in the world by gross domestic product.

A tariff is a tax imposed by a government of a country or of a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and policy that taxes foreign products to encourage or safeguard domestic industry. Tariffs are among the most widely used instruments of protectionism, along with import and export quotas.

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. Proponents argue that protectionist policies shield the producers, businesses, and workers of the import-competing sector in the country from foreign competitors; however, they also reduce trade and adversely affect consumers in general, and harm the producers and workers in export sectors, both in the country implementing protectionist policies and in the countries protected against.

A maquiladora, or maquila, is a company that allows factories to be largely duty free and tariff-free. These factories take raw materials and assemble, manufacture, or process them and export the finished product. These factories and systems are present throughout Latin America, including Mexico, Paraguay, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. Maquiladoras date back to 1964, when the Mexican government introduced the Programa de Industrialización Fronteriza. Specific programs and laws have made Mexico's maquila industry grow rapidly.

The economy of North America comprises more than 579 million people in its 23 sovereign states and 15 dependent territories. It is marked by a sharp division between the predominantly English speaking countries of Canada and the United States, which are among the wealthiest and most developed nations in the world, and countries of Central America and the Caribbean in the former Latin America that are less developed. Mexico and Caribbean nations of the Commonwealth of Nations are between the economic extremes of the development of North America.

The economic policies of Bill Clinton administration, referred to by some as Clintonomics, encapsulates the economic policies of United States President Bill Clinton that were implemented during his presidency, which lasted from January 1993 to January 2001.

Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) is a federal program of the United States government to act as a way to reduce the damaging impact of imports felt by certain sectors of the U.S. economy. The current structure features four components of Trade Adjustment Assistance: for workers, firms, farmers, and communities. Each cabinet-level department was tasked with a different sector of the overall Trade Adjustment Assistance program. The program for workers is the largest, and administered by the U.S. Department of Labor. The program for farmers is administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the firms and communities programs are administered by the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Tariffs have historically served a key role in the trade policy of the United States. Their purpose was to generate revenue for the federal government and to allow for import substitution industrialization by acting as a protective barrier around infant industries. They also aimed to reduce the trade deficit and the pressure of foreign competition. Tariffs were one of the pillars of the American System that allowed the rapid development and industrialization of the United States. The United States pursued a protectionist policy from the beginning of the 19th century until the middle of the 20th century. Between 1861 and 1933, they had one of the highest average tariff rates on manufactured imports in the world. However American agricultural and industrial were cheaper than rival products and the tariff had an impact primarily on wool products. After 1942 the U.S. promoted worldwide free trade.

Manufacturing in the United States is a vital sector. The United States is the world's third largest manufacturer with a record high real output in Q1 2018 of $2.00 trillion well above the 2007 peak before the Great Recession of $1.95 trillion. The U.S. manufacturing industry employed 12.35 million people in December 2016 and 12.56 million in December 2017, an increase of 207,000 or 1.7%. Though still a large part of the US economy, in Q1 2018 manufacturing contributed less to GDP than the 'Finance, insurance, real estate, rental, and leasing' sector, the 'Government' sector, or 'Professional and business services' sector.

The share of the industry of Colombia in the country's gross domestic product (GDP) has shifted significantly in the last few decades. Data from the World Bank show that between 1965 and 1989 the share of industry—including construction, manufacturing, and mining—increased from 27 percent to 38 percent of GDP. However, since then the share has fallen considerably, down to approximately 29 percent of GDP in 2007. This pattern is about the average for middle-income countries.

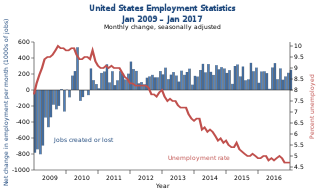

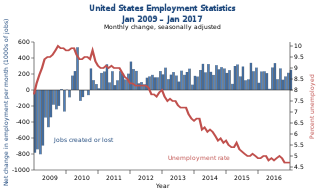

Job creation and unemployment are affected by factors such as aggregate demand, global competition, education, automation, and demographics. These factors can affect the number of workers, the duration of unemployment, and wage rates.

The economic policy of the Donald Trump administration was characterized by the individual and corporate tax cuts, attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act ("Obamacare"), trade protectionism, immigration restriction, deregulation focused on the energy and financial sectors, and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The North American Free Trade Agreement of 1994's effects on Mexico have long been overshadowed by the debate on the Agreement's effects on the economy of the United States. As a kind partner in the agreement, the effects that NAFTA has had on the Mexican economy is essential to understanding NAFTA on a whole. A key factor in this discussion is the way the Agreement was presented to Mexico; namely, that it would increase development of the Mexican economy by providing more middle class jobs that would enable more Mexicans to lift themselves out of the lower classes. Thus, wages, employment, attitudes, and migration all present essential areas of analyses to understand effects NAFTA has had on the Mexican economy.

The Trump tariffs are a series of United States tariffs imposed during the presidency of Donald Trump as part of his "America First" economic policy to reduce the United States trade deficit by shifting American trade policy from multilateral free trade agreements to bilateral trade deals. In January 2018, Trump imposed tariffs on solar panels and washing machines of 30 to 50 percent. In March 2018, he imposed tariffs on steel (25%) and aluminum (10%) from most countries, which, according to Morgan Stanley, covered an estimated 4.1 percent of U.S. imports. In June 2018, this was extended to the European Union, Canada, and Mexico. The Trump administration separately set and escalated tariffs on goods imported from China, leading to a trade war.