Related Research Articles

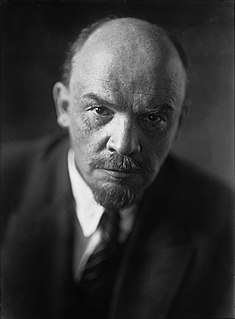

The Bolsheviks, also known in English as the Bolshevists, were a radical, far-left, and revolutionary Marxist faction founded by Vladimir Lenin and Alexander Bogdanov that split from the Menshevik faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), a revolutionary socialist political party formed in 1898, at its Second Party Congress in 1903.

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) was the founding and ruling political party of Soviet Russia and the Soviet Union. The CPSU was the sole governing party of the Soviet Union until 1990 when the Congress of People's Deputies modified Article 6 of the 1977 Soviet Constitution, which had previously granted the CPSU a monopoly over the political system.

Lev Davidovich Bronstein, better known as Leon Trotsky, was a Ukrainian revolutionary, political theorist and politician. Ideologically a communist, he developed a variant of Marxism known as Trotskyism.

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat, led by a revolutionary vanguard party, as the political prelude to the establishment of communism. The function of the Leninist vanguard party is to provide the working classes with the political consciousness and revolutionary leadership necessary to depose capitalism in the Russian Empire (1721–1917). Leninist revolutionary leadership is based upon The Communist Manifesto (1848) identifying the communist party as "the most advanced and resolute section of the working class parties of every country; that section which pushes forward all others." As the vanguard party, the Bolsheviks viewed history through the theoretical framework of dialectical materialism, which sanctioned political commitment to the successful overthrow of capitalism, and then to instituting socialism; and, as the revolutionary national government, to realize the socio-economic transition by all means.

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist and Bolshevik–Leninist. He supported founding a vanguard party of the proletariat, proletarian internationalism and a dictatorship of the proletariat based on working class self-emancipation and mass democracy. Trotskyists are critical of Stalinism as they oppose Joseph Stalin's theory of socialism in one country in favor of Trotsky's theory of permanent revolution. Trotskyists also criticize the bureaucracy that developed in the Soviet Union under Stalin.

The ten years 1917–1927 saw a radical transformation of the Russian Empire into a communist state, the Soviet Union. Soviet Russia covers 1917–1922 and Soviet Union covers the years 1922 to 1991. After the Russian Civil War (1917–

The 'April Theses' were a series of ten directives issued by the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin upon his return to Petrograd from his exile in Switzerland via Germany and Finland. Theses were mostly aimed at fellow Bolsheviks in Russia and returning to Russia from exile. He called for soviets, denounced liberals and social revolutionaries in the Provisional Government, called for Bolsheviks not to cooperate with the government, and called for new communist policies. The April Theses influenced the July Days and October Revolution in the next months and are identified with Leninism.

Mikhail Ivanovich Kalinin, known familiarly by Soviet citizens as "Kalinych", was an Old Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet politician. He served as head of state of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and later of the Soviet Union from 1919 to 1946. From 1926, he was a member of the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

The history of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was generally perceived as covering that of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party from which it evolved. The date 1912 is often identified as the time of the formation of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union as a distinct party, and its history since then can roughly be divided into the following periods:

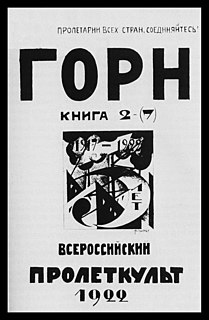

Proletkult, a portmanteau of the Russian words "proletarskaya kultura", was an experimental Soviet artistic institution that arose in conjunction with the Russian Revolution of 1917. This organization, a federation of local cultural societies and avant-garde artists, was most prominent in the visual, literary, and dramatic fields. Proletkult aspired to radically modify existing artistic forms by creating a new, revolutionary working-class aesthetic, which drew its inspiration from the construction of modern industrial society in backward, agrarian Russia.

Printed media in the Soviet Union, i.e., newspapers, magazines and journals, were under strict control of the Communist Party and the Soviet state. The desire to disseminate propaganda is believed to have been the driving force behind the creation of the early Soviet newspapers. Until recently, newspapers were the essential means of communicating with the public, which meant that they were the most powerful way available to spread propaganda and capture the hearts of the populace. Additionally, within the Soviet Union the press evolved into the messenger for the orders from the Central Committee to the party officials and activists. Due to this important role, the Soviet papers were both prestigious in the society and an effective means to control the masses. However, manipulation initially was not the only purpose of the Soviet Press.

Matvei Konstantinovich Muranov was a Ukrainian-born Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician and statesman.

Mykola Oleksiyovych Skrypnyk was a Ukrainian Bolshevik revolutionary and Communist leader who was a proponent of the Ukrainian Republic's independence, and led the cultural Ukrainization effort in Soviet Ukraine. When the policy was reversed and he was removed from his position, he committed suicide rather than be forced to recant his policies in a show trial. He also was the Head of the Ukrainian People's Commissariat, the post of the today's Prime-Minister.

Yemelyan Mikhailovich Yaroslavsky was a Bolshevik revolutionary, Communist Party functionary, journalist and historian.

Rabotnitsa is a women's journal, published in the Soviet Union and Russia and one of the oldest Russian magazines for women and families. Founded in 1914, and first published on Women's Day, it is the first socialist women's journal, and the most politically left of the women's periodicals. While the journal's beginnings are attributed to Lenin and several women who were close to him, he did not contribute to the first seven issues.

Pravda is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, formerly the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the country with a circulation of 11 million. The newspaper began publication on 5 May 1912 in the Russian Empire, but was already extant abroad in January 1911. It emerged as a leading newspaper of the Soviet Union after the October Revolution. The newspaper was an organ of the Central Committee of the CPSU between 1912 and 1991.

The New Economic Policy (NEP) was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, both subject to state control," while socialized state enterprises would operate on "a profit basis."

In Marxist philosophy, the dictatorship of the proletariat is a state of affairs in which the proletariat holds political power. The dictatorship of the proletariat is the intermediate stage between a capitalist economy and a communist economy, whereby the post-revolutionary state seizes the means of production, compels the implementation of direct elections on behalf of and within the confines of the ruling proletarian state party, and instituting elected delegates into representative workers' councils that nationalise ownership of the means of production from private to collective ownership. During this phase, the administrative organizational structure of the party is to be largely determined by the need for it to govern firmly and wield state power to prevent counterrevolution and to facilitate the transition to a lasting communist society.

Anti-Leninism is opposition to the political philosophy Leninism as advocated by Vladimir Lenin.

Foundations of Leninism is a 1924 collection by Joseph Stalin of nine lectures he delivered at Sverdlov University that year. It was published by the Soviet newspaper, Pravda.

References

- ↑ See Peter Kenez, The birth of the propaganda state. Soviet methods of mass mobilization, 1917-1929

- ↑ O partiinoi I sovetskoy pechati: sbornik dokumentov, Moscow: Izdatel'stvo "Pravda", 1954, p. 212.

- ↑ See the Bolshaya Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya ( The Great Soviet Encyclopedia ), ed. 1974,: Worker and village correspondents' movement.

- ↑ Matthew Lenoe, p 144 referring to statistics in the Rabotnitsa archive in Rossiiskii Tsentr Khraneniia i Izucheniia Dokumentov Noveishei Istorii (RTsKhIDNI), 610, pp. 1, d. 8, ll. 1–10, 15, 19–20.

- ↑ Mathew E. Lenoe, pp. 144–146.

- ↑ Jeffrey Brooks, pp. 18–35.

- ↑ On the shift toward direct Party supervision of the worker correspondents' movement in 1926, see, e.g., Julie Kay Mueller, A New Kind of Newspaper: The Origins and Development of a Soviet Institution, 1921–1928 pp. 264–315, Ph.D. diss., University of California/Berkeley, 1992.

- ↑ On the worker and village correspondents movement as a tool for educating workers and peasants in Bolshevik language, see Jeffrey Brooks, "Public and Private Values in the Soviet Press, 1921–1928", pp. 18–35; Michael Gorham, Tongue-Tied Writers: The Rabsel'kor Movement and the voice of the "new intelligentsiia" in early Soviet Russia, pp. 412–429; Matthew Lenoe, Stalinist Mass Journalism, pp. 34–44.

- ↑ Carl Schreck, Proletarian Bloggers Celebrate a Milestone.