Trogir is a historic town and harbour on the Adriatic coast in Split-Dalmatia County, Croatia, with a population of 10,923 (2011) and a total municipal population of 13,192 (2011). The historic city of Trogir is situated on a small island between the Croatian mainland and the island of Čiovo. It lies 27 kilometres west of the city of Split.

Solin is a town and a suburb of Split, in Split-Dalmatia county, Croatia. It is situated right northeast of Split, on the Adriatic Sea and the river Jadro.

Tourism in Croatia is a major industry of country's economy, accounting for almost 20% of Croatia's gross domestic product (GDP) as of 2021.

Diocletian's Palace was built at the end of the third century AD as a residence for the Roman emperor Diocletian, and today forms about half of the old town of Split, Croatia. While it is referred to as a "palace" because of its intended use as the retirement residence of Diocletian, the term can be misleading as the structure is massive and more resembles a large fortress: about half of it was for Diocletian's personal use, and the rest housed the military garrison.

Mislav was a duke in Croatia from around 835 until his death around 845.

Frane Bulić was a Croatian priest, archaeologist, and historian.

The Church of the Holy Salvation or Holy Saviour was a Pre-Romanesque church in the Dalmatian Hinterland, Croatia, whose ruins are now a historic site. It is located in the small village of Cetina, near the spring of the river Cetina, 8 km northwest from the town of Vrlika.

The Klis Fortress is a medieval fortress situated above the village of Klis, near Split, Croatia. From its origin as a small stronghold built by the ancient Illyrian tribe Dalmatae, to a role as royal castle and seat of many Croatian kings, to its final development as a large fortress during the Ottoman wars in Europe, Klis Fortress has guarded the frontier, being lost and re-conquered several times throughout its two-thousand-year-long history. Due to its location on a pass that separates the mountains Mosor and Kozjak, the fortress served as a major source of defense in Dalmatia, especially against the Ottoman Empire. It has been a crossroad between the Mediterranean Sea and the Balkans.

The Cathedral of Saint Domnius, known locally as the Sveti Dujam or colloquially Sveti Duje, is the Catholic cathedral in Split, Croatia. The cathedral is the seat of the Archdiocese of Split-Makarska, currently headed by Archbishop Zdenko Križić. The Cathedral of St. Domnius is a complex of a church, formed from an Imperial Roman mausoleum, with a bell tower; strictly the church is dedicated to the Virgin Mary, and the bell tower to Saint Domnius. Together they form the Cathedral of St. Domnius.

The Aqueduct of Diocletian is an ancient Roman aqueduct near Split, Croatia constructed during the Roman Empire to supply water to the palace of the emperor Diocletian, who was Augustus 284 to 305 AD, retired to Spalatum, and died there in 311.

Croatian Pre-Romanesque art and architecture or Old Croatian Art is Pre-Romanesque art and architecture of Croats from their arrival at Balkans till the end of the 11th century when begins the dominance of Romanesque style in art; that was the time of Croatian rulers.

Trpimir I was a duke in Croatia from around 845 until his death in 864. He is considered the founder of the Trpimirović dynasty that ruled in Croatia, with interruptions, from around 845 until 1091. Although he was formally vassal of the Frankish Emperor Lothair I, Trpimir used Frankish-Byzantine conflicts to rule on his own.

The Duchy of Croatia was a medieval state that was established by White Croats who migrated into the area of the former Roman province of Dalmatia c. 7th century CE. Throughout its existence the Duchy had several seats – namely, Klis, Solin, Knin, Bijaći and Nin. It comprised the littoral – the coastal part of today's Croatia – except Istria, and included a large part of the mountainous hinterland as well. The Duchy was in the center of competition between the Carolingian Empire and the Byzantine Empire for rule over the area. Croatian rivalry with Venice emerged in the first decades of the 9th century and would continue through the following centuries. Croatia also waged battles with the Bulgarian Empire and with the Arabs; it also sought to extend its control over important coastal cities under the rule of Byzantium. Croatia experienced periods of vassalage to the Franks or to the Byzantines and of de facto independence until 879, when Duke Branimir was recognized as an independent ruler by Pope John VIII. The Duchy was ruled by the Trpimirović and Domagojević dynasties from 845 to 1091. Around 925, during the rule of Tomislav, Croatia became a kingdom.

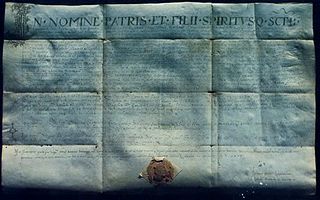

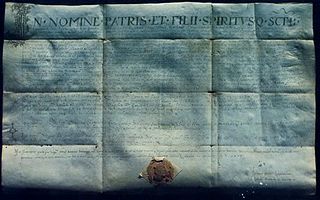

Charter of Duke Trpimir, also known as Trpimir's deed of donation is the oldest preserved document of the Croatian law, the oldest from the court of one of the Croatian rulers and the first national document which mentions the Croatian name. Charter, dated to 4 March 852, is not preserved in its original form but in five subsequent transcripts out of which the oldest is from year 1568.

The Golden Gate, or "the Northern Gate", is one of the four principal Roman gates into the stari grad of Split. Built as the main gate of Diocletian's Palace, it was elaborately decorated to mark its status. Over the course of the Middle Ages, the gate was sealed off and lost its columns and statuary. It was reopened and repaired in modern times and now serves as a tourist attraction.

The Iron Gate, or "the Western Gate", is one of the four principal Roman gates into the stari grad of Split that was once Diocletian's Palace. Originally a military gate from which troops entered the complex, the gate is the only one to have remained in continuous use to the present day.

The Silver Gate, or "the Eastern Gate", is one of the four principal Roman gates into the stari grad of Split that was once Diocletian's Palace. The gate faces east towards the Roman town of Epetia, today Stobreč.

The Cellars of Diocletian's Palace, sometimes referred to as the "basement halls", is a set of substructures, located at the southern end of Diocletian's Palace, that once held up the private apartments of Emperor Diocletian and represent one of the best preserved ancient complexes of their kind in the world.

The Belltower of the Church of Our Lady of the Belfry is a disused Roman Catholic church in Split, Croatia. Built into a small space within the ancient Iron Gate of Diocletian's western wall. Today little survives of the building, apart from the belltower, one of the oldest in Croatia.

Rupotine is an archeological site near Solin, Croatia, which is believed by Croatian archaeologists to be the site of medieval Rižinice monastery. It is considered one of most significant early medieval Croatian archeological sites due to the inscription of duke Trpimir "PRO DUCE TREPIME(ro)" which was found here.