Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other vertebrates. Human malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, fatigue, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. Symptoms usually begin 10 to 15 days after being bitten by an infected Anopheles mosquito. If not properly treated, people may have recurrences of the disease months later. In those who have recently survived an infection, reinfection usually causes milder symptoms. This partial resistance disappears over months to years if the person has no continuing exposure to malaria.

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to Plasmodium falciparum that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg cramps, quinine is not recommended for this purpose due to the risk of serious side effects. It can be taken by mouth or intravenously. Malaria resistance to quinine occurs in certain areas of the world. Quinine is also used as an ingredient in tonic water and other beverages to impart a bitter taste.

Laudanum is a tincture of opium containing approximately 10% powdered opium by weight. Laudanum is prepared by dissolving extracts from the opium poppy in alcohol (ethanol).

Cinchona is a genus of flowering plants in the family Rubiaceae containing at least 23 species of trees and shrubs. All are native to the tropical Andean forests of western South America. A few species are reportedly naturalized in Central America, Jamaica, French Polynesia, Sulawesi, Saint Helena in the South Atlantic, and São Tomé and Príncipe off the coast of tropical Africa, and others have been cultivated in India and Java, where they have formed hybrids.

Tonic water is a carbonated soft drink in which quinine is dissolved. Originally used as a prophylactic against malaria, nowadays tonic water usually has a significantly lower quinine content and is often sweetened. It is consumed for its distinctive bitter flavor and is frequently used in mixed drinks, particularly in gin and tonic.

Paregoric, or camphorated tincture of opium, also known as tinctura opii camphorata, is a traditional patent medicine known for its antidiarrheal, antitussive, and analgesic properties.

Antimalarial medications or simply antimalarials are a type of antiparasitic chemical agent, often naturally derived, that can be used to treat or to prevent malaria, in the latter case, most often aiming at two susceptible target groups, young children and pregnant women. As of 2018, modern treatments, including for severe malaria, continued to depend on therapies deriving historically from quinine and artesunate, both parenteral (injectable) drugs, expanding from there into the many classes of available modern drugs. Incidence and distribution of the disease is expected to remain high, globally, for many years to come; moreover, known antimalarial drugs have repeatedly been observed to elicit resistance in the malaria parasite—including for combination therapies featuring artemisinin, a drug of last resort, where resistance has now been observed in Southeast Asia. As such, the needs for new antimalarial agents and new strategies of treatment remain important priorities in tropical medicine. As well, despite very positive outcomes from many modern treatments, serious side effects can impact some individuals taking standard doses.

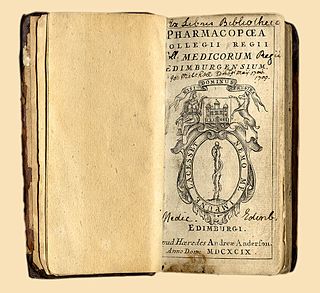

A pharmacopoeia, pharmacopeia, or pharmacopoea, in its modern technical sense, is a book containing directions for the identification of compound medicines, and published by the authority of a government or a medical or pharmaceutical society.

Plasmodium falciparum is a unicellular protozoan parasite of humans, and the deadliest species of Plasmodium that causes malaria in humans. The parasite is transmitted through the bite of a female Anopheles mosquito and causes the disease's most dangerous form, falciparum malaria. It is responsible for around 50% of all malaria cases. P. falciparum is therefore regarded as the deadliest parasite in humans. It is also associated with the development of blood cancer and is classified as a Group 2A (probable) carcinogen.

Blackwater fever is a complication of malaria infection in which red blood cells burst in the bloodstream (hemolysis), releasing hemoglobin directly into the blood vessels and into the urine, frequently leading to kidney failure. The disease was first linked to malaria by the Sierra Leone Creole physician John Farrell Easmon in his 1884 pamphlet entitled The Nature and Treatment of Blackwater Fever. Easmon coined the name "blackwater fever" and was the first to successfully treat such cases following the publication of his pamphlet.

Artemether is a medication used for the treatment of malaria. The injectable form is specifically used for severe malaria rather than quinine. In adults, it may not be as effective as artesunate. It is given by injection in a muscle. It is also available by mouth in combination with lumefantrine, known as artemether/lumefantrine.

Artesunate (AS) is a medication used to treat malaria. The intravenous form is preferred to quinine for severe malaria. Often it is used as part of combination therapy, such as artesunate plus mefloquine. It is not used for the prevention of malaria. Artesunate can be given by injection into a vein, injection into a muscle, by mouth, and by rectum.

Theodor Albrecht Edwin Klebs was a German-Swiss microbiologist. He is mainly known for his work on infectious diseases. His works paved the way for the beginning of modern bacteriology, and inspired Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch. He was the first to identify a bacterium that causes diphtheria, which was called Klebs–Loeffler bacterium. He was the father of physician Arnold Klebs.

Brigadier Sir Neil Hamilton Fairley, was an Australian physician, medical scientist, and army officer who was instrumental in saving thousands of Allied lives from malaria and other diseases.

The history of malaria extends from its prehistoric origin as a zoonotic disease in the primates of Africa through to the 21st century. A widespread and potentially lethal human infectious disease, at its peak malaria infested every continent except Antarctica. Its prevention and treatment have been targeted in science and medicine for hundreds of years. Since the discovery of the Plasmodium parasites which cause it, research attention has focused on their biology as well as that of the mosquitoes which transmit the parasites.

Carl Warburg, also known as Charles Warburg, was a physician and scientist. He was the inventor of 'Warburg's Tincture', a medicine well known in the 19th century for treating fevers, including malaria.

Project 523 is a code name for a 1967 secret military project of the People's Republic of China to find antimalarial medications. Named after the date the project launched, 23 May, it addressed malaria, an important threat in the Vietnam War. At the behest of Ho Chi Minh, Prime Minister of North Vietnam, Zhou Enlai, the Premier of the People's Republic of China, convinced Mao Zedong, Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, to start the mass project "to keep [the] allies' troops combat-ready", as the meeting minutes put it. More than 500 Chinese scientists were recruited. The project was divided into three streams. The one for investigating traditional Chinese medicine discovered and led to the development of a class of new antimalarial drugs called artemisinins. Launched during and lasting throughout the Cultural Revolution, Project 523 was officially terminated in 1981.

John S. Sappington (1776-1856) was an American physician known for developing a quinine pill to treat malarial and other fever diseases in the Missouri and Mississippi valleys, where the disease was widespread. He later used the pill to prevent malaria. Because he both manufactured and sold "Dr. Sappington's Anti-Fever Pills", he became wealthy from his bestseller.

Intermittent fever is a type or pattern of fever in which there is an interval where temperature is elevated for several hours followed by an interval when temperature drops back to normal. This type of fever usually occurs during the course of an infectious disease. Diagnosis of intermittent fever is frequently based on the clinical history but some biological tests like complete blood count and blood culture are also used. In addition radiological investigations like chest X-ray, abdominal ultrasonography can also be used in establishing diagnosis.

The malaria therapy is an archaic medical procedure of treating diseases using artificial injection of malaria parasites. It is a type of pyrotherapy by which high fever is induced to stop or eliminate symptoms of certain diseases. In malaria therapy, malarial parasites (Plasmodium) are specifically used to cause fever, and an elevated body temperature reduces the symptoms of or cure the diseases. As the primary disease is treated, the malaria is then cured using antimalarial drugs. The method was developed by Austrian physician Julius Wagner-Jauregg in 1917 for the treatment of neurosyphilis for which he received the 1927 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.