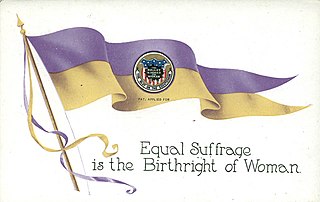

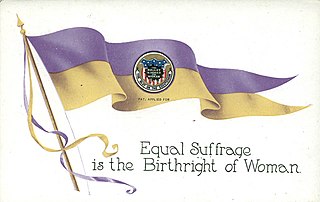

The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits the United States and its states from denying the right to vote to citizens of the United States on the basis of sex, in effect recognizing the right of women to vote. The amendment was the culmination of a decades-long movement for women's suffrage in the United States, at both the state and national levels, and was part of the worldwide movement towards women's suffrage and part of the wider women's rights movement. The first women's suffrage amendment was introduced in Congress in 1878. However, a suffrage amendment did not pass the House of Representatives until May 21, 1919, which was quickly followed by the Senate, on June 4, 1919. It was then submitted to the states for ratification, achieving the requisite 36 ratifications to secure adoption, and thereby go into effect, on August 18, 1920. The Nineteenth Amendment's adoption was certified on August 26, 1920.

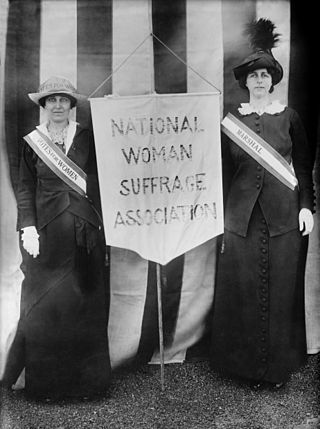

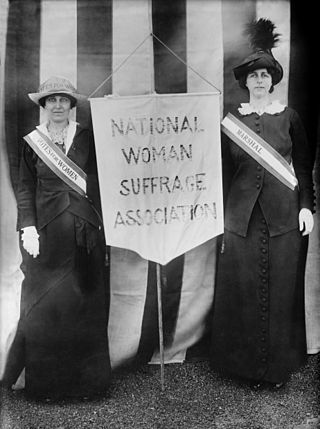

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was formed on May 15, 1869, to work for women's suffrage in the United States. Its main leaders were Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It was created after the women's rights movement split over the proposed Fifteenth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution, which would in effect extend voting rights to black men. One wing of the movement supported the amendment while the other, the wing that formed the NWSA, opposed it, insisting that voting rights be extended to all women and all African Americans at the same time.

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Its membership, which was about seven thousand at the time it was formed, eventually increased to two million, making it the largest voluntary organization in the nation. It played a pivotal role in the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which in 1920 guaranteed women's right to vote.

Women's suffrage, or the right to vote, was established in the United States over the course of more than half a century, first in various states and localities, sometimes on a limited basis, and then nationally in 1920 with the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution.

The Women's Freedom League was an organisation in the United Kingdom from 1907 to 1961 which campaigned for women's suffrage, pacifism and sexual equality. It was founded by former members of the Women's Social and Political Union after the Pankhursts decided to rule without democratic support from their members.

Zerelda Gray Sanders Wallace was the First Lady of Indiana from 1837 to 1840, and a temperance activist, women's suffrage leader, and inspirational speaker in the 1870s and 1880s. She was a charter member of Central Christian Church, the first Christian Church in Indianapolis, Indiana. Her husband was David Wallace, the sixth governor of Indiana; Lew Wallace, one of her stepsons, became an American Civil War general and author.

The history of human activity in Indiana, a U.S. state in the Midwest, stems back to the migratory tribes of Native Americans who inhabited Indiana as early as 8000 BC. Tribes succeeded one another in dominance for several thousand years and reached their peak of development during the period of Mississippian culture. The region entered recorded history in the 1670s, when the first Europeans came to Indiana and claimed the territory for the Kingdom of France. After France ruled for a century, it was defeated by Great Britain in the French and Indian War and ceded its territory east of the Mississippi River. Britain held the land for more than twenty years, until after its defeat in the American Revolutionary War, then ceded the entire trans-Allegheny region, including what is now Indiana, to the newly formed United States.

The Constitution of Indiana is the highest body of state law in the U.S. state of Indiana. It establishes the structure and function of the state and is based on the principles of federalism and Jacksonian democracy. Indiana's constitution is subordinate only to the U.S. Constitution and federal law. Prior to the enactment of Indiana's first state constitution and achievement of statehood in 1816, the Indiana Territory was governed by territorial law. The state's first constitution was created in 1816, after the U.S. Congress had agreed to grant statehood to the former Indiana Territory. The present-day document, which went into effect on November 1, 1851, is the state's second constitution. It supersedes Indiana's 1816 constitution and has had numerous amendments since its initial adoption.

This timeline highlights milestones in women's suffrage in the United States, particularly the right of women to vote in elections at federal and state levels.

Women's suffrage was established in the United States on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states, and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a member of Congress.

Grace Julian Clarke was a clubwoman, women's suffrage activist, newspaper journalist, and author from Indiana. As the daughter of George Washington Julian and the granddaughter of Joshua Reed Giddings, both of whom were abolitionists and members of the U.S. Congress, Clarke's family exposed her to social reform issues at an early age. She is credited with reviving the women's suffrage movement in Indiana, where she was especially active in the national campaign for women's suffrage in the early twentieth century. She is best known for founding and leading the Indiana State Federation of Women's Clubs, the Legislative Council, and the Women's Franchise League of Indiana. Clarke was the author of three books related to her father's life, and was a columnist for the Indianapolis Star from 1911 to 1929.

Helen M. Gougar was a lawyer, temperance and women's rights advocate, and newspaper journalist who resided in Lafayette, Indiana. Admitted to the Tippecanoe County, Indiana, bar in 1895 to present a "test" case, she was among the first women lawyers in the county. In 1897 she became one of the first women to argue a case before the Indiana Supreme Court. Gougar attracted attention for arguing a case for her right to vote in the 1894 elections. In addition to her advocacy work, Gougar became a public speaker and frequently campaigned to elect politicians who shared her views on women's suffrage and prohibition. She was the President for the Indiana Woman's Suffrage Association. An Indiana historical marker, dedicated in 2014, honors her efforts to secure voting rights for women.

Helen Colemen Benbridge (1876–1964) was an American suffragist, who was active in the Women's Right's Movement in Indiana in the early 20th century. Benbridge was elected president of The Women League of Voters in Vigo County, where she worked as an advocate for Hoosier women after the 19th amendment was passed in the United States.

Antoinette Dakin Leach was an American lawyer and a women's rights pioneer who was an active organizer on behalf of women's suffrage in Indiana. When the Greene-Sullivan Circuit Court denied Leach's petition for admission to the bar in 1893, her successful appeal to the Indiana Supreme Court, In re Petition of Leach, broke the gender barrier for admission to the bar in Indiana, securing the right for women to practice law in the state. The landmark decision, a progressive one for the time, also set a precedent that was used in 1897 as a test case to give Indiana women the right to vote, although the voting rights challenge in Gougar v Timberlake was unsuccessful. Leach was also an active politician and a supporter of women's suffrage who favored a constitutional amendment to secure women's right to vote.

Early women's suffrage work in Alabama started in the 1860s. Priscilla Holmes Drake was the driving force behind suffrage work until the 1890s. Several suffrage groups were formed, including a state suffrage group, the Alabama Woman Suffrage Organization (AWSO). The Alabama Constitution had a convention in 1901 and suffragists spoke and lobbied for women's rights provisions. However, the final constitution continued to exclude women. Women's suffrage efforts were mainly dormant until the 1910s when new suffrage groups were formed. Suffragists in Alabama worked to get a state amendment ratified and when this failed, got behind the push for a federal amendment. Alabama did not ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until 1953. For many years, both white women and African American women were disenfranchised by poll taxes. Black women had other barriers to voting including literacy tests and intimidation. Black women would not be able to fully access their right to vote until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The first women's suffrage effort in Florida was led by Ella C. Chamberlain in the early 1890s. Chamberlain began writing a women's suffrage news column, started a mixed-gender women's suffrage group and organized conventions in Florida.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Florida. Ella C. Chamberlain began women's suffrage efforts in Florida starting in 1892. However, after Chamberlain leaves the state in 1897, suffrage work largely ceases until the next century. More women's suffrage groups are organized, with the first in the twentieth century being the Equal Franchise League in Jacksonville, Florida in 1912. Additional groups are created around Florida, including a Men's Equal Suffrage League of Florida. Suffragists lobby the Florida Legislature for equal suffrage, hold conventions, and educate voters. Several cities in Florida pass laws allowing women to vote in municipal elections, with Fellsmere being the first in 1915. Zena Dreier becomes the first woman to legally cast a vote in the South on June 19, 1915. On May 26, 1919, women in Orlando vote for the first time. After the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, Helen Hunt West becomes the first woman in Florida to register to vote under equal franchise rules on September 7, 1920. Florida does not ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until May 13, 1969.

Ele Stansbury was an American lawyer and politician who served as the twenty-third Indiana Attorney General from January 1, 1917 to January 1, 1921.

Marie Stuart Edwards was a suffragist and social reformer from Peru, Indiana. She served as president of the Woman's Franchise League of Indiana (1917-1919); publicity director of National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) during the Nineteenth Amendment's passage in 1920; and vice president of the National League of Women Voters (1921-1923).

Carrie Whalon (1870-1927) was an African-American and Hoosier suffrage leader and the first President of the First Colored Women's Franchise League/First Colored Woman's Suffrage Club in Indianapolis. Her last name was also spelled as Whallon and Whalen in newspaper articles.