The Dominican Republic is a North American country on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with Haiti, making Hispaniola one of only two Caribbean islands, along with Saint Martin, that is shared by two sovereign states. It is the second-largest nation in the Antilles by area at 48,671 square kilometers (18,792 sq mi), and second-largest by population, with approximately 11.4 million people in 2024, of whom approximately 3.6 million live in the metropolitan area of Santo Domingo, the capital city.

The recorded history of the Dominican Republic began in 1492 when the Genoa-born navigator Christopher Columbus, working for the Crown of Castile, happened upon a large island in the region of the western Atlantic Ocean that later came to be known as the Caribbean. It was inhabited by the Taíno, an Arawakan people, who called the eastern part of the island Quisqueya (Kiskeya), meaning "mother of all lands." Columbus promptly claimed the island for the Spanish Crown, naming it La Isla Española, later Latinized to Hispaniola. After 25 years of Spanish occupation, the Taíno population in the Spanish-dominated parts of the island drastically decreased through genocide. With fewer than 50,000 remaining, the survivors intermixed with Spaniards, Africans, and others, forming the present-day tripartite Dominican population. What would become the Dominican Republic was the Spanish Captaincy General of Santo Domingo until 1821, except for a time as a French colony from 1795 to 1809. It was then part of a unified Hispaniola with Haiti from 1822 until 1844. In 1844, Dominican independence was proclaimed and the republic, which was often known as Santo Domingo until the early 20th century, maintained its independence except for a short Spanish occupation from 1861 to 1865 and occupation by the United States from 1916 to 1924.

Santo Domingo, once known as Santo Domingo de Guzmán, known as Ciudad Trujillo between 1936 and 1961, is the capital and largest city of the Dominican Republic and the largest metropolitan area in the Caribbean by population. As of 2022, the city and immediate surrounding area had a population of 1,029,110 while the total population is 3,798,699 when including Greater Santo Domingo. The city is coterminous with the boundaries of the Distrito Nacional, itself bordered on three sides by Santo Domingo Province.

Ramón Buenaventura Báez Méndez, was a Dominican conservative politician and military figure. He was president of the Dominican Republic for five nonconsecutive terms. His rule was characterized by corruption and governing for the benefit of his personal fortune.

Santo Domingo is a province of the Dominican Republic. It was split from the Distrito Nacional on October 16, 2001.

Juan Pablo Duarte y Díez was a Dominican military leader, writer, activist, and nationalist politician who was the foremost of the founding fathers of the Dominican Republic and bears the title of Father of the Nation. As one of the most celebrated figures in Dominican history, Duarte is considered a folk hero and revolutionary visionary in the modern Dominican Republic, who along with military generals Ramón Matías Mella and Francisco del Rosario Sánchez, organized and promoted La Trinitaria, a secret society that eventually led to the Dominican revolt and independence from Haitian rule in 1844 and the start of the Dominican War of Independence.

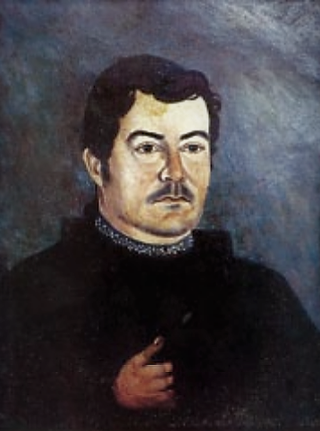

Francisco del Rosario Sánchez was a Dominican revolutionary, politician, and former president of the Dominican Republic. He is considered by Dominicans as the second prominent leader of the Dominican War of Independence, after Juan Pablo Duarte and before Matías Ramón Mella. Widely acknowledged as one of the founding fathers of the Dominican Republic, and the only martyr of the three, he is honored as a national hero. In addition, the Order of Merit of Duarte, Sánchez and Mella is named partially in his honor.

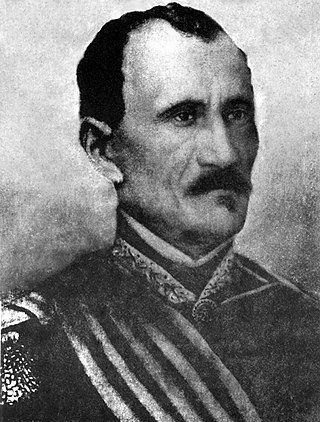

Pedro Santana y Familias, 1st Marquess of Las Carreras was a military commander and royalist politician who served as the president of the junta that had established the First Dominican Republic, a precursor to the position of the President of the Dominican Republic, and as the first President of the republic in the modern line of succession. A traditional royalist who was fond of the Monarchy of Spain and the Spanish Empire, he ruled as a governor-general, but effectively as an authoritarian dictator. During his life he enjoyed the title of "Libertador de la Patria." Aside from Juan Sánchez Ramírez, he was the only other Dominican head of state to serve as a governor to Santo Domingo.

Matías Ramón Mella Castillo, who was most known by his middle name (Ramón), was a Dominican revolutionary, politician, and military general. Mella is regarded as a national hero in the Dominican Republic. He is a hero of two glorious deeds in Dominican history: the proclamation of the First Republic, and the war to restore Dominican independence. Remembered as one of the three founding fathers of the Dominican Republic, the Order of Merit of Duarte, Sánchez and Mella is partially named in his honor.

The Republic of Spanish Haiti, also called the Independent State of Spanish Haiti was the independent state that succeeded the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo after independence was declared on November 30, 1821 by José Núñez de Cáceres. The republic lasted only from December 1, 1821 to February 9, 1822 when it was invaded by the Republic of Haiti.

The 2003 Pan American Games were held in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, from August 1 to 17, 2003. The successful bid for the Games was made in the mid-1990s, when Dominican Republic had one of the highest growth rates in Latin America.

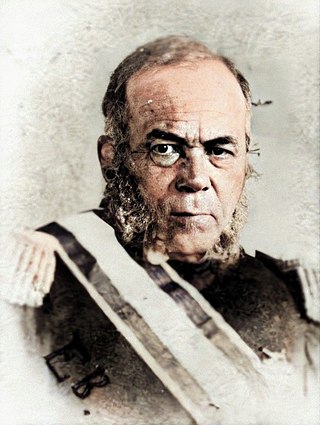

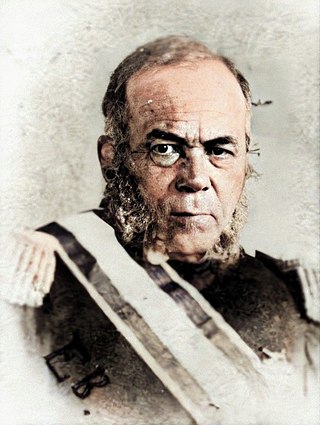

Gregorio Luperón was a Dominican revolutionary, military general, businessman, liberal politician, freemason, and Statesman who was one of the leaders in the Dominican Restoration War. Luperón was an active member of the Triunvirato of 1866, becoming the President of the Provincial Government in San Felipe de Puerto Plata, and after the successful coup against Cesareo Guillermo, he became the 20th President of the Dominican Republic.

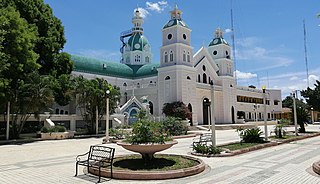

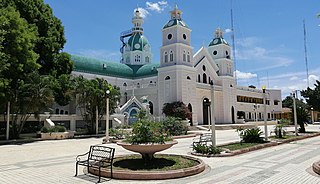

San Juan de la Maguana is a city and municipality in the western region of the Dominican Republic and capital of the San Juan province. It was one of the first cities established on the island; founded in 1503, and was given the name of San Juan de la Maguana by San Juan Bautista and the Taino name of the valley: Maguana. The term Maguana means "the first stone, the unique stone".

The Dominican Restoration War or the Dominican War of Restoration was a guerrilla war between 1863 and 1865 in the Dominican Republic between nationalists and Spain, the latter of which had recolonized the country 17 years after its independence. The war resulted in the restoration of Dominican sovereignty, the withdrawal of Spanish forces, the separation of the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo from Spain, and the establishment of a second republic in the Dominican Republic.

Dominican Republic–United States relations are bilateral relations between the Dominican Republic and the United States of America. There are around 200,000 Americans expats in the Dominican Republic, and a little over 2 million Dominicans live in the United States.

The Haitian occupation of Santo Domingo was the annexation and merger of then-independent Republic of Spanish Haiti into the Republic of Haiti, that lasted twenty-two years, from February 9, 1822, to February 27, 1844. The part of Hispaniola under Spanish administration was first ceded to France and merged with the French colony of Saint Domingue as a result of the Peace of Basel in 1795. However, with the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution the French lost the western part of the island, while remaining in control of the eastern part of the island until the Spanish recaptured Santo Domingo in 1809.

General José María Cabral y Luna was a Dominican military figure and politician. He served as the first Supreme Chief of the Dominican Republic from August 4, 1865, to November 15 of that year and again officially as president from August 22, 1866, until January 3, 1868.

Fernando Arturo de Meriño y Ramírez was a Dominican priest and politician. He served as President of the Dominican Republic from September 1, 1880, until September 1, 1882. He served as the President of Chamber of Deputies of the Dominican Republic in 1878 and 1883. He was later made an archbishop.

The proposed annexation of Santo Domingo was an attempted treaty during the later Reconstruction era, initiated by United States President Ulysses S. Grant in 1869, to annex Santo Domingo as a United States territory, with the promise of eventual statehood. President Grant feared some European power would take the island country in violation of the Monroe Doctrine. He privately thought annexation would be a safety valve for African Americans who were suffering persecution in the U.S., but he did not include this in his official messages. Grant speculated that the acquisition of Santo Domingo would help bring about the end of slavery in Cuba and elsewhere.

Dominican Republic–Spain relations are the bilateral relations between the Dominican Republic and Spain. Both nations are members of the Association of Academies of the Spanish Language and the Organization of Ibero-American States.