Eugenics is a set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or promoting those judged to be superior. In recent years, the term has seen a revival in bioethical discussions on the usage of new technologies such as CRISPR and genetic screening, with heated debate around whether these technologies should be considered eugenics or not.

Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927), is a decision of the United States Supreme Court, written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., in which the Court ruled that a state statute permitting compulsory sterilization of the unfit, including the intellectually disabled, "for the protection and health of the state" did not violate the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Despite the changing attitudes in the coming decades regarding sterilization, the Supreme Court has never expressly overturned Buck v. Bell. It is widely believed to have been weakened by Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942), which involved compulsory sterilization of male habitual criminals. Legal scholar and Holmes biographer G. Edward White, in fact, wrote, "the Supreme Court has distinguished the case [Buck v. Bell] out of existence". In addition, federal statutes, including the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, provide protections for people with disabilities, defined as both physical and mental impairments.

Madison Grant was an American lawyer, zoologist, anthropologist, and writer known for his work as a conservationist, eugenicist, and advocate of scientific racism. Grant is less noted for his far-reaching achievements in conservation than for his advocacy of Nordicism, a form of racism which views the "Nordic race" as superior.

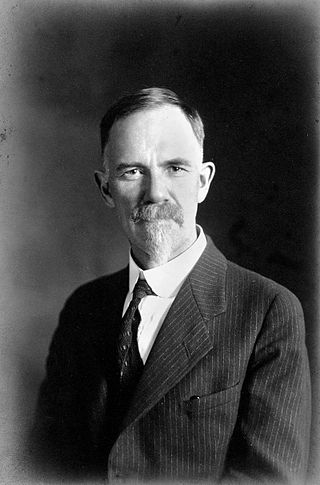

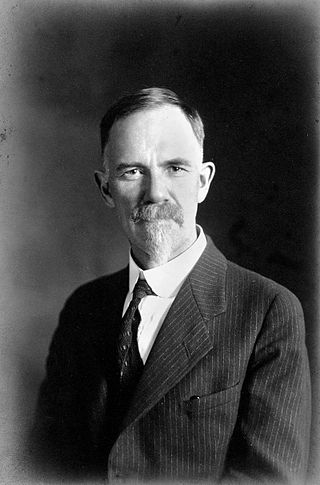

Paul Bowman Popenoe was an American marriage counselor, eugenicist and agricultural explorer. He was an influential advocate of the compulsory sterilization of mentally ill people and people with mental disabilities, and the father of marriage counseling in the United States.

In 1924, the Virginia General Assembly enacted the Racial Integrity Act. The act reinforced racial segregation by prohibiting interracial marriage and classifying as "white" a person "who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian." The act, an outgrowth of eugenist and scientific racist propaganda, was pushed by Walter Plecker, a white supremacist and eugenist who held the post of registrar of Virginia Bureau of Vital Statistics.

Harry Hamilton Laughlin was an American educator and eugenicist. He served as the superintendent of the Eugenics Record Office from its inception in 1910 to its closure in 1939, and was among the most active individuals influencing American eugenics policy, especially compulsory sterilization legislation.

Charles Benedict Davenport was a biologist and eugenicist influential in the American eugenics movement.

The Society for Biodemography and Social Biology, formerly known as the Society for the Study of Social Biology and before then as the American Eugenics Society, was the society dedicated to "furthering the discussion, advancement, and dissemination of knowledge about biological and sociocultural forces which affect the structure and composition of human populations." The Society was disbanded in 2019.

The Adelphi Genetics Forum is a non-profit learned society based in the United Kingdom. Its aims are "to promote the public understanding of human heredity and to facilitate informed debate about the ethical issues raised by advances in reproductive technology."

Eugenics has influenced political, public health and social movements in Japan since the late 19th and early 20th century. Originally brought to Japan through the United States, through Mendelian inheritance by way of German influences, and French Lamarckian eugenic written studies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Eugenics as a science was hotly debated at the beginning of the 20th, in Jinsei-Der Mensch, the first eugenics journal in the Empire. As the Japanese sought to close ranks with the West, this practice was adopted wholesale, along with colonialism and its justifications.

Nazi eugenics refers to the social policies of eugenics in Nazi Germany, composed of various ideas about genetics which are now considered pseudoscientific. The racial ideology of Nazism placed the biological improvement of the German people by selective breeding of "Nordic" or "Aryan" traits at its center. These policies were used to justify the involuntary sterilization and mass-murder of those deemed "undesirable".

Three International Eugenics Congresses took place between 1912 and 1932 and were the global venue for scientists, politicians, and social leaders to plan and discuss the application of programs to improve human heredity in the early twentieth century.

Morris Steggerda was an American physical anthropologist. He worked primarily on Central American and Caribbean populations.

Eugenics, the set of beliefs and practices which aims at improving the genetic quality of the human population, played a significant role in the history and culture of the United States from the late 19th century into the mid-20th century. The cause became increasingly promoted by intellectuals of the Progressive Era.

The International Federation of Eugenic Organizations (IFEO) was an international organization of groups and individuals focused on eugenics. Founded in London in 1912, where it was originally titled the Permanent International Eugenics Committee, it was an outgrowth of the first International Eugenics Congress. In 1925, it was retitled. Factionalism within the organization led to its division in 1933, as splinter group the Latin International Federation of Eugenics Organizations was created to give a home to eugenicists who disliked the concepts of negative eugenics, in which unfit groups and individuals are discouraged or prevented from reproducing. As the views of the Nazi party in Germany caused increasing tension within the group and leadership activity declined, it dissolved in the latter half of the 1930s.

Geza von Hoffmann (1885–1921) was a prominent Austrian-Hungarian eugenicist and writer. He lived for a time in California as the Austrian Vice-Consulate where he observed and wrote on eugenics practices in the United States.

The history of eugenics is the study of development and advocacy of ideas related to eugenics around the world. Early eugenic ideas were discussed in Ancient Greece and Rome. The height of the modern eugenics movement came in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Gertrude Anna Davenport, was an American zoologist who worked as both a researcher and an instructor at established research centers such as the University of Kansas and the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory where she studied embryology, development, and heredity. The wife of Charles Benedict Davenport, a prominent eugenicist, she co-authored several works with her husband. Together, they were highly influential in the United States eugenics movement during the progressive era.

Following the Mexican Revolution, the eugenics movement gained prominence in Mexico. Seeking to change the genetic make-up of the country's population, proponents of eugenics in Mexico focused primarily on rebuilding the population, creating healthy citizens, and ameliorating the effects of perceived social ills such as alcoholism, prostitution, and venereal diseases. Mexican eugenics, at its height in the 1930s, influenced the state's health, education, and welfare policies.

The Race Betterment Foundation was a eugenics and racial hygiene organization founded in 1914 at Battle Creek, Michigan by John Harvey Kellogg due to his concerns about what he perceived as "race degeneracy". The foundation supported conferences, publications, and the formation of a eugenics registry in cooperation with the ERO. The foundation also sponsored the Fitter Families Campaign from 1928 to the late 1930s and funded Battle Creek College. The foundation controlled the Battle Creek Food Company, which in turn served as the major source for Kellogg's eugenics programs, conferences, and Battle Creek College. In his will, Kellogg left his entire estate to the foundation. In 1947, the foundation had over $687,000 in assets. By 1967, the foundation's accounts were a mere $492.87. In 1967, the state of Michigan indicted the trustees for squandering the foundation's funds and the foundation closed.