A chemical structure determination includes a chemist's specifying the molecular geometry and, when feasible and necessary, the electronic structure of the target molecule or other solid. Molecular geometry refers to the spatial arrangement of atoms in a molecule and the chemical bonds that hold the atoms together, and can be represented using structural formulae and by molecular models; complete electronic structure descriptions include specifying the occupation of a molecule's molecular orbitals. Structure determination can be applied to a range of targets from very simple molecules, to very complex ones.

Molecular geometry is the three-dimensional arrangement of the atoms that constitute a molecule. It includes the general shape of the molecule as well as bond lengths, bond angles, torsional angles and any other geometrical parameters that determine the position of each atom.

Valence shell electron pair repulsion (VSEPR) theory is a model used in chemistry to predict the geometry of individual molecules from the number of electron pairs surrounding their central atoms. It is also named the Gillespie-Nyholm theory after its two main developers, Ronald Gillespie and Ronald Nyholm. The acronym "VSEPR" is pronounced either "ves-pur" or "vuh-seh-per".

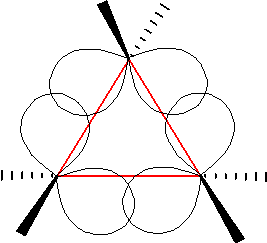

In chemistry, orbital hybridisation is the concept of mixing atomic orbitals into new hybrid orbitals suitable for the pairing of electrons to form chemical bonds in valence bond theory. Hybrid orbitals are very useful in the explanation of molecular geometry and atomic bonding properties and are symmetrically disposed in space. Although sometimes taught together with the valence shell electron-pair repulsion (VSEPR) theory, valence bond and hybridisation are in fact not related to the VSEPR model.

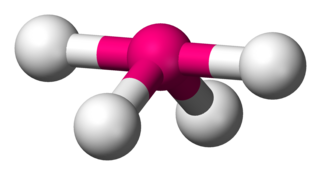

In chemistry, a trigonal pyramid is a molecular geometry with one atom at the apex and three atoms at the corners of a trigonal base, resembling a tetrahedron (not to be confused with the tetrahedral geometry). When all three atoms at the corners are identical, the molecule belongs to point group C3v. Some molecules and ions with trigonal pyramidal geometry are the pnictogen hydrides (XH3), xenon trioxide (XeO3), the chlorate ion, ClO−

3, and the sulfite ion, SO2−

3. In organic chemistry, molecules which have a trigonal pyramidal geometry are sometimes described as sp3 hybridized. The AXE method for VSEPR theory states that the classification is AX3E1.

In chemistry, trigonal planar is a molecular geometry model with one atom at the center and three atoms at the corners of an equilateral triangle, called peripheral atoms, all in one plane. In an ideal trigonal planar species, all three ligands are identical and all bond angles are 120°. Such species belong to the point group D3h. Molecules where the three ligands are not identical, such as H2CO, deviate from this idealized geometry. Examples of molecules with trigonal planar geometry include boron trifluoride (BF3), formaldehyde (H2CO), phosgene (COCl2), and sulfur trioxide (SO3). Some ions with trigonal planar geometry include nitrate (NO−

3), carbonate (CO2−

3), and guanidinium (C(NH

2)+

3). In organic chemistry, planar, three-connected carbon centers that are trigonal planar are often described as having sp2 hybridization.

In chemistry a trigonal bipyramid formation is a molecular geometry with one atom at the center and 5 more atoms at the corners of a triangular bipyramid. This is one geometry for which the bond angles surrounding the central atom are not identical (see also pentagonal bipyramid), because there is no geometrical arrangement with five terminal atoms in equivalent positions. Examples of this molecular geometry are phosphorus pentafluoride (PF5), and phosphorus pentachloride (PCl5) in the gas phase.

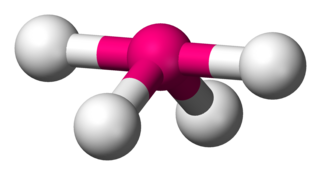

In a tetrahedral molecular geometry, a central atom is located at the center with four substituents that are located at the corners of a tetrahedron. The bond angles are cos−1(−⅓) = 109.4712206...° ≈ 109.5° when all four substituents are the same, as in methane (CH4) as well as its heavier analogues. Methane and other perfectly symmetrical tetrahedral molecules belong to point group Td, but most tetrahedral molecules have lower symmetry. Tetrahedral molecules can be chiral.

In chemistry, Bent's rule describes and explains the relationship between the orbital hybridization of central atoms in molecules and the electronegativities of substituents. The rule was stated by Henry Bent as follows:

Nitrite reductase refers to any of several classes of enzymes that catalyze the reduction of nitrite. There are two classes of NIR's. A multi haem enzyme reduces NO2− to a variety of products. Copper containing enzymes carry out a single electron transfer to produce nitric oxide.

Disphenoidal or Seesaw is a type of molecular geometry where there are four bonds to a central atom with overall C2v symmetry. The name "seesaw" comes from the observation that it looks like a playground seesaw. Most commonly, four bonds to a central atom result in tetrahedral or, less commonly, square planar geometry. The seesaw geometry, just like its name, is unusual.

In chemistry, the linear molecular geometry describes the geometry around a central atom bonded to two other atoms placed at a bond-angle of 180°. Linear organic molecules, such as acetylene (HC≡CH), are often described by invoking sp orbital hybridization for their carbon centers.

A chemical bonding model is a theoretical model used to explain atomic bonding structure, molecular geometry, properties, and reactivity of physical matter. This can refer to:

Disilyne, Si

2H

2, is a metalloid hydride composed of silicon and hydrogen. Disilyne is not well-characterised, and it is kinetically unstable with respect to isomerisation. The most stable isomer is a dibridged singlet, named di-μH-disilyne, followed by a monobridged μH-disilyne. A third, unbridged singlet ismomer is predicted to exist before disilyne - disilenylidene.

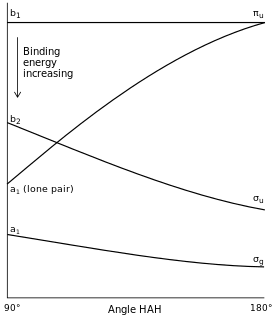

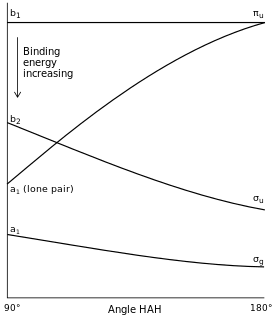

Walsh diagrams, often called angular coordinate diagrams or correlation diagrams, are representations of calculated orbital binding energies of a molecule versus a distortion coordinate, used for making quick predictions about the geometries of small molecules. By plotting the change in molecular orbital levels of a molecule as a function of geometrical change, Walsh diagrams explain why molecules are more stable in certain spatial configurations.

In chemistry, topology provides a convenient way of describing and predicting the molecular structure within the constraints of three-dimensional (3-D) space. Given the determinants of chemical bonding and the chemical properties of the atoms, topology provides a model for explaining how the atoms ethereal wave functions must fit together. Molecular topology is a part of mathematical chemistry dealing with the algebraic description of chemical compounds so allowing a unique and easy characterization of them.

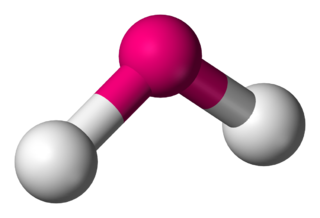

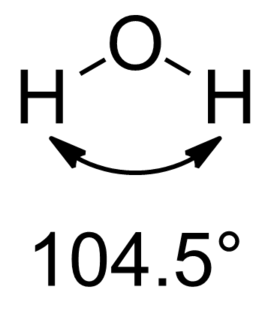

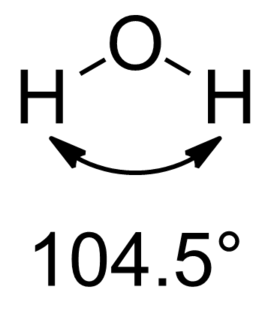

Water is a simple triatomic bent molecule with C2v molecular symmetry and bond angle of 104.5° between the central oxygen atom and the hydrogen atoms. Despite being one of the simplest triatomic molecules, its chemical bonding scheme is nonetheless complex as many of its bonding properties such as bond angle, ionization energy, and electronic state energy cannot be explained by one unified bonding model. Instead, several traditional and advanced bonding models such as simple Lewis and VESPR structure, valence bond theory, molecular orbital theory, isovalent hybridization, and Bent's rule are discussed below to provide a comprehensive bonding model for H

2O, explaining and rationalizing the various electronic and physical properties and features manifested by its peculiar bonding arrangements.