Related Research Articles

The Final Solution or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question was a Nazi plan for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews during World War II. The "Final Solution to the Jewish question" was the official code name for the murder of all Jews within reach, which was not restricted to the European continent. This policy of deliberate and systematic genocide starting across German-occupied Europe was formulated in procedural and geopolitical terms by Nazi leadership in January 1942 at the Wannsee Conference held near Berlin, and culminated in the Holocaust, which saw the murder of 90% of Polish Jews, and two-thirds of the Jewish population of Europe. The Final Solution did not, however, include the hundreds of thousands of Jews killed by Romanian forces. By far the greatest extermination of Jews by non-German forces, this genocide was "operationally separate from the Nazi Final Solution".

Paul Joseph Goebbels was a German philologist and Nazi politician who was the Gauleiter of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 1945. He was one of Adolf Hitler's closest and most devoted followers, known for his skills in public speaking and his deeply virulent antisemitism which was evident in his publicly voiced views. He advocated progressively harsher discrimination, including the extermination of the Jews in the Holocaust.

Mein Kampf is a 1925 autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The work describes the process by which Hitler became antisemitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for Germany. Volume 1 of Mein Kampf was published in 1925 and Volume 2 in 1926. The book was edited first by Emil Maurice, then by Hitler's deputy Rudolf Hess.

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich until 1943, later the Greater German Reich, was the German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictatorship.

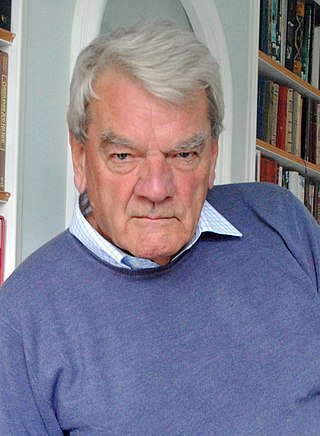

David John Cawdell Irving is an English author and Holocaust denier who has written on the military and political history of World War II, with a focus on Nazi Germany. His works include The Destruction of Dresden (1963), Hitler's War (1977), Churchill's War (1987) and Goebbels: Mastermind of the Third Reich (1996). In his works, he argued that Adolf Hitler did not know of the extermination of Jews, or, if he did, he opposed it. Though Irving's negationist claims and views of German war crimes in World War II were never taken seriously by mainstream historians, he was once recognised for his knowledge of Nazi Germany and his ability to unearth new historical documents.

Der Stürmer was a weekly German tabloid-format newspaper published from 1923 to the end of World War II by Julius Streicher, the Gauleiter of Franconia, with brief suspensions in publication due to legal difficulties. It was a significant part of Nazi propaganda, and was virulently anti-Semitic. The paper was not an official publication of the Nazi Party, but was published privately by Streicher. For this reason, the paper did not display the Nazi Party swastika in its logo.

Heinrich Müller was a high-ranking German Schutzstaffel (SS) and police official during the Nazi era. For most of World War II in Europe, he was the chief of the Gestapo, the secret state police of Nazi Germany. Müller was central in the planning and execution of the Holocaust and attended the January 1942 Wannsee Conference, which formalised plans for deportation and genocide of all Jews in German-occupied Europe—The "Final Solution to the Jewish Question". He was known as "Gestapo Müller" to distinguish him from another SS general named Heinrich Müller.

Jacob Otto Dietrich was a German SS officer during the Nazi era, who served as the Press Chief of the Nazi regime and was a confidant of Adolf Hitler.

The Destruction of the European Jews is a 1961 book by historian Raul Hilberg. Hilberg revised his work in 1985, and it appeared in a new three-volume edition. It is largely held to be the first comprehensive historical study of the Holocaust. According to Holocaust historian, Michael R. Marrus, until the book appeared, little information about the genocide of the Jews by Nazi Germany had "reached the wider public" in both the West and the East, and even in pertinent scholarly studies it was "scarcely mentioned or only mentioned in passing as one more atrocity in a particularly cruel war".

Lucy Dawidowicz was an American historian and writer. She wrote books about modern Jewish history, in particular, about the Holocaust.

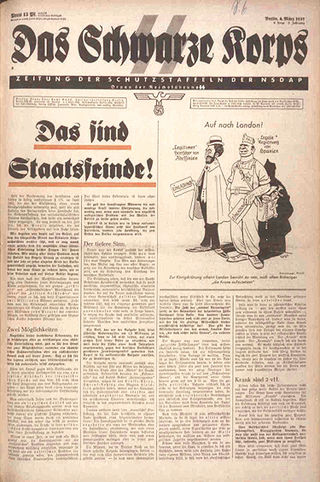

Das Schwarze Korps was the official newspaper of the Schutzstaffel (SS). This newspaper was published on Wednesdays and distributed free of charge. All SS members were encouraged to read it. The chief editor was SS leader Gunter d'Alquen; the publisher was Max Amann of the Franz-Eher-Verlag publishing company. The paper was hostile to many groups, with frequent articles condemning the Catholic Church, Jews, Communism, Freemasonry, and others.

The Meaning of Hitler is a 1978 book by the journalist and writer Raimund Pretzel, who published all his books under the pseudonym Sebastian Haffner. Journalist and military historian Sir Max Hastings called it 'among the best' studies of Hitler; Edward Crankshaw called it a 'quite dazzlingly brilliant analysis'.

The propaganda used by the German Nazi Party in the years leading up to and during Adolf Hitler's dictatorship of Germany from 1933 to 1945 was a crucial instrument for acquiring and maintaining power, and for the implementation of Nazi policies.

Hitler's War is a biographical book by British author David Irving. It describes the Second World War from the point of view of Nazi Germany’s leader Adolf Hitler.

Roger Moorhouse is a British historian and author.

The relationship between Nazi Germany (1933–1945) and the leadership of the Arab world encompassed contempt, propaganda, collaboration, and in some instances emulation. Cooperative political and military relationships were founded on shared hostilities toward common enemies, such as the United Kingdom and the French Third Republic, along with communism, and Zionism.

This is a list of books about Nazi Germany, the state that existed in Germany during the period from 1933 to 1945, when its government was controlled by Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist German Workers' Party. It also includes some important works on the development of Nazi imperial ideology, totalitarianism, German society during the era, the formation of anti-Semitic racial policies, the post-war ramifications of Nazism, along with various conceptual interpretations of the Third Reich.

During a speech at the Reichstag on 30 January 1939, Adolf Hitler threatened "the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe" in the event of war:

If international finance Jewry inside and outside Europe should succeed in plunging the nations once more into a world war, the result will be not the Bolshevization of the earth and thereby the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe.

On 30 January 1939, Nazi German dictator Adolf Hitler gave a speech in the Kroll Opera House to the Reichstag delegates, which is best known for the prediction he made that "the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe" would ensue if another world war were to occur.

The claim that there was a Jewish war against Nazi Germany is an antisemitic conspiracy theory promoted in Nazi propaganda which asserts that the Jews, framed within the theory as a single historical actor, started World War II and sought the destruction of Germany. Alleging that war was declared in 1939 by Chaim Weizmann, president of the World Zionist Organization, Nazis used this false notion to justify the persecution of Jews under German control on the grounds that the Holocaust was justified self-defense. Since the end of World War II, the conspiracy theory has been popular among neo-Nazis and Holocaust deniers.

References

- 1 2 Roberts, Andrew (6 August 2010). "Berlin at War". Financial Times. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ Moorhouse, Roger (2010). Berlin at War. New York, NY: Basic Books. pp. 174–175. ISBN 978-0-465-00533-8.

- ↑ Thomson, Ian (8 August 2010). "Berlin at War by Roger Moorhouse: review". The Telegraph. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ "Berlin at War". Kirkus Reviews . 23 June 2010. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ↑ Rule, Vera (6 September 2011). "Berlin at War by Roger Moorhouse – review". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ Schüler, C. J. (19 August 2010). "Berlin at War: Life and Death in Hitler's Capital, 1939-45, By Roger Moorhouse". The Independent. Retrieved 24 May 2022.