Chicano or Chicana is an ethnic identity for Mexican Americans who have a non-Anglo self-image, embracing their Mexican Native ancestry. Chicano was originally a classist and racist slur used toward low-income Mexicans that was reclaimed in the 1940s among youth who belonged to the Pachuco and Pachuca subculture. In the 1960s, Chicano was widely reclaimed in the building of a movement toward political empowerment, ethnic solidarity, and pride in being of indigenous descent. Chicano developed its own meaning separate from Mexican American identity. Youth in barrios rejected cultural assimilation into whiteness and embraced their own identity and worldview as a form of empowerment and resistance. The community forged an independent political and cultural movement, sometimes working alongside the Black power movement.

M.E.Ch.A. is a US-based organization that seeks to promote Chicano unity and empowerment through political action. The acronym of the organization's name is the Chicano word mecha, which is the Chicano pronunciation of the English word match and therefore symbolic of a fire or spark; mecha in Spanish means fuse or wick. The motto of MEChA is 'La Union Hace La Fuerza'.

José Montoya was a poet and an artist from Sacramento, California. He was one of the most influential Chicano bilingual poets. He has published many well-known poems in anthologies and magazines, and served as Sacramento's poet laureate.

El Plan de Santa Bárbara: A Chicano Plan for Higher Education is a 155-page document, which was written in 1969 by the Chicano Coordinating Council on Higher Education. Drafted at the University of California Santa Barbara, it is a blueprint for the inception of Chicana/o studies programs in colleges and universities throughout the US. The Chicano Coordinating Council expresses political mobilization to be dependent upon political consciousness, thus the institution of education is targeted as the platform to raise political conscious amongst Chicanos and spur higher learning to political action. The Plan proposes a curriculum in Chicano studies, the role of community control in Chicano education and the necessity of Chicano political independence. The document was a framework for educational and curriculum goals for the Chicano movements within the institution of education, while being the foundation for the Chicano student group Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA).

Ethnic studies, in the United States, is the interdisciplinary study of difference—chiefly race, ethnicity, and nation, but also sexuality, gender, and other such markings—and power, as expressed by the state, by civil society, and by individuals.

Latino studies is an academic discipline which studies the experience of people of Latin American ancestry in the United States. Closely related to other ethnic studies disciplines such as African-American studies, Asian American studies, and Native American studies, Latino studies critically examines the history, culture, politics, issues, sociology, spirituality (Indigenous) and experiences of Latino people. Drawing from numerous disciplines such as sociology, history, literature, political science, religious studies and gender studies, Latino studies scholars consider a variety of perspectives and employ diverse analytical tools in their work.

The Brown Berets is a pro-Chicano paramilitary organization that emerged during the Chicano Movement in the late 1960s. David Sanchez and Carlos Montes co-founded the group modeled after the Black Panther Party. The Brown Berets was part of the Third World Liberation Front. It worked for educational reform, farmworkers' rights, and against police brutality and the Vietnam War. It also sought to separate the American Southwest from the control of the United States government.

Chicanismo emerged as the cultural consciousness behind the Chicano Movement. The central aspect of Chicanismo is the identification of Chicanos with their Indigenous American roots to create an affinity with the notion that they are native to the land rather than immigrants. Chicanismo brought a new sense of nationalism for Chicanos that extended the notion of family to all Chicano people. Barrios, or working-class neighborhoods, became the cultural hubs for the people. It created a symbolic connection to the ancestral ties of Mesoamerica and the Nahuatl language through the situating of Aztlán, the ancestral home of the Aztecs, in the southwestern United States. Chicanismo also rejected Americanization and assimilation as a form of cultural destruction of the Chicano people, fostering notions of Brown Pride. Xicanisma has been referred to as an extension of Chicanismo.

Norma Elia Cantú is a Chicana postmodernist writer and the Murchison Professor in the Humanities at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas.

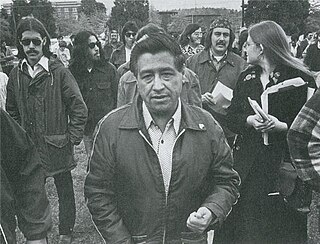

The Chicano Movement, also referred to as El Movimiento, was a social and political movement in the United States that worked to embrace a Chicano/a identity and worldview that combated structural racism, encouraged cultural revitalization, and achieved community empowerment by rejecting assimilation. Chicanos also expressed solidarity and defined their culture through the development of Chicano art during El Movimiento, and stood firm in preserving their religion.

Chicano poetry is a subgenre of Chicano literature that stems from the cultural consciousness developed in the Chicano Movement. Chicano poetry has its roots in the reclamation of Chicana/o as an identity of empowerment rather than denigration. As a literary field, Chicano poetry emerged in the 1960s and formed its own independent literary current and voice.

Rodolfo "Rudy" Francisco Acuña is an American historian, professor emeritus at California State University, Northridge, and a scholar of Chicano studies. He authored the 1972 book Occupied America: A History of Chicanos, approaching history of the Southwestern United States with a heavy emphasis on Mexican Americans. An eighth edition was published in 2014. Acuña has also written for the Los Angeles Times,The Los Angeles Herald-Express, La Opinión, and numerous other newspapers. His work emphasizes the struggles of Mexican American people. Acuña is an activist and he has supported numerous causes of the Chicano Movement. He currently teaches an on-line history course at California State University, Northridge.

Juan Gómez-Quiñones was an American historian, professor of history, poet, and activist. He was best known for his work in the field of Chicana/o history. As a co-editor of the Plan de Santa Bárbara, an educational manifesto for the implementation of Chicano studies programs in universities nationwide, he was an influential figure in the development of the field.

The National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies (NACCS) is "the academic organization that serves academic programs, departments and research centers that focus on issues pertaining to Mexican Americans, Chicana/os, and Latina/os." Unlike many professional academic associations, NACCS "rejects mainstream research, which promotes an integrationist perspective that emphasizes consensus, assimilation, and legitimization of societal institutions. NACCS promotes research that directly confronts structures of inequality based on class, race and gender privileges in U.S. society." The association is based in San Jose, California.

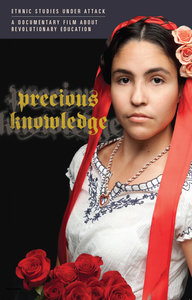

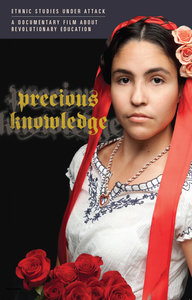

Precious Knowledge is a 2011 educational and political documentary that centers on the banning of the Mexican-American Studies (MAS) Program in the Tucson Unified School District of Arizona. The documentary was directed by Ari Luis Palos and produced by Eren Isabel McGinnis, the founders of Dos Vatos Productions.

This is a Mexican American bibliography. This list consists of books, and journal articles, about Mexican Americans, Chicanos, and their history and culture. The list includes works of literature whose subject matter is significantly about Mexican Americans and the Chicano/a experience. This list does not include works by Mexican American writers which do not address the topic, such as science texts by Mexican American writers.

The Mexican American Studies Department Programs (MAS) provide courses for students attending various elementary, middle, and high schools within the Tucson Unified School District (TUSD). Some key components of the MAS program include student support, curriculum content, teacher professional development, and parent and community involvement. In the past, programs helped Chicana/o and Latina/o students graduate, pursue higher education, and score higher test scores. A study found that "100 percent of those students enrolled in Mexican-American studies classes at Tucson High were graduating, and 85 percent were going on to college."

Patricia Zavella is an anthropologist and professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz in the Latin American and Latino Studies department. She has spent a career advancing Latina and Chicana feminism through her scholarship, teaching, and activism. She was president of the Association of Latina and Latino Anthropologists and has served on the executive board of the American Anthropological Association. In 2016, Zavella received the American Anthropological Association's award from the Committee on Gender Equity in Anthropology to recognize her career studying gender discrimination. The awards committee said Zavella’s career accomplishments advancing the status of women, and especially Latina and Chicana women have been exceptional. She has made critical contributions to understanding how gender, race, nation, and class intersect in specific contexts through her scholarship, teaching, advocacy, and mentorship. Zavella’s research focuses on migration, gender and health in Latina/o communities, Latino families in transition, feminist studies, and ethnographic research methods. She has worked on many collaborative projects, including an ongoing partnership with Xóchitl Castañeda where she wrote four articles some were in English and others in Spanish. The Society for the Anthropology of North America awarded Zavella the Distinguished Career Achievement in the Critical Study of North America Award in the year 2010. She has published many books including, most recently, "I'm Neither Here Nor There, Mexicans"Quotidian Struggles with Migration and Poverty, which focuses on working class Mexican Americans struggle for agency and identity in Santa Cruz County.

Mary Romero is an American sociologist. She is Professor of Justice Studies and Social Inquiry at Arizona State University, with affiliations in African and African American Studies, Women and Gender Studies, and Asian Pacific American Studies. Before her arrival at ASU in 1995, she taught at University of Oregon, San Francisco State University, and University of Wisconsin-Parkside. Professor Romero holds a bachelor's degree in sociology with a minor in Spanish from Regis College in Denver, Colorado. She holds a PhD in sociology from the University of Colorado. In 2019, she served as the 110th President of the American Sociological Association.

Pensamiento Serpentino is a poem by Chicano playwright Luis Valdez originally published by Cucaracha Publications, which was part of El Teatro Campesino, in 1973. The poem famously draws on philosophical concepts held by the Mayan people known as In Lak'ech, meaning "you are the other me." The poem also draws, although less prominently, on Aztec traditions, such as through the appearance of Quetzalcoatl. The poem received national attention after it was illegally banned as part of the removal of Mexican American Studies Programs in Tucson Unified School District. The ban was later ruled unconstitutional.