Related Research Articles

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables, to the Corpus Juris Civilis ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Justinian I. Roman law forms the basic framework for civil law, the most widely used legal system today, and the terms are sometimes used synonymously. The historical importance of Roman law is reflected by the continued use of Latin legal terminology in many legal systems influenced by it, including common law.

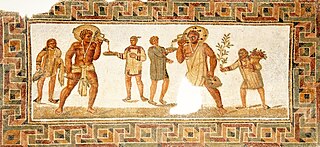

Commerce is the large-scale organized system of activities, functions, procedures and institutions that directly or indirectly contribute to the smooth, unhindered distribution and transfer of goods and services on a substantial scale and at the right time, place, quantity, quality and price through various channels from the original producers to the final consumers within local, regional, national or international economies. The diversity in the distribution of natural resources, differences of human needs and wants, and division of labour along with comparative advantage are the principal factors that give rise to commercial exchanges.

The pater familias, also written as paterfamilias, was the head of a Roman family. The pater familias was the oldest living male in a household, and could legally exercise autocratic authority over his extended family. The term is Latin for "father of the family" or the "owner of the family estate". The form is archaic in Latin, preserving the old genitive ending in -ās, whereas in classical Latin the normal first declension genitive singular ending was -ae. The pater familias always had to be a Roman citizen.

Public law is the part of law that governs relations and affairs between legal persons and a government, between different institutions within a state, between different branches of governments, as well as relationships between persons that are of direct concern to society. Public law comprises constitutional law, administrative law, tax law and criminal law, as well as all procedural law. Laws concerning relationships between individuals belong to private law.

Usucaption, also known as acquisitive prescription, is a concept found in civil law systems and has its origin in the Roman law of property.

Citizenship in ancient Rome was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in Ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, traditions, and cultural practices. There existed several different types of citizenship, determined by one's gender, class, and political affiliations, and the exact duties or expectations of a citizen varied throughout the history of the Roman Empire.

In Roman law, mancipatio was a solemn verbal contract by which the ownership of certain types of goods was transferred. Mancipatio was also the legal procedure for drawing up wills, emancipating children from their parents, and adoption.

The ius gentium or jus gentium is a concept of international law within the ancient Roman legal system and Western law traditions based on or influenced by it. The ius gentium is not a body of statute law nor a legal code, but rather customary law thought to be held in common by all gentes in "reasoned compliance with standards of international conduct".

Latin rights were a set of legal rights that were originally granted to the Latins under Roman law in their original territory and therefore in their colonies. Latinitas was commonly used by Roman jurists to denote this status. With the Roman expansion in Italy, many settlements and coloniae outside of Latium had Latin rights.

In Roman law, status describes a person's legal status. The individual could be a Roman citizen, unlike foreigners; or he could be free, unlike slaves; or he could have a certain position in a Roman family either as head of the family, or as a lower member.

Slavery in ancient Rome played an important role in society and the economy. Unskilled or low-skill slaves labored in the fields, mines, and mills with few opportunities for advancement and little chance of freedom. Skilled and educated slaves—including artisans, chefs, domestic staff and personal attendants, entertainers, business managers, accountants and bankers, educators at all levels, secretaries and librarians, civil servants, and physicians—occupied a more privileged tier of servitude and could hope to obtain freedom through one of several well-defined paths with protections under the law. The possibility of manumission and subsequent citizenship was a distinguishing feature of Rome's system of slavery, resulting in a significant and influential number of freedpersons in Roman society.

Ius Italicum was a law in the early Roman Empire that allowed the emperors to grant cities outside Italy the legal fiction that they were on Italian soil. This meant that the city would be governed under Roman law rather than local law, and it would have a greater degree of autonomy in their relations with provincial governors. As Rome citizens, people were able to buy and sell property, were exempt from land tax, and the poll tax and were entitled to protection under Roman law. Ius Italicum was the highest liberty a municipality or province could obtain and was considered very favorable. Emperors, such as Augustus and Septimius Severus, made use of the law during their reign.

In the early Roman Empire, from 30 BC to AD 212, a peregrinus was a free provincial subject of the Empire who was not a Roman citizen. Peregrini constituted the vast majority of the Empire's inhabitants in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. In AD 212, all free inhabitants of the Empire were granted citizenship by the Constitutio Antoniniana, with the exception of the dediticii, people who had become subject to Rome through surrender in war, and freed slaves.

Ius or Jus in ancient Rome was a right to which a citizen (civis) was entitled by virtue of his citizenship (civitas). The iura were specified by laws, so ius sometimes meant law. As one went to the law courts to sue for one's rights, ius also meant justice and the place where justice was sought.

Usucapio was a concept in Roman law that dealt with the acquisition of ownership of something through possession. It was subsequently developed as a principle of civil law systems, usucaption. It is similar to the common law concept of adverse possession, or acquiring land prescriptively.

In ancient Rome, the dediticii or peregrini dediticii were a class of free provincials who were neither slaves nor citizens holding either full Roman citizenship as cives or Latin rights as Latini.

Res extra commercium is a doctrine originating in Roman law, holding that certain things may not be the object of private rights, and are therefore insusceptible to being traded.

A civitas foederata, meaning "allied state/community", was the most elevated type of autonomous cities and local communities under Roman rule.

The Lex Pompeia de Transpadanis was a Roman law promulgated by the Roman Consul Pompeius Strabo in 89 BC. It was one of three laws introduced by the Romans during the Social War between Rome and her Socii (allies), where some of Rome's Italic allies rebelled and waged war against her because of her refusal to grant them Roman citizenship. This law dealt with the local communities in Transpadana, the region north of the River Po,. It granted Latin Rights to these peoples as a reward for siding with the Rome during the Social War. This gave the inhabitants of the region the legal benefits associated with these rights, which were previously restricted to the towns of Latium which had not been incorporated into the Roman Republic and to the citizens of Latin colonies. They included: A) Ius Commercii, "a privilege granted to Latin colonies to have contractual relations, to trade with Roman citizens on equal terms and to use the form of contracts available to Roman citizens". It also allowed contracts and trade on equal terms with citizens of another Latin towns. B) Ius Connubii, was the right to conclude a marriage recognised by law, ius connubii of both parties was necessary for the validity of the marriage. Later it was extended to citizens of foreign communities "either generally, or by special concession". In the case of Latin rights it made marriages between citizens of different Latin towns legal. C) Ius migrationis, the right to retain one’s level of citizenship if the individual relocated to another city. In other words, it facilitated migration by the acquisition of citizenship of another Latin town. In addition to this, the law granted Roman citizenship to the magistrates (officials) of the local towns.

In Roman law, the praedial servitude or property easement, or simply servitude (servitutes), consists of a real right the owners of neighboring lands can establish voluntarily, in order that a property called servient lends to other called dominant the permanent advantage of a limited use. As use relations, servitudes are fundamentally solidary and indivisible rights, the latter being what causes the servitude to remain intact despite the fact that any property involved may be divided. Furthermore, there is no possibility of acquisition or partial extinction.

References

- ↑ Adolf Berger, entries on commercium and ius commercii, Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law (American Philological Society, 1953, 1991), p. 399, citing Ulpian, Epit. 19.5, and p. 527.

- ↑ Boudewijn Sirks, "Law, Commerce, and Finance in the Roman Empire," in Trade, Commerce, and the State in the Roman World (Oxford University Press, 2018), pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Saskia T. Roselaar, "The Concept of Commercium in the Roman Republic," Phoenix 66:3/4 (2012), pp. 381-413, noting (p. 382) that "farmland" may have been defined more narrowly as land designated as ager Romanus .