The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States that played a pivotal role for African Americans in the Civil Rights Movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission is "to bring about equality for all people regardless of race, creed, sex, age, disability, sexual orientation, religion or ethnic background."

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization. SCLC, which is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., had a large role in the American civil rights movement.

A sit-in or sit-down is a form of direct action that involves one or more people occupying an area for a protest, often to promote political, social, or economic change.

Racial equality occurs when institutions give equal opportunity to people of all races. In other words, institutions ignore persons' racial physical traits or skin color, and give everyone legally, morally, and politically equal opportunity. In Western society today, there is more diversity and more integration among races. Initially, attaining equality has been difficult for African, Asian, and Latino people, especially in schools. However, in the United States, racial equality, has become a law that regardless of what race an individual is, they will receive equal treatment, opportunity, education, employment, and politics.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. is a leading United States civil rights organization and law firm based in New York City.

The Greensboro sit-ins were a series of nonviolent protests in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1960, which led to the Woolworth department store chain removing its policy of racial segregation in the Southern United States. While not the first sit-in of the Civil Rights Movement, the Greensboro sit-ins were an instrumental action, and also the most well-known sit-ins of the Civil Rights Movement. They are considered a catalyst to the subsequent sit-in movement. These sit-ins led to increased national sentiment at a crucial period in US history. The primary event took place at the Greensboro, North Carolina, Woolworth store, now the International Civil Rights Center and Museum.

The Birmingham campaign, or Birmingham movement, was a movement organized in early 1963 by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to bring attention to the integration efforts of African Americans in Birmingham, Alabama. Led by Martin Luther King Jr., James Bevel, Fred Shuttlesworth and others, the campaign of nonviolent direct action culminated in widely publicized confrontations between young black students and white civic authorities, and eventually led the municipal government to change the city's discrimination laws.

The Albany Movement was a desegregation and voter's rights coalition formed in Albany, Georgia, in November of 1961. Local black leaders and ministers, as well as members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) founded the group. In December 1961, at the request of some senior leaders of The Albany Movement, Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) became involved in assisting the Albany group with organizing protests and demonstrations meant to draw attention to the continued and often brutally enforced racial segregation practices in Southwest Georgia. However, many leaders in SNCC were fundamentally opposed to King and the SCLC's involvement, as they felt a more democratic grassroots approach aimed at long-term solutions was preferable for the area than King's tendency towards short-term, authoritatively run organizing.

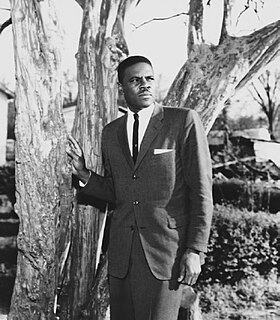

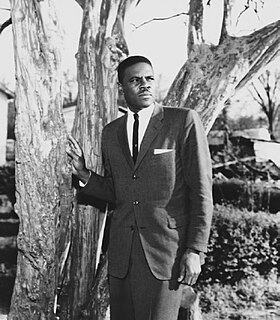

Floyd Bixler McKissick was an American lawyer and civil rights activist. He became the first African-American student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill's Law School. In 1966 he became leader of CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality, taking over from James L. Farmer, Jr. A supporter of Black Power, he turned CORE into a more radical movement. In 1968, McKissick left CORE to found Soul City in Warren County, North Carolina. He endorsed Richard Nixon for president that year, and the federal government, under President Nixon, supported Soul City. He became a state district court judge in 1990 and died on April 28, 1991. He was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.

Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company, 64 MCC 769 (1955) is a landmark civil rights case in the United States in which the Interstate Commerce Commission, in response to a bus segregation complaint filed in 1953 by a Women's Army Corps (WAC) private named Sarah Louise Keys, broke with its historic adherence to the Plessy v. Ferguson separate but equal doctrine and interpreted the non-discrimination language of the Interstate Commerce Act as banning the segregation of black passengers in buses traveling across state lines.

Douglas E. Moore is a Methodist minister who organized the 1957 Royal Ice Cream Sit-in in Durham, North Carolina. Moore entered the ministry at a young age. After finding himself dissatisfied with what he perceived as a lack of action among his divinity peers, he decided to take a more activist course. Shortly after becoming a pastor in Durham, Moore decided to challenge the city's power structure via the Royal Ice Cream Sit-in, a protest in which he and several others sat down in the white section of an ice cream parlor and asked to be served. The sit-in failed to challenge segregation in the short run, and Moore's actions provoked a myriad of negative reactions from many white and African-American leaders, who considered his efforts far too radical. Nevertheless, Moore continued to press forward with his agenda of activism.

William Gilmore "Bill" Enloe was an American businessman and politician who served as the Mayor of Raleigh, North Carolina from 1957 to 1963. Enloe was born in South Carolina and sold popcorn before moving to North Carolina and taking up work with North Carolina Theatres, Inc. In 1953 he was elected to the City Council of Raleigh. Four years later he was elected Mayor. During his tenure the American South was permeated by civil unrest due to racial segregation. Considered a moderate on civil rights, Enloe criticized black demonstrators and resisted efforts to integrate the theaters he managed, but he eventually compromised and appointed a committee to oversee the desegregation of Raleigh businesses. He left office in 1963, but returned to the city council in 1971. He died the following year. William G. Enloe High School in Raleigh was named in his honor.

Samuel Wilbert Tucker was an American lawyer and a cooperating attorney with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). His civil rights career began as he organized a 1939 sit-in at the then-segregated Alexandria, Virginia public library. A partner in the Richmond, Virginia, firm of Hill, Tucker and Marsh, Tucker argued and won several civil rights cases before the Supreme Court of the United States, including Green v. County School Board of New Kent County which, according to The Encyclopedia of Civil Rights In America, "did more to advance school integration than any other Supreme Court decision since Brown."

Golden Asro Frinks was an American civil rights activist and a Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) field secretary who represented the New Bern, North Carolina SCLC chapter. He is best known as a principal civil rights organizer in North Carolina during the 1960s which landed him a reputation as "The Great Agitator", having been jailed eighty-seven times during his lifetime.

Hocutt v. Wilson, N.C. Super. Ct. (1933) (unreported), was the first attempt to desegregate higher education in the United States. It was initiated by two African American lawyers from Durham, North Carolina, Conrad O. Pearson and Cecil McCoy, with the support of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The case was ultimately dismissed for lack of standing, but it served as a test case for challenging the "separate but equal" doctrine in education and was a precursor to Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

The Royal Ice Cream sit-in was a nonviolent protest in Durham, North Carolina, that led to a court case on the legality of segregated facilities. The demonstration took place on June 23, 1957 when a group of African American protesters, led by Reverend Douglas E. Moore, entered the Royal Ice Cream Parlor and sat in the section reserved for white patrons. When asked to move, the protesters refused and were arrested for trespassing. The case was appealed unsuccessfully to the County and State Superior Courts.

The New Orleans school desegregation crisis was a 1960 crisis over desegregation in schools located in New Orleans. Desegregation was a policy that introduced black students into all-white schools, as ordered by the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in 1954, in which the Court ruled racial segregation of public schools to be unconstitutional. There had been significant backlash from white New Orleans residents towards desegregating, and the New Orleans school board tried everything they could to postpone the mandatory desegregation from the federal government.

This is a timeline of the American civil rights movement, a nonviolent freedom movement to gain legal equality and the enforcement of constitutional rights for African Americans. The goals of the movement included securing equal protection under the law, ending legally established racial discrimination, and gaining equal access to public facilities, education reform, fair housing, and the ability to vote.

George Raymond was president of the Chester, Pennsylvania branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from 1942 to 1977. He was integral in the desegregation of businesses, public housing and schools in Chester and led civil rights demonstrations in 1964 which earned Chester the nickname "the Birmingham of the North".

Stanley Branche (1933-1992) was a civil rights leader from Pennsylvania who worked as executive secretary in the Chester, Pennsylvania branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and founded the Committee for Freedom Now (CFFN). In the early 1960s, he and George Raymond partnered to challenge minority hiring practices of businesses and initiated large civil rights protests against de facto segregation of schools which led to Chester being labeled the "Birmingham of the North". He worked with Cecil B. Moore to desegregate Girard College in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He left the civil rights movement in 1965 and ran multiple businesses. He ran unsuccessfully for mayor of Chester in 1967 and twice for U.S. Congress in 1978 and 1986. In 1989, he was convicted of participating in an organized crime collection scheme.