Firearms regulation in Switzerland allows the acquisition of semi-automatic, and – with a may-issue permit – fully automatic firearms, by Swiss citizens and foreigners with or without permanent residence. The laws pertaining to the acquisition of firearms in Switzerland are amongst the most liberal in the world. Swiss gun laws are primarily about the acquisition of arms, and not ownership. As such a license is not required to own a gun by itself, but a shall-issue permit is required to purchase most types of firearms. Bolt-action rifles, break-actions and hunting rifles do not require an acquisition permit, and can be acquired with just a background check. An explicit reason must be submitted to be issued an acquisition permit for handguns or semi-automatics unless the reason is sport-shooting, hunting or collecting. Permits for concealed carrying in public are issued sparingly. The acquisition of fully automatic weapons, suppressors and target lasers requires special permits issued by the cantonal firearms office. Police use of hollow point ammunition is limited to special situations.

The Dangerous Substances Directive was one of the main European Union laws concerning chemical safety, until its full replacement by the new regulation CLP Regulation (2008), starting in 2016. It was made under Article 100 of the Treaty of Rome. By agreement, it is also applicable in the EEA, and compliance with the directive will ensure compliance with the relevant Swiss laws. The Directive ceased to be in force on 31 May 2015 and was repealed by Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on classification, labelling and packaging of substances and mixtures, amending and repealing Directives 67/548/EEC and 1999/45/EC, and amending Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006.

The European Union Computer Programs Directive controls the legal protection of computer programs under the copyright law of the European Union. It was issued under the internal market provisions of the Treaty of Rome. The most recent version is Directive 2009/24/EC.

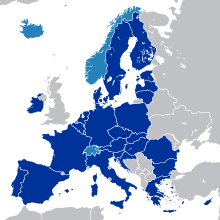

The visa policy of the Schengen Area is a component within the wider area of freedom, security and justice policy of the European Union. It applies to the Schengen Area and to other EU member states except Ireland. The visa policy allows nationals of certain countries to enter the Schengen Area via air, land or sea without a visa for up to 90 days within any 180-day period. Nationals of certain other countries are required to have a visa to enter and, in some cases, transit through the Schengen area.

As of 2009, the European Union had issued two units of measurement directives. In 1971, it issued Directive 71/354/EEC, which required EU member states to standardise on the International System of Units (SI) rather than use a variety of CGS and MKS units then in use. The second, which replaced the first, was Directive 80/181/EEC, enacted in 1979 and later amended several times, which issued a number of derogations to the United Kingdom and Ireland based on the former directive.

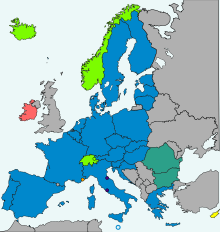

The European driving licence is a driving licence issued by the member states of the European Economic Area (EEA); all 27 EU member states and three EFTA member states; Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway, which give shared features the various driving licence styles formerly in use. It is credit card-style with a photograph. They were introduced to replace the 110 different plastic and paper driving licences of the 300 million drivers in the EEA. The main objective of the licence is to reduce the risk of fraud.

Asulam is a herbicide invented by May & Baker Ltd, internally called M&B9057, that is used in horticulture and agriculture to kill bracken and docks. It is also used as an antiviral agent. It is currently marketed, by United Phosphorus Ltd - UPL, as "Asulox" which contains 400 g/L of asulam sodium salt.

The CLP Regulation is a European Union regulation from 2008, which aligns the European Union system of classification, labelling and packaging of chemical substances and mixtures to the Globally Harmonised System (GHS). It is expected to facilitate global trade and the harmonised communication of hazard information of chemicals and to promote regulatory efficiency. It complements the 2006 Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) Regulation and replaces an older system contained in the Dangerous Substances Directive (67/548/EEC) and the Dangerous Preparations Directive (1999/45/EC).

Council Directive 76/768/EEC of 27 July 1976 on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to cosmetic products was the main European Union law on the safety of cosmetics. It was made under Art. 100 of the Treaty of Rome. By agreement, it was also applicable in the European Economic Area.

Directive 89/391/EEC is a European Union directive with the objective to introducing measures to encourage improvements in the safety and health of workers at work. It is described as a "Framework Directive" for occupational safety and health (OSH) by the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work.

The Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive 1991 European Union directive concerning urban waste water "collection, treatment and discharge of urban waste water and the treatment and discharge of waste water from certain industrial sectors". It aims "to protect the environment from adverse effects of waste water discharges from cities and "certain industrial sectors". Council Directive 91/271/EEC on Urban Wastewater Treatment was adopted on 21 May 1991, amended by the Commission Directive 98/15/EC.

The Single European Railway Directive 2012 is an EU Directive that regulates railway networks in European Union law. This recast the First Railway Directive" and consolidates legislation from each of the first to the fourth "Package" from 1991 to 2016, and allows open access operations on railway lines by companies other than those that own the rail infrastructure. The legislation was extended by further directives to include cross border transit of freight.

The European Firearms Pass (EFP) is a locally issued firearms licence in a common format that allows citizens of the European Union (EU) to travel with one or more firearm(s) mentioned on the licence from one member state to another. For certain purposes other documentation may be required, depending on the current states' laws and the reason for the movement; a transfer may be temporary or permanent. An applicant for an EFP must already hold a licence from the member state in which he/she holds the firearm.

The Transparency Directive, Transparency Obligations Directive or Directive 2004/109/EC is an EU Directive issued in 2004, revising an earlier Directive 2001/34/EC. The Transparency Directive was amended in 2013 by the Transparency Directive Amending Directive.

The Machinery Directive, Directive 2006/42/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 May 2006 is a European Union directive concerning machinery and certain parts of machinery. Its main intent is to ensure a common safety level in machinery placed on the market or put in service in all member states and to ensure freedom of movement within the European Union by stating that "member states shall not prohibit, restrict or impede the placing on the market and/or putting into service in their territory of machinery which complies with [the] Directive".

European company law is the part of European Union law which concerns the formation, operation and insolvency of companies in the European Union. The EU creates minimum standards for companies throughout the EU, and has its own corporate forms. All member states continue to operate separate companies acts, which are amended from time to time to comply with EU Directives and Regulations. There is, however, also the option of businesses to incorporate as a Societas Europaea (SE), which allows a company to operate across all member states.

A pesticide, also called Plant Protection Product (PPP), which is a term used in regulatory documents, consists of several different components. The active ingredient in a pesticide is called “active substance” and these active substances either consist of chemicals or micro-organisms. The aims of these active substances are to specifically take action against organisms that are harmful to plants. In other words, active substances are the active components against pests and plant diseases.

The Energy Taxation Directive or ETD (2003/96/EC) is a European directive, which establishes the framework conditions of the European Union for the taxation of electricity, motor and aviation fuels and most heating fuels. The directive is part of European Union energy law; its core component is the setting of minimum tax rates for all Member States.

The history of Czech civilian firearms possession extends over 600 years back when the Czech lands became the center of firearms development, both as regards their technical aspects as well as tactical use.