Events

Assassination of Cáceres

On 19 November 1911, General Luis Tejera led a group of conspirators in an ambush on the horse-drawn carriage of President Ramón Cáceres. During the shootout, Cáceres was killed and Tejera wounded in the leg. The assassins fled in an automobile, which they soon crashed into a river. After rescuing Tejera from the water and depositing him in a hut by the road the other conspirators fled on foot. Tejera was found shortly after and summarily executed.

Civil war

In the ensuing power vacuum, General Alfredo Victoria, commander of the Dominican Army, seized control and forced the Congress to elect his uncle, Eladio Victoria, as the new interim president on 5 December 1911. The general was widely suspected of bribing the Congress, and his uncle, who took office officially as president on 27 February 1912, lacked legitimacy. The former president Horacio Vásquez soon returned from exile to lead his followers, the horacistas , in a popular uprising against the new government. He joined forces with the border caudillo General Desiderio Arias and by December the country was in a state of civil war. The violence prompted the United States to abandon the customs houses it operated on the Haitian border, despite the fact that they had not been targeted. The small American force that monitored the frontier to combat smuggling also withdrew, handing over responsibility for border defence to the Dominican Army. Men and weapons passed freely over the Haitian border to the rebels as the Haitian government tried to promote instability in its neighbour. On 12 April 1912, the American consul general, Thomas Cleland Dawson, reported that "the government has a well-equipped force in the field and could soon put down the rebellion on the northwestern frontier were it not for the effective aid they claim the Haitian government is giving it." General Arias's forces seized the customs houses and extorted loans from the peasants and plantation owners in the districts they controlled. The officers of the corrupt Dominican Army commonly pocketed their troops' pay and plundered the territories they were sent to subdue.

The chaotic situation was to the advantage of the military leadership of both sides, who enriched themselves at the people's expense. A report emanating from the American legation, dated 3 August, blamed the military for prolonging the conflict. [4] Towards the end of September, the President of the United States, William Howard Taft, sent a commission to investigate options for obtaining peace. Taft did not seek the permission of the Dominican government, but did give them advance notice prior to the commission's arrival on 2 October. That same day the Dominican government decided to make 12 October an official holiday, the Día de Colón (Columbus Day), in an effort to please the Americans. An executive decree was published to this effect on 5 October. On 20 November the Dominican foreign minister suggested that other countries should adopt the holiday, so that "all the American nations would have a common holiday". The day is now celebrated as the Día de la Raza .

The American commission reported on 13 November that the military's self-interest and the rebels' confidence precluded any mutual agreement to end the fighting. [5] The Taft administration then reduced its payouts to the Dominican government down to 45% of customs revenues, which was the floor established when Dominican customs came under American receivership through the convention of 1907. The United States further threatened to transfer formal recognition to the rebels and cede all the 45% of customs revenues to them unless President Victoria resigned. The presence of the U.S. Navy and 750 U.S. Marines gave force to the threat. Victoria announced his resignation on 26 November and stepped down as president on 30 November. American official met with the rebel leader, Vásquez, and Archbishop of Santo Domingo Adolfo Alejandro Nouel was appointed interim president on 30 November. Nouel was tasked with holding free elections, but Arias soon defied the government. After four months Nouel resigned and Congress elected as his successor Senator José Bordas Valdez, who took office on 14 April 1913. Valdez's sole concern was to remain president.

The Dominican Republic is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with Haiti, making Hispaniola one of only two Caribbean islands, along with Saint Martin, that is shared by two sovereign states. It is the second-largest nation in the Antilles by area at 48,671 square kilometers (18,792 sq mi), and second-largest by population, with approximately 11.4 million people in 2024, of whom approximately 3.6 million live in the metropolitan area of Santo Domingo, the capital city.

The recorded history of the Dominican Republic began in 1492 when the Genoa-born navigator Christopher Columbus, working for the Crown of Castile, happened upon a large island in the region of the western Atlantic Ocean that later came to be known as the Caribbean. It was inhabited by the Taíno, an Arawakan people, who called the eastern part of the island Quisqueya (Kiskeya), meaning "mother of all lands." Columbus promptly claimed the island for the Spanish Crown, naming it La Isla Española, later Latinized to Hispaniola. After 25 years of Spanish occupation, the Taíno population in the Spanish-dominated parts of the island drastically decreased through genocide. With fewer than 50,000 remaining, the survivors intermixed with Spaniards, Africans, and others, forming the present-day tripartite Dominican population. What would become the Dominican Republic was the Spanish Captaincy General of Santo Domingo until 1821, except for a time as a French colony from 1795 to 1809. It was then part of a unified Hispaniola with Haiti from 1822 until 1844. In 1844, Dominican independence was proclaimed and the republic, which was often known as Santo Domingo until the early 20th century, maintained its independence except for a short Spanish occupation from 1861 to 1865 and occupation by the United States from 1916 to 1924.

Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina, nicknamed El Jefe ), was a Dominican military commander and dictator who ruled the Dominican Republic from August 1930 until his assassination in May 1961. He served as president from 1930 to 1938 and again from 1942 to 1952, ruling for the rest of his life as an unelected military strongman under figurehead presidents. His rule of 31 years, known to Dominicans as the Trujillo Era, was one of the longest for a non-royal leader in the world, and centered around a personality cult of the ruling family. It was also one of the most brutal; Trujillo's security forces, including the infamous SIM, were responsible for perhaps as many as 50,000 murders. These included between 12,000 and 30,000 Haitians in the infamous Parsley massacre in 1937, which continues to affect Dominican-Haitian relations to this day.

The United States occupation of Haiti began on July 28, 1915, when 330 U.S. Marines landed at Port-au-Prince, Haiti, after the National City Bank of New York convinced the President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, to take control of Haiti's political and financial interests. The July 1915 invasion took place following years of socioeconomic instability within Haiti that culminated with the lynching of President of Haiti Vilbrun Guillaume Sam by a mob angered by his decision to order the executions of political prisoners. The invasion and subsequent occupation was promoted by growing American business interests in Haiti, especially the National City Bank of New York, which had withheld funds from Haiti and paid rebels to destabilize the nation through the Bank of the Republic of Haiti with an aim at inducing American intervention.

The Dominican War of Independence was a war of independence that began when the Dominican Republic declared independence from the Republic of Haiti on February 27, 1844 and ended on January 24, 1856. Before the war, the island of Hispaniola had been united for 22 years when the newly independent nation, previously known as the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo, was unified with the Republic of Haiti in 1822. The criollo class within the country overthrew the Spanish crown in 1821 before unifying with Haiti a year later.

The Republic of Spanish Haiti, also called the Independent State of Spanish Haiti was the independent state that succeeded the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo after independence was declared on November 30, 1821 by José Núñez de Cáceres. The republic lasted only from December 1, 1821 to February 9, 1822 when it was invaded by the Republic of Haiti.

The first United States occupation of the Dominican Republic lasted from 1916 to 1924. It aimed to force the Dominicans to repay their large debts to European creditors, whose governments threatened military intervention. On May 13, 1916, Rear Admiral William B. Caperton forced the Dominican Republic's Secretary of War Desiderio Arias, who had seized power from President Juan Isidro Jimenes Pereyra, to leave Santo Domingo by threatening the city with naval bombardment. The Marines landed three days later and established effective control of the country within two months. Three major roads were built, largely for military purposes, connecting for the first time the capital with Santiago in the Cibao, Azua in the west, and San Pedro de Macorís in the east; and the system of forced labor used by the Americans in Haiti was absent in the Dominican Republic.

The Banana Wars were a series of conflicts that consisted of military occupation, police action, and intervention by the United States in Central America and the Caribbean between the end of the Spanish–American War in 1898 and the inception of the Good Neighbor Policy in 1934. The military interventions were primarily carried out by the United States Marine Corps, which also developed a manual, the Small Wars Manual (1921) based on their experiences. On occasion, the United States Navy provided gunfire support and the United States Army also deployed troops.

The Haitian occupation of Santo Domingo was the annexation and merger of then-independent Republic of Spanish Haiti into the Republic of Haiti, that lasted twenty-two years, from February 9, 1822, to February 27, 1844. The part of Hispaniola under Spanish administration was first ceded to France and merged with the French colony of Saint Domingue as a result of the Peace of Basel in 1795. However, with the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution the French lost the western part of the island, while remaining in control of the eastern part of the island until the Spanish recaptured Santo Domingo in 1809.

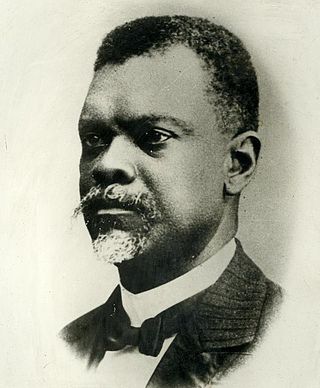

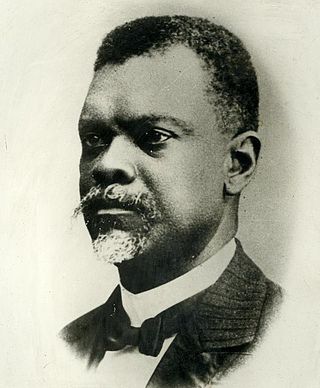

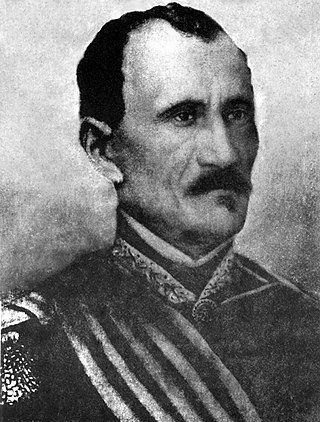

Ramón Arturo Cáceres Vasquez, nicknamed Mon Cáceres, was a Dominican Republic politician and minister of the Armed Forces. He was the 31st president of the Dominican Republic (1906–1911). He served as vice president under Carlos Felipe Morales until assuming office in 1906. Cáceres was the leader of the right-wing Red Party.

Emmanuel Oreste Zamor was a Haitian general and politician who served as the president of Haiti in 1914. He was executed the following year after being ousted in a coup.

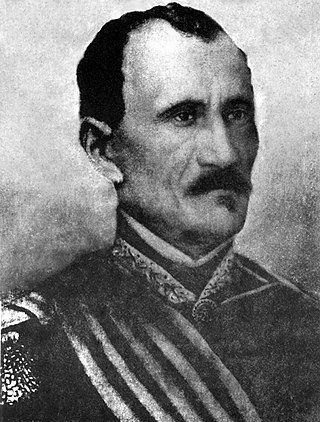

General José María Cabral y Luna was a Dominican military figure and politician. He served as the first Supreme Chief of the Dominican Republic from August 4, 1865, to November 15 of that year and again officially as president from August 22, 1866, until January 3, 1868.

La Trinitaria was a secret society founded in 1838 in what today is known as Arzobispo Nouel Street, across from the "Del Carmen's Church" in the then occupied Santo Domingo, the current capital of the Dominican Republic. The founder, Juan Pablo Duarte, and a group of like minded young people, led the struggle to establish the Dominican Republic as a free, sovereign, and independent nation in the 19th century. Their main goal was to protect their newly liberated country from all foreign invasion. They helped bring about the end of the Haitian occupation of Santo Domingo from 1822 to 1844.

José Núñez de Cáceres y Albor was a Dominican revolutionary and writer. He is known for being the leader of the first Dominican independence movement against Spain in 1821. His revolutionary activities preceded the Dominican War of Independence.

José Bordas Valdez was a politician from the Dominican Republic. He served as the 2nd provisional president of the Dominican Republic from April 14, 1913, until August 27, 1914. He was born in Santiago de los Caballeros. During his government he had to face the "Railroad Revolution".

Dominican Republic–Haiti relations are the diplomatic relations between the nations of Dominican Republic and Haiti. Relations have long been hostile due to substantial ethnic and cultural differences, historic conflicts, territorial disputes, and sharing the island of Hispaniola, part of the Greater Antilles archipelago in the Caribbean region. The living standards in the Dominican Republic are considerably higher than those in Haiti. The economy of the Dominican Republic is ten times larger than that of Haiti. The migration of impoverished Haitians and historical differences have contributed to long-standing conflicts.

The Dominican Civil War (1914) was a civil war in the Dominican Republic that started as a rebellion against the government led by General Desiderio Arias in La Vega and Santiago de los Caballeros, beginning on March 30, 1914. José Bordas Valdez was elected President without opposition on June 15, 1914. The U.S. Navy ships intervened to end the bombardment of Puerto Plata beginning on June 26, 1914. The U.S. Army troops were deployed in support of the government in Santo Domingo in July 1914. The U.S. government mediated the signing of a ceasefire agreement between government and rebel representatives on August 6, 1914. Some 500 individuals were killed during the conflict.

The Second Dominican Republic was a predecessor of the Dominican Republic and began with the restoration of the country in 1865 and culminated with the American intervention in 1916.

Dominican Republic–Spain relations are the bilateral relations between the Dominican Republic and Spain. Both nations are members of the Association of Academies of the Spanish Language and the Organization of Ibero-American States.

The Republic of Haiti from 1820 to 1849 was effectively a continuation of the first Republic of Haiti that had been in control of the south of what is now Haiti since 1806. This period of Haitian history commenced with the fall of the Kingdom of Haiti in the north and the reunification of Haiti in 1820 under Jean-Pierre Boyer. This period also encompassed Haitian occupation of Spanish Santo Domingo from 1822 to 1844, creating a unified political entity governing the entire island of Hispaniola. Although termed a republic, this period was dominated by Boyer's authoritarian rule as president-for-life until 1843. The first Republic of Haiti ended in 1849 when President Faustin Soulouque declared himself emperor, thus beginning the Second Empire of Haiti.