Egyptomania may refer to:

- Ancient Egypt in the Western imagination, interest of ancient Egypt in Europe from the Victorian Age on

- Egyptomania in the United States, interest in ancient Egypt specific to the United States

Egyptomania may refer to:

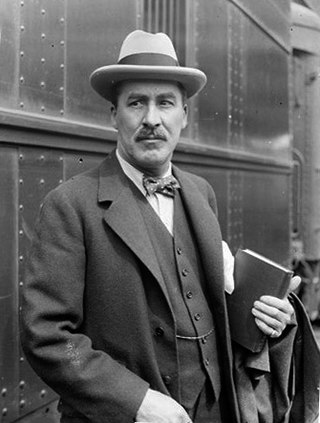

Howard Carter was a British archaeologist and Egyptologist who discovered the intact tomb of the 18th Dynasty Pharaoh Tutankhamun in November 1922, the best-preserved pharaonic tomb ever found in the Valley of the Kings.

Thebes or Thebae may refer to one of the following places:

HU or Hu may refer to:

Music has been an integral part of Egyptian culture since antiquity in Egypt. Egyptian music had a significant impact on the development of ancient Greek music, and via the Greeks it was important to early European music well into the Middle Ages. Due to the thousands of-years long dominance of Egypt over its neighbors, Egyptian culture, including music and musical instruments, was very influential in the surrounding regions; for instance, the instruments claimed in the Bible to have been played by the ancient Hebrews are all Egyptian instruments as established by Egyptian archaeology. Egyptian modern music is considered as a main core of Middle Eastern and Oriental music as it has a huge influence on the region due to the popularity and huge influence of Egyptian cinema and music industries, owing to the political influence Egypt has on its neighboring countries, as well as Egypt producing the most accomplished musicians and composers in the region, specially in the 20th century, a lot of them are of international stature. The tonal structure music in the East is defined by the maqamat, loosely similar to the Western modes, while the rhythm in the East is governed by the iqa'at, standard rhythmic modes formed by combinations of accented and unaccented beats and rests.

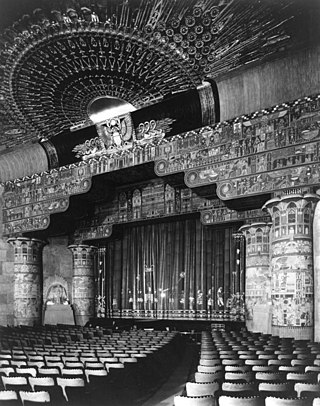

Egyptian Revival is an architectural style that uses the motifs and imagery of ancient Egypt. It is attributed generally to the public awareness of ancient Egyptian monuments generated by Napoleon's conquest of Egypt and Admiral Nelson's defeat of the French Navy at the Battle of the Nile in 1798. Napoleon took a scientific expedition with him to Egypt. Publication of the expedition's work, the Description de l'Égypte, began in 1809 and was published as a series through 1826. The size and monumentality of the façades discovered during his adventure cemented the hold of Egyptian aesthetics on the Parisian elite. However, works of art and architecture in the Egyptian style had been made or built occasionally on the European continent since the time of the Renaissance.

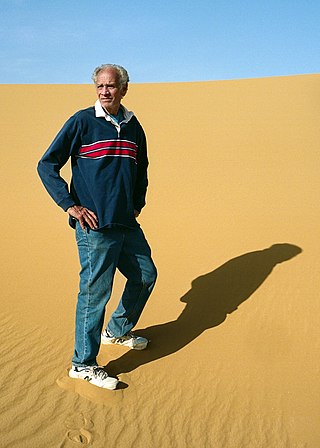

Robert Brier is an American Egyptologist specializing in paleopathology. A senior research fellow at Long Island University/LIU Post, he has researched and published on mummies and the mummification process and has appeared in many Discovery Civilization, TLC Network, and National Geographic documentaries, primarily on ancient Egypt. He is recognized as one of the world's foremost Egyptologists.

Medjay was a demonym used in various ways throughout ancient Egyptian history to refer initially to a nomadic group from Nubia and later as a generic term for desert-ranger police.

Egypt has had a legendary image in the Western world through the Greek and Hebrew traditions. Egypt was already ancient to outsiders, and the idea of Egypt has continued to be at least as influential in the history of ideas as the actual historical Egypt itself. All Egyptian culture was transmitted to Roman and post-Roman European culture through the lens of Hellenistic conceptions of it, until the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphics by Jean-François Champollion in the 1820s rendered Egyptian texts legible, finally enabling an understanding of Egypt as the Egyptians themselves understood it.

George Robbins Gliddon was an English-born American Egyptologist. He worked as a United States vice-consul in Egypt and assisted Muhammad Ali Pasha's plans to modernize Egypt by attaining sugar, rice, and other mills from the United States. In 1841, he became frustrated with Pasha's destruction of archaeological sites and wrote Appeal to the Antiquaries of Europe on the Destruction of the Monuments of Egypt.

Egyptomania refers to a period of renewed interest in the culture of ancient Egypt sparked by Napoleon's Egyptian Campaign in the 19th century. Napoleon was accompanied by many scientists and scholars during this campaign, which led to a large interest in the documentation of ancient monuments in Egypt. Thorough documentation of ancient ruins led to an increase in the interest about ancient Egypt. In 1822, Jean-François Champollion deciphered the ancient hieroglyphs by using the Rosetta Stone that was recovered by French troops in 1799, and hence began the scientific study of egyptology.

Merit may refer to:

Egyptian-style theatres are based on the traditional and historic design elements of Ancient Egypt.

"Lot No. 249" is a Gothic horror short story by British writer Arthur Conan Doyle, first published in Harper's Magazine in 1892. The story tells of a University of Oxford athlete named Abercrombie Smith who notices a strange series of events surrounding Edward Bellingham, an Egyptology student who owns many ancient Egyptian artefacts, including a mummy. After seeing his mummy disappear and reappear, and two instances of Bellingham's enemies being attacked, Smith concludes that Bellingham is re-animating his mummy.

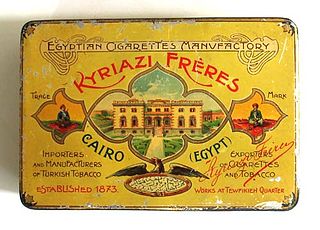

The Egyptian cigarette industry, during the period between the 1880s and the end of the First World War, was a major export industry that influenced global fashion. It was notable as a rare example of the global periphery setting trends in the global center in a period when the predominant direction of cultural influence was the reverse, and also as one of the earliest producers of globally traded manufactured finished goods outside the West.

Egyptian revival decorative arts is a style in Western art, mainly of the early nineteenth century, in which Egyptian motifs were applied to a wide variety of decorative arts objects.

The Monster is a 1903 French silent trick film directed by Georges Méliès.

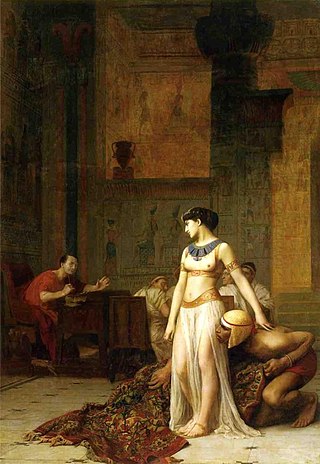

Cleopatra and Caesar, also known as Cleopatra Before Caesar, is an oil-on-canvas painting by the French Academic artist Jean-Léon Gérôme, completed in 1866. The work was originally commissioned by the French courtesan La Païva, but she was unhappy with the finished painting and returned it to Gérôme. It was exhibited at the Salon of 1866 and the Royal Academy of Arts in 1871.

Mummies: A Voyage Through Eternity is a 1991 illustrated monograph on the Egyptian mummies, ancient Egyptian funerary practices and the history of the discoveries of Egyptian mummies. Co-written by the French historian Françoise Dunand and the medical doctor Roger Lichtenberg, and published in pocket format by Éditions Gallimard as the 118th volume in the "Découvertes Gallimard" collection.

Hoteps are members of an Afrocentrist African American subculture that focuses on Ancient Egypt as a source of Black pride. The group has been described as promoting pseudohistory and misinformation about Black history. Hoteps espouse a mixture of Black radicalism and social conservatism.