Related Research Articles

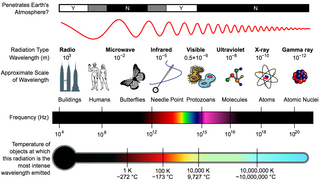

The electromagnetic spectrum is the full range of electromagnetic radiation, organized by frequency or wavelength. The spectrum is divided into separate bands, with different names for the electromagnetic waves within each band. From low to high frequency these are: radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visible light, ultraviolet, X-rays, and gamma rays. The electromagnetic waves in each of these bands have different characteristics, such as how they are produced, how they interact with matter, and their practical applications.

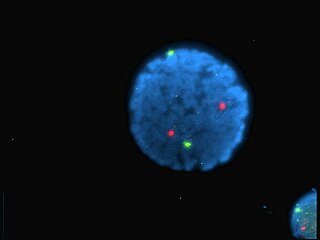

Fluorescence is the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. It is a form of luminescence. In most cases, the emitted light has a longer wavelength, and therefore a lower photon energy, than the absorbed radiation. A perceptible example of fluorescence occurs when the absorbed radiation is in the ultraviolet region of the electromagnetic spectrum, while the emitted light is in the visible region; this gives the fluorescent substance a distinct color that can only be seen when the substance has been exposed to UV light. Fluorescent materials cease to glow nearly immediately when the radiation source stops, unlike phosphorescent materials, which continue to emit light for some time after.

In organic chemistry, a peptide bond is an amide type of covalent chemical bond linking two consecutive alpha-amino acids from C1 of one alpha-amino acid and N2 of another, along a peptide or protein chain.

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or a material medium. This includes:

Optical rotation, also known as polarization rotation or circular birefringence, is the rotation of the orientation of the plane of polarization about the optical axis of linearly polarized light as it travels through certain materials. Circular birefringence and circular dichroism are the manifestations of optical activity. Optical activity occurs only in chiral materials, those lacking microscopic mirror symmetry. Unlike other sources of birefringence which alter a beam's state of polarization, optical activity can be observed in fluids. This can include gases or solutions of chiral molecules such as sugars, molecules with helical secondary structure such as some proteins, and also chiral liquid crystals. It can also be observed in chiral solids such as certain crystals with a rotation between adjacent crystal planes or metamaterials.

In physics, attenuation is the gradual loss of flux intensity through a medium. For instance, dark glasses attenuate sunlight, lead attenuates X-rays, and water and air attenuate both light and sound at variable attenuation rates.

Circular dichroism (CD) is dichroism involving circularly polarized light, i.e., the differential absorption of left- and right-handed light. Left-hand circular (LHC) and right-hand circular (RHC) polarized light represent two possible spin angular momentum states for a photon, and so circular dichroism is also referred to as dichroism for spin angular momentum. This phenomenon was discovered by Jean-Baptiste Biot, Augustin Fresnel, and Aimé Cotton in the first half of the 19th century. Circular dichroism and circular birefringence are manifestations of optical activity. It is exhibited in the absorption bands of optically active chiral molecules. CD spectroscopy has a wide range of applications in many different fields. Most notably, UV CD is used to investigate the secondary structure of proteins. UV/Vis CD is used to investigate charge-transfer transitions. Near-infrared CD is used to investigate geometric and electronic structure by probing metal d→d transitions. Vibrational circular dichroism, which uses light from the infrared energy region, is used for structural studies of small organic molecules, and most recently proteins and DNA.

Sunrise is the moment when the upper rim of the Sun appears on the horizon in the morning. The term can also refer to the entire process of the solar disk crossing the horizon.

In theoretical chemistry, a conjugated system is a system of connected p-orbitals with delocalized electrons in a molecule, which in general lowers the overall energy of the molecule and increases stability. It is conventionally represented as having alternating single and multiple bonds. Lone pairs, radicals or carbenium ions may be part of the system, which may be cyclic, acyclic, linear or mixed. The term "conjugated" was coined in 1899 by the German chemist Johannes Thiele.

Gel electrophoresis of nucleic acids is an analytical technique to separate DNA or RNA fragments by size and reactivity. Nucleic acid molecules are placed on a gel, where an electric field induces the nucleic acids to migrate toward the positively charged anode. The molecules separate as they travel through the gel based on the each molecule's size and shape. Longer molecules move more slowly because they the gel resists their movement more forcefully than it resists shorter molecules. After some time, the electricity is turned off and the positions of the different molecules are analyzed.

The color of chemicals is a physical property of chemicals that in most cases comes from the excitation of electrons due to an absorption of energy performed by the chemical. What is seen by the eye is not the color absorbed, but the complementary color from the removal of the absorbed wavelengths. This spectral perspective was first noted in atomic spectroscopy.

Fluorescence spectroscopy is a type of electromagnetic spectroscopy that analyzes fluorescence from a sample. It involves using a beam of light, usually ultraviolet light, that excites the electrons in molecules of certain compounds and causes them to emit light; typically, but not necessarily, visible light. A complementary technique is absorption spectroscopy. In the special case of single molecule fluorescence spectroscopy, intensity fluctuations from the emitted light are measured from either single fluorophores, or pairs of fluorophores.

A fluorophore is a fluorescent chemical compound that can re-emit light upon light excitation. Fluorophores typically contain several combined aromatic groups, or planar or cyclic molecules with several π bonds.

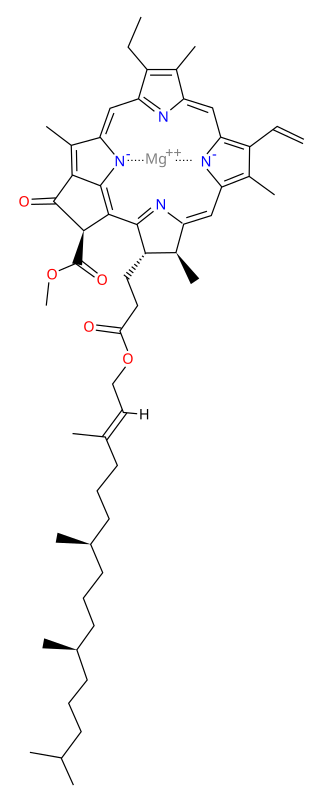

Chlorophyll a is a specific form of chlorophyll used in oxygenic photosynthesis. It absorbs most energy from wavelengths of violet-blue and orange-red light, and it is a poor absorber of green and near-green portions of the spectrum. Chlorophyll does not reflect light but chlorophyll-containing tissues appear green because green light is diffusively reflected by structures like cell walls. This photosynthetic pigment is essential for photosynthesis in eukaryotes, cyanobacteria and prochlorophytes because of its role as primary electron donor in the electron transport chain. Chlorophyll a also transfers resonance energy in the antenna complex, ending in the reaction center where specific chlorophylls P680 and P700 are located.

A chromophore is a molecule which absorbs light at a particular wavelength and emits color as a result. Chromophores are commonly referred to as colored molecules for this reason. The word is derived from Ancient Greek χρῶμᾰ (chroma) 'color', and -φόρος (phoros) 'carrier of'. Many molecules in nature are chromophores, including chlorophyll, the molecule responsible for the green colors of leaves. The color that is seen by our eyes is that of the light not absorbed by the reflecting object within a certain wavelength spectrum of visible light. The chromophore indicates a region in the molecule where the energy difference between two separate molecular orbitals falls within the range of the visible spectrum. Visible light that hits the chromophore can thus be absorbed by exciting an electron from its ground state into an excited state. In biological molecules that serve to capture or detect light energy, the chromophore is the moiety that causes a conformational change in the molecule when hit by light.

The color of water varies with the ambient conditions in which that water is present. While relatively small quantities of water appear to be colorless, pure water has a slight blue color that becomes deeper as the thickness of the observed sample increases. The hue of water is an intrinsic property and is caused by selective absorption and scattering of blue light. Dissolved elements or suspended impurities may give water a different color.

In organic chemistry, an auxochrome is a group of atoms attached to a chromophore which modifies the ability of that chromophore to absorb light. They themselves fail to produce the colour, but instead intensify the colour of the chromogen when present along with the chromophores in an organic compound. Examples include the hydroxyl, amino, aldehyde, and methyl mercaptan groups.

Nitrogen trioxide or nitrate radical is an oxide of nitrogen with formula NO

3, consisting of three oxygen atoms covalently bound to a nitrogen atom. This highly unstable blue compound has not been isolated in pure form, but can be generated and observed as a short-lived component of gas, liquid, or solid systems.

Water is a polar inorganic compound that is at room temperature a tasteless and odorless liquid, which is nearly colorless apart from an inherent hint of blue. It is by far the most studied chemical compound and is described as the "universal solvent" and the "solvent of life". It is the most abundant substance on the surface of Earth and the only common substance to exist as a solid, liquid, and gas on Earth's surface. It is also the third most abundant molecule in the universe.

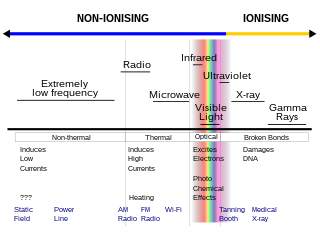

Non-ionizingradiation refers to any type of electromagnetic radiation that does not carry enough energy per quantum to ionize atoms or molecules—that is, to completely remove an electron from an atom or molecule. Instead of producing charged ions when passing through matter, non-ionizing electromagnetic radiation has sufficient energy only for excitation. Non-ionizing radiation is not a significant health risk. In contrast, ionizing radiation has a higher frequency and shorter wavelength than non-ionizing radiation, and can be a serious health hazard: exposure to it can cause burns, radiation sickness, many kinds of cancer, and genetic damage. Using ionizing radiation requires elaborate radiological protection measures, which in general are not required with non-ionizing radiation.