Related Research Articles

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1770.

John Witherspoon was a Scottish-American Presbyterian minister, educator, farmer, slaveholder, and a Founding Father of the United States. Witherspoon embraced the concepts of Scottish common sense realism, and while president of the College of New Jersey became an influential figure in the development of the United States' national character. Politically active, Witherspoon was a delegate from New Jersey to the Second Continental Congress and a signatory to the July 4, 1776, Declaration of Independence. He was the only active clergyman and the only college president to sign the Declaration. Later, he signed the Articles of Confederation and supported ratification of the Constitution of the United States.

William Paterson was an American statesman, lawyer, jurist, and signer of the United States Constitution. He was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, the second governor of New Jersey, and a Founding Father of the United States.

The American Whig–Cliosophic Society, sometimes abbreviated as Whig-Clio, is a political, literary, and debating society at Princeton University and the oldest debate union in the United States. Its precursors, the American Whig Society and the Cliosophic Society, were founded at Princeton in 1769 and 1765.

Philip Morin Freneau was an American poet, nationalist, polemicist, sea captain and early American newspaper editor sometimes called the "Poet of the American Revolution". Through his Philadelphia newspaper, the National Gazette, he was a strong critic of George Washington and a proponent of Jeffersonian policies.

Whig or Whigs may refer to:

Abraham Watkins Venable was a 19th-century US politician and lawyer from North Carolina. He was an enslaver. Venable was the nephew of congressman and senator Abraham B. Venable.

Annis Boudinot Stockton was an American poet, one of the first women to be published in the Thirteen Colonies. Living in Princeton, New Jersey, Stockton wrote and published her poems in leading newspapers and magazines of the day and was part of a Mid-Atlantic writing circle. She was the author of more than 120 works, but it was not until 1985, when a manuscript copybook long held privately was given to the New Jersey Historical Society, that most of them became known. Before that, she was known to have written 40 poems. The copybook contained poems that tripled the amount of her known work. A complete collection of her works was published in 1995. She is featured in the permanent exhibit at Morven Museum & Garden in Princeton, NJ.

Hugh Henry Brackenridge was an American writer, lawyer, judge, and justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania.

The Philoclean Society at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey is one of the oldest collegiate literary societies in the United States, and among the oldest student organizations at Rutgers University. Founded in 1825, the society was one of two such organizations—the other being the Peithessophian Society—on campus devoted to the same purpose.

John Trumbull was an American poet.

Charles McKnight was an American physician during and after the American Revolutionary War. He served as a surgeon and physician in the Hospital Department of the Continental Army under General George Washington and other subordinate commanders. McKnight was one of the most respected surgeons of his day and was remembered by one colleague as "particularly distinguished as a practical surgeon … at the time of his death (he) was without a rival in that branch of his profession."

Princeton University eating clubs are private institutions resembling both dining halls and social houses, where the majority of Princeton undergraduate upperclassmen eat their meals. Each eating club occupies a large mansion on Prospect Avenue, one of the main roads that runs through the Princeton campus, with the exception of Terrace Club which is just around the corner on Washington Road. This area is known to students colloquially as "The Street". Princeton's eating clubs are the primary setting in F. Scott Fitzgerald's 1920 debut novel, This Side of Paradise, and the clubs appeared prominently in the 2004 novel The Rule of Four.

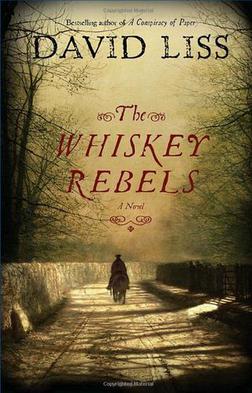

The Whiskey Rebels is a 2008 historical novel by American writer David Liss, inspired by events in the early history of the United States. According to Liss, "This novel, in many respects, details the events that led up to the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794".

College literary societies in American higher education are a particular kind of social organization, distinct from literary societies generally, and they were often the precursors of college fraternities and sororities. In the period from the late 18th century to the Civil War, collegiate literary societies were an important part of campus social life. These societies are often called Latin literary societies because they typically have compound Latinate names.

Joseph Cabell Breckinridge was an American lawyer, soldier, slaveholder and politician in Kentucky. From 1816 to 1819, he represented Fayette County in the Kentucky House of Representatives, and fellow members elected him as their speaker. In 1820, Governor John Adair appointed Breckinridge Kentucky Secretary of State, and he served until his death.

The Amherst Political Union (APU) is a student debating club at Amherst College. Founded in 1939 by Robert Morgenthau '41 and Richard Wilbur '42 and re-founded in the spring of 2010, the club aims to bring speakers on contemporary political thought to Amherst in a nonpartisan and unbiased manner.

Samuel Eusebius McCorkle was a pioneer Presbyterian preacher, teacher, advocate for public and private education in North Carolina, and the interceptor and progenitor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who first promoted the idea of establishing a university in the state.

"The Rising Glory of America" is a poem written by "Poet of the Revolution" Philip Freneau with a debated but likely minimal level of involvement from "not quite a Founding Father" Hugh Henry Brackenridge of western Pennsylvania. The poem was first read at their graduation from the College of New Jersey in 1771. There were two versions published, one before and one after the American Revolutionary War. It was mildly influential in describing a newfound sense of American national identity.

References

- ↑ For alternative title, see Leary, Lewis "Notes and Documents: Father Bombo's Pilgrimage," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 66 (1942): 459–478. p. 459.

- ↑ See Davidson, Cathy N. Revolution and the Word: The Rise of the Novel in America (Expanded Edition). Oxford UP, 2004. p. 155. See also Bell, Michael D. Introduction. Father Bombo's Pilgrimage to Mecca. Princeton U Library, 1975. p. ix.

- ↑ Philbrick, Thomas. "Review: Father Bombo's Pilgrimage to Mecca." Early American Literature 10.3 (1975): 314–316. p. 314.

- ↑ Bell, p. x.

- 1 2 Bell, p. xi.

- 1 2 Freneau & Brackenridge, Father Bombo's Pilgrimage to Mecca, Princeton U Library, 1975. p. 7.

- ↑ Freneau 1975, pp. 11, 8.

- ↑ Freneau 1975, p. 92.

- ↑ Leary, p. 459. Bell, p. xi.

- ↑ Bell, p. xii, n.7.

- ↑ Bell, p. xiii.

- ↑ Bell, p. xxiii.

- ↑ The Norton Anthology of American Literature, Fifth Edition, New York: Norton & Company, 1998. p. 807.

- ↑ For example, see Freneau 1975, p. 95.

- ↑ Freneau 1975, p. 23.

- ↑ Bell, p. xvii.

- ↑ See Malini Johar Schueller, U.S Orientalisms: Race, Nation, and Gender in Literature, 1790–1890, Ann Arbor: U Michigan Press p. 1998. p. 24.

- ↑ For examples, see Freneau 1975, p. 19, 21. See also Bell, p. xxix.

- ↑ For the Orientalized rhetoric surrounding a dispute between Harvard's students and administration, see Cohen, Sheldon, "The Turkish Tyranny," The New England Quarterly. 47.4 (1974): 564–583. See also Marr, Timothy, The Cultural Roots of American Islamicism, Cambridge UP, 2006. pp. 20–34.