Related Research Articles

HIV-positive people, seropositive people or people who live with HIV are people infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus which if untreated may progress to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

HIV is recognized as a health concern in Pakistan with the number of cases growing. Moderately high drug use and lack of acceptance that non-marital sex is common in the society have allowed the HIV epidemic to take hold in Pakistan, mainly among injecting drug users (IDU), male, female and transvestite sex workers as well as the repatriated migrant workers. HIV infection can lead to AIDS that may become a major health issue.

Since the first HIV/AIDS case in the Lao People's Democratic Republic (PDR) was identified in 1990, the number of infections has continued to grow. In 2005, UNAIDS estimated that 3,700 people in Lao PDR were living with HIV.

HIV/AIDS in Eswatini was first reported in 1986 but has since reached epidemic proportions. As of 2016, Eswatini had the highest prevalence of HIV among adults aged 15 to 49 in the world (27.2%).

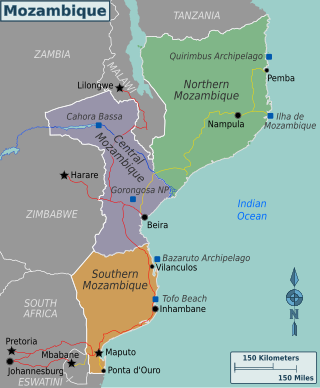

Mozambique is a country particularly hard-hit by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. According to 2008 UNAIDS estimates, this southeast African nation has the 8th highest HIV rate in the world. With 1,600,000 Mozambicans living with HIV, 990,000 of which are women and children, Mozambique's government realizes that much work must be done to eradicate this infectious disease. To reduce HIV/AIDS within the country, Mozambique has partnered with numerous global organizations to provide its citizens with augmented access to antiretroviral therapy and prevention techniques, such as condom use. A surge toward the treatment and prevention of HIV/AIDS in women and children has additionally aided in Mozambique's aim to fulfill its Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Nevertheless, HIV/AIDS has made a drastic impact on Mozambique; individual risk behaviors are still greatly influenced by social norms, and much still needs to be done to address the epidemic and provide care and treatment to those in need.

With less than 0.1 percent of the population estimated to be HIV-positive, Bangladesh is a low HIV-prevalence country.

UNAIDS has said that HIV/AIDS in Indonesia is one of Asia's fastest growing epidemics. In 2010, it is expected that 5 million Indonesians will have HIV/AIDS. In 2007, Indonesia was ranked 99th in the world by prevalence rate, but because of low understanding of the symptoms of the disease and high social stigma attached to it, only 5-10% of HIV/AIDS sufferers actually get diagnosed and treated. According to the a census conducted in 2019, it is counted that 640,443 people in the country are living with HIV. The adult prevalence for HIV/ AIDS in the country is 0.4%. Indonesia is the country in Southeast Asia to have the most number of recorded people living with HIV while Thailand has the highest adult prevalence.

The first HIV/AIDS cases in Nepal were reported in 1988. The HIV epidemic is largely attributed to sexual transmissions and account for more than 85% of the total new HIV infections. Coinciding with the outbreak of civil unrest, there was a drastic increase in the new cases in 1996. The infection rate of HIV/AIDS in Nepal among the adult population is estimated to be below the 1 percent threshold which is considered "generalized and severe". However, the prevalence rate masks a concentrated epidemic among at-risk populations such as female sex workers (FSWs), male sex workers (MSWs), injecting drug users (IDUs), men who have sex with men (MSM), Transgender Groups (TG), migrants and male labor migrants (MLMs) as well as their spouses. Socio-Cultural taboos and stigmas that pose an issue for open discussion concerning sex education and sex habits to practice has manifest crucial role in spread of HIV/AIDS in Nepal. With this, factors such as poverty, illiteracy, political instability combined with gender inequality make the tasks challenging.

The Philippines has one of the lowest rates of infection of HIV/AIDS, yet has one of the fastest growing number of cases worldwide. The Philippines is one of seven countries with growth in number of cases of over 25%, from 2001 to 2009.

Since HIV/AIDS was first reported in Thailand in 1984, 1,115,415 adults had been infected as of 2008, with 585,830 having died since 1984. 532,522 Thais were living with HIV/AIDS in 2008. In 2009 the adult prevalence of HIV was 1.3%. As of 2016, Thailand had the highest prevalence of HIV in Southeast Asia at 1.1 percent, the 40th highest prevalence of 109 nations.

Cases of HIV/AIDS in Peru are considered to have reached the level of a concentrated epidemic.

The Dominican Republic has a 0.7 percent prevalence rate of HIV/AIDS, among the lowest percentage-wise in the Caribbean region. However, it has the second most cases in the Caribbean region in total web|url=http://www.avert.org/caribbean-hiv-aids-statistics.htm |title=Caribbean HIV & AIDS Statistics|date=21 July 2015}}</ref> with an estimated 46,000 HIV/AIDS-positive Dominicans as of 2013.

HIV/AIDS in El Salvador has a less than 1 percent prevalence of the adult population reported to be HIV-positive. El Salvador therefore is a low-HIV-prevalence country. The virus remains a significant threat in high-risk communities, such as commercial sex workers (CSWs) and men who have sex with men (MSM).

Nicaragua has 0.2 percent of the adult population estimated to be HIV-positive. Nicaragua has one of the lowest HIV prevalence rates in Central America.

With less than 1 percent of the population estimated to be HIV-positive, Egypt is a low-HIV-prevalence country. However, between the years 2006 and 2011, HIV prevalence rates in Egypt increased tenfold. Until 2011, the average number of new cases of HIV in Egypt was 400 per year. But, in 2012 and 2013 it increased to about 600 new cases and in 2014 it reached 880 new cases per year. According to UNAIDS 2016 statistics, there are about 11,000 people currently living with HIV in Egypt. The Ministry of Health and Population reported in 2020 over 13,000 Egyptians are living with HIV/AIDS. However, unsafe behaviors among most-at-risk populations and limited condom usage among the general population place Egypt at risk of a broader epidemic.

With 1.28 percent of the adult population estimated by UNAIDS to be HIV-positive in 2006, Papua New Guinea has one of the most serious HIV/AIDS epidemics in the Asia-Pacific subregion. Although this new prevalence rate is significantly lower than the 2005 UNAIDS estimate of 1.8 percent, it is considered to reflect improvements in surveillance rather than a shrinking epidemic. Papua New Guinea accounts for 70 percent of the subregion's HIV cases and is the fourth country after Thailand, Cambodia, and Burma to be classified as having a generalized HIV epidemic.

Vietnam faces a concentrated HIV epidemic among high-risk groups, including sex workers, and intravenous drug users. There are cases of HIV/AIDS in all provinces of Vietnam, though low testing rates make it difficult to estimate how prevalent the disease is. The known rates among high-risk groups are high enough that there is a risk of HIV/AIDS rates increasing among the general population as well. People who are HIV+ face intense discrimination in Vietnam, which does not offer legal protections to those living with the condition. Stigma, along with limited funding and human research, make the epidemic difficult to control.

Since reports of emergence and spread of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the United States between the 1970s and 1980s, the HIV/AIDS epidemic has frequently been linked to gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) by epidemiologists and medical professionals. It was first noticed after doctors discovered clusters of Kaposi's sarcoma and pneumocystis pneumonia in homosexual men in Los Angeles, New York City, and San Francisco in 1981. The first official report on the virus was published by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) on June 5, 1981, and detailed the cases of five young gay men who were hospitalized with serious infections. A month later, The New York Times reported that 41 homosexuals had been diagnosed with Kaposi's sarcoma, and eight had died less than 24 months after the diagnosis was made.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Kouyoumjian, SP., Mumtaz, GR., Hilmi, N., Zidouh, A., El Rhilani, H., Alami, K., Bennani, A., Gouws, E., Ghys, PD., & Abu-Raddad, LJ. (2013). "The epidemiology of HIV infection in Morocco: systematic review and data synthesis". International Journal of STD & AIDS. 24, 507-516.

- 1 2 3 4 Mumtaz, GR., Kouyoumjian, SP., Hilmi, N., Zidouh, A., El Rhilani, H., Alami, K., Bennani, A., Gouws, E., Ghyds, PD., & Abu-Raddad, LJ. (2013). The distribution of new HIV infections by mode of exposure in Morocco. Sex Transm Infect. 83, iii49–iii56.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Loukid, M., Abadie, A., Henry, E., Hilali, M. K., Fugon, L., Rafif, N., ... & Préau, M. (2014). "Factors associated with HIV status disclosure to one’s steady sexual partner in PLHIV in Morocco". Journal of Community Health, 39(1), 50–59.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Remien, R. H., Chowdhury, J., Mokhbat, J. E., Soliman, C., El Adawy, M., & El-Sadr, W. (2009). "Gender and care: access to HIV testing, care and treatment". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 51 (Suppl 3), S106.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kouyoumjian, SP., El Rhilani, H., Latific, A., El Kattani, A., Chemaitelly, H., Alami, K., Bennani, A., & Abu-Raddad, LJ. (2018). "Mapping of new HIV infections in Morocco and impact of select interventions". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 68, 4-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Morocco". UNAIDS. Retrieved 2021-12-12.

- 1 2 3 4 Henry, E., Bernier, A., Lazar, F., Matamba, G., Loukid, M., Bonifaz, C., ... & Préau, M. (2015). "'Was it a mistake to tell others that you are infected with HIV?': Factors associated with regret following HIV disclosure among people living with HIV in five countries (Mali, Morocco, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ecuador and Romania). Results from a community-based research". AIDS and Behavior, 19 (2), 311–321.