Human cannibalism is the act or practice of humans eating the flesh or internal organs of other human beings. A person who practices cannibalism is called a cannibal. The meaning of "cannibalism" has been extended into zoology to describe an individual of a species consuming all or part of another individual of the same species as food, including sexual cannibalism.

This article is about the spiritual beliefs, histories and practices in Kwakwaka'wakw mythology. The Kwakwaka'wakw are a group of Indigenous nations, numbering about 5,500, who live in the central coast of British Columbia on northern Vancouver Island and the mainland. Kwakwaka'wakw translates into "Kwak'wala speaking tribes." However, the tribes are single autonomous nations and do not view themselves collectively as one group.

A potlatch is a gift-giving feast practiced by Indigenous Peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of Canada and the United States, among whom it is traditionally the primary governmental institution, legislative body, and economic system. This includes the Heiltsuk, Haida, Nuxalk, Tlingit, Makah, Tsimshian, Nuu-chah-nulth, Kwakwaka'wakw, and Coast Salish cultures. Potlatches are also a common feature of the peoples of the Interior and of the Subarctic adjoining the Northwest Coast, although mostly without the elaborate ritual and gift-giving economy of the coastal peoples.

The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw, also known as the Kwakiutl are Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Their current population, according to a 2016 census, is 3,665. Most live in their traditional territory on northern Vancouver Island, nearby smaller islands including the Discovery Islands, and the adjacent British Columbia mainland. Some also live outside their homelands in urban areas such as Victoria and Vancouver. They are politically organized into 13 band governments.

Laich-kwil-tach, is the Anglicization of the Kwak'wala autonomy by the "Southern Kwakiutl" people of Quadra Island and Campbell River in British Columbia, Canada. There are today two main groups : the Wei Wai Kai and Wei Wai Kum just across on the Vancouver Island "mainland" in the town of Campbell River. In addition to these two main groups there are the Kwiakah originally from Phillips Arm and Frederick Arm and the Discovery Islands, the Tlaaluis (Laa'luls) between Bute and Loughborough Inlets—after a great war between the Kwakiutl and the Salish peoples they were so reduced in numbers that they joined the Kwiakah—and the Walitsima / Walitsum Band of Salmon River.

Cannibalism, the act of eating human flesh, is a recurring theme in popular culture, especially within the horror genre, and has been featured in a range of media that includes film, television, literature, music and video games. Cannibalism has been featured in various forms of media as far back as Greek mythology. The frequency of this theme has led to cannibal films becoming a notable subgenre of horror films. The subject has been portrayed in various different ways and is occasionally normalized. The act may also be used in media as a means of survival, an accidental misfortune, or an accompaniment to murder. Examples of prominent artists who have worked with the topic of cannibalism include William Shakespeare, Voltaire, Bret Easton Ellis, and Herschell Gordon Lewis.

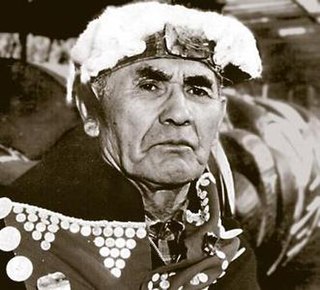

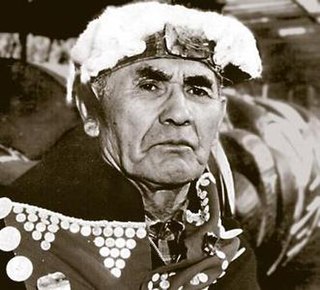

Chief Mungo Martin or Nakapenkem, Datsa, was an important figure in Northwest Coast style art, specifically that of the Kwakwaka'wakw Aboriginal people who live in the area of British Columbia and Vancouver Island. He was a major contributor to Kwakwaka'wakw art, especially in the realm of wood sculpture and painting. He was also known as a singer and songwriter.

Dzunuḵ̓wa, also Tsonoqua, Tsonokwa, Basket Ogress, is a figure in Kwakwaka'wakw mythology and Nuu-chah-nulth mythology.

Bakwas is one of the supernatural spirits of the Kwakwaka'wakw people of coastal British Columbia. He is often called "wild man of the woods." He eats ghost food out of cockle shells and tries to offer this to living humans who are stranded in the woods, in order to bring them over to the ghost world. If the human were to eat this food, it would turn them into a being like the bakwas. He lives in an invisible house in the forest and the spirits of the drowned congregate there. In some myths he is described as the consort of dzunukwa, and the father of her children.

Tlugwe, in the Kwak'wala language of the Kwakwaka'wakw people in British Columbia, means 'supernatural treasure'. Tlugwe are one of the most important features of Kwakwaka'wakw religious practices.

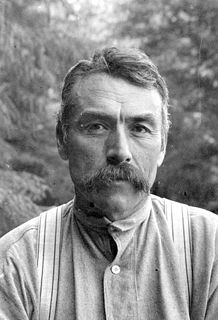

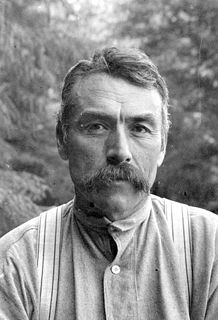

George Hunt (Tlingit) was a consultant to the American anthropologist Franz Boas; through his contributions he is considered a linguist and ethnologist in his own right. He was Tlingit-English by birth and learned both those languages. Growing up with his parents at Fort Rupert, British Columbia in Kwakwaka'wakw territory, he learned their language and culture as well. Through marriage and adoption he became an expert on the traditions of the Kwakwaka'wakw of coastal British Columbia.

The sisiutl is a legendary creature found in many of the cultures of the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. It is typically depicted as a double-headed serpent with fish qualities, sometimes with an additional central face of a supernatural being. The sisuitl features prominently in Pacific Northwest art, dances and songs. The sisuitl is closely associated with shamans because both are seen as mediators between the natural and supernatural worlds.

Exocannibalism, as opposed to endocannibalism, is the consumption of flesh outside one's close social group—for example, eating one's enemy. When done ritually, it has been associated with being a means of imbibing valued qualities of the victim or as an act of final violence against the deceased in the case of sociopathy, as well as a symbolic expression of the domination of an enemy in warfare. Such practices have been documented in cultures including the Aztecs from Mexico, the Carib and the Tupinambá from South America.

Willie Seaweed (1873–1967) was a Kwakwaka'wakw chief and wood carver from Canada. He was considered a master Northwest Coast Indian artist who is remembered for his technical artistic style and protection of traditional native ceremonies during the Canadian potlatch ceremony ban. Today, Seaweed's work can be found in cultural centers and corporations, art museums, natural history museums, and private collections. Some pieces are still in use by the Nak'waxda'xw tribe.

A transformation mask, also known as an opening mask, is a type of mask used by indigenous people of the Northwest Coast and Alaska in ritual dances. These masks usually depict an outer, animal visage, which the performer can open by pulling a string to reveal an inner human face carved in wood to symbolize the wearer moving from the natural world to a supernatural realm. Northwest coast peoples generally use them in potlatches to illustrate myths, while they are used by Alaska natives for shamanic rituals.

Kwakwaka'wakw art describes the art of the Kwakwaka'wakw peoples of British Columbia. It encompasses a wide variety of woodcarving, sculpture, painting, weaving and dance. Kwakwaka'wakw arts are exemplified in totem poles, masks, wooden carvings, jewelry and woven blankets. Visual arts are defined by simplicity, realism, and artistic emphasis. Dances are observed in the many rituals and ceremonies in Kwakwaka'wakw culture. Much of what is known about Kwakwaka'wakw art comes from oral history, archeological finds in the 19th century, inherited objects, and devoted artists educated in Kwakwaka'wakw traditions.

Dantsikw are dance props of the first nations Kwakwaka'wakwa people of British Columbia, Canada. These boards were employed during the Winter Ceremonials (Tseka). In the Tuxwid warrior ceremony, the initiates would demonstrate supernatural powers granted by Winalagilis by summoning Dantsikw power boards from underground, and making them disappear again. This act commemorates Winalagalis' supernatural canoe that could travel underground.

Winalagalis is a war god of the Kwakwaka'wakw native people of British Columbia. He travels the world, making war. Winalagilis comes from North (underworld) to winter with the Kwakwaka'wakw. Winalagalis is the bringer and ruler of Tseka, and imbues red cedar bark with supernatural power.

Kwakwaka'wakw music is a sacred and ancient art of the Kwakwaka'wakw peoples that has been practiced for thousands of years. The Kwakwaka'wakw are a collective of twenty-five nations of the Wakashan language family who altogether form part of a larger identity comprising the Indigenous Peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, located in what is known today as British Columbia, Canada.