The Winnipeg Art Gallery (WAG) is an art museum in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Its permanent collection includes over 24,000 works from Canadian, Indigenous Canadian, and international artists. The museum also holds the world's largest collection of Inuit art. In addition to exhibits for its collection, the museum has organized and hosted a number of travelling arts exhibitions. Its building complex consists of a main building that includes 11,000 square metres (120,000 sq ft) of indoor space and the adjacent 3,700-square-metre (40,000 sq ft) Qaumajuq building.

Jessie Oonark, was a prolific and influential Inuk artist of the Utkuhiksalingmiut Utkuhiksalingmiut whose wall hangings, prints and drawings are in major collections including the National Gallery of Canada.

Kenojuak Ashevak, was a Canadian Inuk artist. She was born on October 3, 1927 at Camp Kerrasak on southern Baffin Island, and died on January 8, 2013 in Cape Dorset, Nunavut. Known primarily for her drawings as a graphic artist, she also had a diverse artistic experience, making sculpture and engraving and working with textiles and also on stained glass. She is celebrated as a leading figure of modern Inuit art and one of Canada's preeminent artists and cultural icons. Part of a pioneering generation of Arctic creators, her career spanned more than five decades. She made graphic art, drawings and prints in stone cut, lithography and etching, beloved by the public, museums and collectors alike. Kenojuak has mainly painted animals in fantastical, brightly-colored aspects, but also landscapes and scenes of everyday life, in a desire to represent them in a unique aesthetic, making them beautiful by her own standards, and conveying a real spirit of happiness and positivity. She has an intuitive and sensitive way of working : she begins her works without having a clear idea of the final result, letting herself be guided by her intuition and her own perception of aestheticism through colors and shapes. She painted throughout her life, never ceasing to seek out new techniques to renew her artistic creation. At the beginning of her life, her fantastical, seemingly simple works became more complex over time, taking on a more technical aspect. At the end of her life, the artist returned to simpler, more singular forms and even brighter colors.

Kinngait, known as Cape Dorset until 27 February 2020, is an Inuit hamlet located on Dorset Island near Foxe Peninsula at the southern tip of Baffin Island in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada.

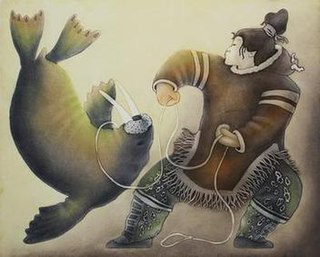

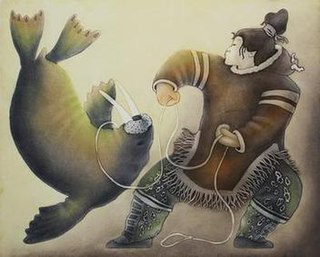

Inuit art, also known as Eskimo art, refers to artwork produced by Inuit, that is, the people of the Arctic previously known as Eskimos, a term that is now often considered offensive. Historically, their preferred medium was walrus ivory, but since the establishment of southern markets for Inuit art in 1945, prints and figurative works carved in relatively soft stone such as soapstone, serpentinite, or argillite have also become popular.

William Noah is a former territorial level politician and artist. He served as a member of the Northwest Territories Legislature from 1979 until 1982.

Pudlo Pudlat, was a Canadian Inuit artist whose preferred medium was a combination of acrylic wash and coloured pencils. His works are in the collections of most Canadian museums. At his death in 1992, Pudlo left a body of work that included more than 4000 drawings and 200 prints.

Germaine Arnaktauyok is an Inuk printmaker, painter, and drawer originating from the Igloolik area of Nunavut, then the Northwest Territories. Arnaktauyok drew at an early age with any source of paper she could find.

Pitaloosie Saila was a Canadian Inuk graphic artist who predominantly made drawings and lithograph prints. Saila's work often explores themes such as family, shamanism, birds, and her personal life experiences as an Inuk woman. Her work has been displayed in over 150 exhibitions nationally and internationally, such as in the acclaimed Isumavut exhibition called "The Artistic Expression of Nine Cape Dorset Women". In 2004, Pitaloosie Saila and her well-known husband and sculptor Pauta Saila were both inducted into the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts.

Sheila Butler is an American-Canadian visual artist and retired professor, now based in Winnipeg, Manitoba. She is a founding member of Mentoring Artists for Women's Art in Winnipeg, Manitoba and the Sanavik Inuit Cooperative in Baker Lake, Nunavut. She is a fellow of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts.

Victoria Mamnguqsualuk (1930-2016) was one of the best-known Canadian Inuit artists of her generation.

Ulayu Pingwartok was a Canadian Inuk artist known for drawings of domestic scenes and nature.

Elizabeth Angrnaqquaq (1916–2003) was an innovative Canadian Inuk textile artist active from the 1970s to early 2000s. Angnaqquaq's work explores textile creations while experimenting with non-traditional methods. Her style has been described as painterly for the way in which she fills the space between her figures and animals with embroidery.

Eleeshushe Parr was an Inuk graphic artist and sculptor, from the Kingnait area, who produced over 1,160 drawings. Her work has been exhibited in Canada, the United States, and Sweden.

Elisapee Ishulutaq was a self-taught Inuk artist, specialising in drawing and printmaking. Ishulutaq participated in the rise of print and tapestry making in Pangnirtung and was a co-founder of the Uqqurmiut Centre for Arts & Crafts, which is both an economic and cultural mainstay in Pangnirtung. Ishulutaq was also a community elder in the town of Pangnirtung. Ishulutaq's work has been shown in numerous institutions, including the Marion Scott Gallery in Vancouver, the Winnipeg Art Gallery and the National Gallery of Canada.

Ohotaq (Oqutaq) Mikkigak was a Cape Dorset based Inuk artist from southern Baffin Island. Mikkigak was involved with Cape Dorset printmaking in the program's early years, providing drawn designs for printing. Many of his works were printed and featured in the studio's annual collections, including Eskimo Fox Trapper and three pieces used in the Cape Dorset Studio's 40th anniversary collection. Mikkigak's work has also been included in of over twenty group exhibitions and was the subject of multiple solo exhibitions, including a show held by Feheley Fine Arts called Ohotaq Mikkigak: Imagined Landscapes.

Innukjuakju Pudlat (1913–1972), alternatively known as Inukjurakju, Innukjuakjuk, Inujurakju, Innukjuakjuk Pudlat, Inukjurakju Pudlat, Innukyuarakjuke Pudlat, or Innukjuarakjuke Pudlat, was an Inuk artist who worked primarily in drawing and printmaking. During her artistic career she worked with the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative in Cape Dorset, Nunavut.

The West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative, also known as the Kinngait Co-operative is an Inuit co-operative in Kinngait, Nunavut best known for its activities in buying, producing and selling Inuit artworks. The co-operative is part of Arctic Co-operatives Limited, a group of locally owned businesses that provide fundamental services in the Canadian north. The co-operative sets prices for the sale of its member's works, pays the artists in advance and shares its profits with its members.

Kiakshuk was a Canadian Inuit artist who worked both in sculpture and printmaking. Kiakshuk began printmaking in his seventies and, is most commonly praised for creating “real Eskimo pictures” that relate traditional Inuit life and mythology.

William H. Lobchuk, known as Bill Lobchuk was one of the first people in Canada to found a printshop which made printmaking facilities available to contemporary artists. In 1968 he opened the Screen Shop at 50 Princess Street in Winnipeg with partner Len Anthony, which led to the founding of The Grand Western Canadian Screen Shop in 1973. It was the first print shop of its kind in Western Canada and a focus of printmaking production and distribution for artists, both in the Prairies and Canada-wide.