In commerce, supply chain management (SCM) deals with a system of procurement, operations management, logistics and marketing channels so that the raw materials can be converted into a finished product and delivered to the end customer. A more narrow definition of the supply chain management is the "design, planning, execution, control, and monitoring of supply chain activities with the objective of creating net value, building a competitive infrastructure, leveraging worldwide logistics, synchronising supply with demand and measuring performance globally".This can include the movement and storage of raw materials, work-in-process inventory, finished goods, and end to end order fulfilment from the point of origin to the point of consumption. Interconnected, interrelated or interlinked networks, channels and node businesses combine in the provision of products and services required by end customers in a supply chain.

Logistics is a part of supply chain management that deals with the efficient forward and reverse flow of goods, services, and related information from the point of origin to the point of consumption according to the needs of customers. Logistics management is a component that holds the supply chain together. The resources managed in logistics may include tangible goods such as materials, equipment, and supplies, as well as food and other consumable items.

Material requirements planning (MRP) is a production planning, scheduling, and inventory control system used to manage manufacturing processes. Most MRP systems are software-based, but it is possible to conduct MRP by hand as well.

Inventory or stock refers to the goods and materials that a business holds for the ultimate goal of resale, production or utilisation.

The theory of constraints (TOC) is a management paradigm that views any manageable system as being limited in achieving more of its goals by a very small number of constraints. There is always at least one constraint, and TOC uses a focusing process to identify the constraint and restructure the rest of the organization around it. TOC adopts the common idiom "a chain is no stronger than its weakest link". That means that organizations and processes are vulnerable because the weakest person or part can always damage or break them, or at least adversely affect the outcome.

Lean manufacturing is a production method aimed primarily at reducing times within the production system as well as response times from suppliers and to customers. It is closely related to another concept called just-in-time manufacturing. Just-in-time manufacturing tries to match production to demand by only supplying goods which have been ordered and focuses on efficiency, productivity and reduction of "wastes" for the producer and supplier of goods. Lean manufacturing adopts the just-in-time approach and additionally focuses on reducing cycle, flow and throughput times by further eliminating activities which do not add any value for the customer. Lean manufacturing also involves people who work outside of the manufacturing process, such as in marketing and customer service.

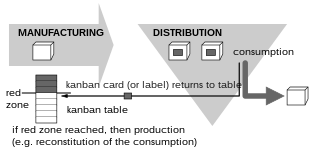

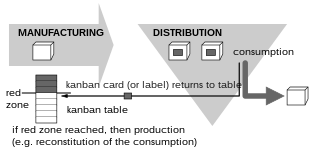

Kanban is a scheduling system for lean manufacturing. Taiichi Ohno, an industrial engineer at Toyota, developed kanban to improve manufacturing efficiency. The system takes its name from the cards that track production within a factory. Kanban is also known as the Toyota nameplate system in the automotive industry.

Operations management is an area of management concerned with designing and controlling the process of production and redesigning business operations in the production of goods or services. It involves the responsibility of ensuring that business operations are efficient in terms of using as few resources as needed and effective in meeting customer requirements.

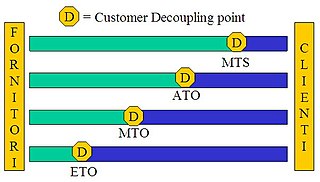

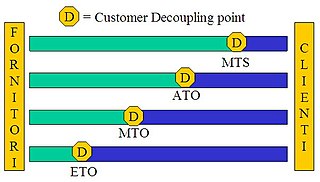

A lead time is the latency between the initiation and completion of a process. For example, the lead time between the placement of an order and delivery of new cars by a given manufacturer might be between 2 weeks and 6 months, depending on various particularities. One business dictionary defines "manufacturing lead time" as the total time required to manufacture an item, including order preparation time, queue time, setup time, run time, move time, inspection time, and put-away time. For make-to-order products, it is the time between release of an order and the production and shipment that fulfill that order. For make-to-stock products, it is the time taken from the release of an order to production and receipt into finished goods inventory.

Remanufacturing is "the rebuilding of a product to specifications of the original manufactured product using a combination of reused, repaired and new parts". It requires the repair or replacement of worn out or obsolete components and modules. Parts subject to degradation affecting the performance or the expected life of the whole are replaced. Remanufacturing is a form of a product recovery process that differs from other recovery processes in its completeness: a remanufactured machine should match the same customer expectation as new machines.

Safety stock is a term used by logisticians to describe a level of extra stock that is maintained to mitigate risk of stockouts caused by uncertainties in supply and demand. Adequate safety stock levels permit business operations to proceed according to their plans. Safety stock is held when uncertainty exists in demand, supply, or manufacturing yield, and serves as an insurance against stockouts.

Takt time, or simply takt, is a manufacturing term to describe the required product assembly duration that is needed to match the demand. Often confused with cycle time, takt time is a tool used to design work and it measures the average time interval between the start of production of one unit and the start of production of the next unit when items are produced sequentially. For calculations, it is the time to produce parts divided by the number of parts demanded in that time interval. The takt time is based on customer demand; if a process or a production line are unable to produce at takt time, either demand leveling, additional resources, or process re-engineering is needed to ensure on-time delivery.

Build to Order is a production approach where products are not built until a confirmed order for products is received. Thus, the end consumer determines the time and number of produced products. The ordered product is customized, meeting the design requirements of an individual, organization or business. Such production orders can be generated manually, or through inventory/production management programs. BTO is the oldest style of order fulfillment and is the most appropriate approach used for highly customized or low volume products. Industries with expensive inventory use this production approach. Moreover, "Made to order" products are common in the food service industry, such as at restaurants.

Order fulfillment is in the most general sense the complete process from point of sales inquiry to delivery of a product to the customer. Sometimes, it describes the more narrow act of distribution or the logistics function. In the broader sense, it refers to the way firms respond to customer orders.

Cellular manufacturing is a process of manufacturing which is a subsection of just-in-time manufacturing and lean manufacturing encompassing group technology. The goal of cellular manufacturing is to move as quickly as possible, make a wide variety of similar products, while making as little waste as possible. Cellular manufacturing involves the use of multiple "cells" in an assembly line fashion. Each of these cells is composed of one or multiple different machines which accomplish a certain task. The product moves from one cell to the next, each station completing part of the manufacturing process. Often the cells are arranged in a "U-shape" design because this allows for the overseer to move less and have the ability to more readily watch over the entire process. One of the biggest advantages of cellular manufacturing is the amount of flexibility that it has. Since most of the machines are automatic, simple changes can be made very rapidly. This allows for a variety of scaling for a product, minor changes to the overall design, and in extreme cases, entirely changing the overall design. These changes, although tedious, can be accomplished extremely quickly and precisely.

Field inventory management commonly known as inventory management is the function of understanding the stock mix of a company and the different demands on that stock. The demands are influenced by both external and internal factors and are balanced by the creation of purchase order requests to keep supplies at a reasonable or prescribed level. Inventory management is important for every other business enterprise.

Production leveling, also known as production smoothing or – by its Japanese original term – heijunka (平準化), is a technique for reducing the mura (unevenness) which in turn reduces muda (waste). It was vital to the development of production efficiency in the Toyota Production System and lean manufacturing. The goal is to produce intermediate goods at a constant rate so that further processing may also be carried out at a constant and predictable rate.

Backflush accounting is a subset of management accounting focused on types of "postproduction issuing;" It is a product costing approach, used in a Just-In-Time (JIT) operating environment, in which costing is delayed until goods are finished. Backflush accounting delays the recording of costs until after the events have taken place, then standard costs are used to work backwards to 'flush' out the manufacturing costs. The result is that detailed tracking of costs is eliminated. Journal entries to inventory accounts may be delayed until the time of product completion or even the time of sale, and standard costs are used to assign costs to units when journal entries are made. Backflushing transaction has two steps: one step of the transaction reports the produced part which serves to increase the quantity on-hand of the produced part and a second step which relieves the inventory of all the component parts. Component part numbers and quantities-per are taken from the standard bill of material (BOM). This represents a huge saving over the traditional method of a) issuing component parts one at a time, usually to a discrete work order, b) receiving the finished parts into inventory, and c) returning any unused components, one at a time, back into inventory.

Demand Flow Technology (DFT) is a strategy for defining and deploying business processes in a flow, driven in response to customer demand. DFT is based on a set of applied mathematical tools that are used to connect processes in a flow and link it to daily changes in demand. DFT represents a scientific approach to flow manufacturing for discrete production. It is built on principles of demand pull where customer demand is the central signal to guide factory and office activity in the daily operation. DFT is intended to provide an alternative to schedule-push manufacturing which primarily uses a sales plan and forecast to determine a production schedule.

Merge-in-transit (MIT) is a distribution method in which several shipments from suppliers originating at different locations are consolidated into one final customer delivery. This removes the need for distribution warehouses in the supply chain, allowing customers to receive complete deliveries for their orders. Under a merge-in-transit system, merge points replace distribution warehouse. In today's global market, merge-in-transit is progressively being used in telecommunications and electronic industries. These industries are usually dynamic and flexible, in which products have been developed and changed rapidly.

Stephan M. Wagner and Victor Silveira-Camargos, 2009, Decision model for the application of just-in-sequence, in: Decision Sciences Institute Proceedings of the 40th annual conference, New Orleans, USA.