Related Research Articles

The Malleus Maleficarum, usually translated as the Hammer of Witches, is the best known treatise about witchcraft. It was written by the German Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer and first published in the German city of Speyer in 1486. Some describe it as the compendium of literature in demonology of the 15th century. Kramer presented his own views as the Roman Catholic Church's position.

Francis Hutcheson was an Irish philosopher known as one of the founding fathers of the Scottish Enlightenment. Born in Ulster to a family of Scottish Presbyterians, he was Professor of Moral Philosophy at Glasgow University and is remembered as author of A System of Moral Philosophy.

Kindness is a type of behavior marked by acts of generosity, consideration, rendering assistance, or concern for others, without expecting praise or reward in return. It is a subject of interest in philosophy, religion, and psychology.

Emotivism is a meta-ethical view that claims that ethical sentences do not express propositions but emotional attitudes. Hence, it is colloquially known as the hurrah/boo theory. Influenced by the growth of analytic philosophy and logical positivism in the 20th century, the theory was stated vividly by A. J. Ayer in his 1936 book Language, Truth and Logic, but its development owes more to C. L. Stevenson.

Ethical subjectivism is the meta-ethical view which claims that:

- Ethical sentences express propositions.

- Some such propositions are true.

- The truth or falsity of such propositions is ineliminably dependent on the attitudes of people.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments is a 1759 book by Adam Smith. It provided the ethical, philosophical, economic, and methodological underpinnings to Smith's later works, including The Wealth of Nations (1776), Essays on Philosophical Subjects (1795), and Lectures on Justice, Police, Revenue, and Arms (1763).

Joel Feinberg was an American political and legal philosopher. He is known for his work in the fields of ethics, action theory, philosophy of law, and political philosophy as well as individual rights and the authority of the state. Feinberg was one of the most influential figures in American jurisprudence of the last fifty years.

An imprimatur is a declaration authorizing publication of a book. The term is also applied loosely to any mark of approval or endorsement. The imprimatur rule in the Catholic Church effectively dates from the dawn of printing, and is first seen in the printing and publishing centres of Germany and Venice; many secular states or cities began to require registration or approval of published works around the same time, and in some countries such restrictions still continue, though the collapse of the Soviet bloc has reduced their number.

Supererogation is the performance of more than is asked for; the action of doing more than duty requires. In ethics, an act is supererogatory if it is good but not morally required to be done. It refers to an act that is more than is necessary, when another course of action—involving less—would still be an acceptable action. It differs from a duty, which is an act wrong not to do, and from acts morally neutral. Supererogation may be considered as performing above and beyond a normative course of duty to further benefits and functionality.

In philosophy, moral responsibility is the status of morally deserving praise, blame, reward, or punishment for an act or omission in accordance with one's moral obligations. Deciding what counts as "morally obligatory" is a principal concern of ethics.

Kantian ethics refers to a deontological ethical theory developed by German philosopher Immanuel Kant that is based on the notion that "I ought never to act except in such a way that I could also will that my maxim should become a universal law." It is also associated with the idea that "it is impossible to think of anything at all in the world, or indeed even beyond it, that could be considered good without limitation except a good will." The theory was developed in the context of Enlightenment rationalism. It states that an action can only be moral if it is motivated by a sense of duty, and its maxim may be rationally willed a universal, objective law.

An indifferent act is any action that is neither good nor evil.

Approbation, in Catholic canon law, is an act by which a bishop or other legitimate superior grants to an ecclesiastic the actual exercise of his ministry.

In criminal law, guilt is the state of being responsible for the commission of an offense. Legal guilt is entirely externally defined by the state, or more generally a "court of law". Being factually guilty of a criminal offense means that one has committed a violation of criminal law or performed all the elements of the offense set out by a criminal statute. The determination that one has committed that violation is made by an external body after the determination of the facts by a finder of fact or "factfinder" and is, therefore, as definitive as the record-keeping of the body. For instance, in the case of a bench trial, a judge acts as both the court of law and the factfinder, whereas in a jury trial, the jury is the trier of fact and the judge acts only as the trier of law.

Catholic moral theology is a major category of doctrine in the Catholic Church, equivalent to a religious ethics. Moral theology encompasses Catholic social teaching, Catholic medical ethics, sexual ethics, and various doctrines on individual moral virtue and moral theory. It can be distinguished as dealing with "how one is to act", in contrast to dogmatic theology which proposes "what one is to believe".

Moral rationalism, also called ethical rationalism, is a view in meta-ethics according to which moral principles are knowable a priori, by reason alone. Some prominent figures in the history of philosophy who have defended moral rationalism are Plato and Immanuel Kant. Perhaps the most prominent figure in the history of philosophy who has rejected moral rationalism is David Hume. Recent philosophers who have defended moral rationalism include Richard Hare, Christine Korsgaard, Alan Gewirth, and Michael Smith.

Natural morality refers to morality that is based on human nature, rather than acquired from societal norms or religious teachings. Charles Darwin's theory of evolution is central to many modern conceptions of natural morality, but the concept goes back at least to naturalism.

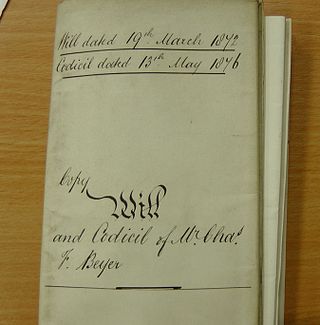

Dillwyn v Llewelyn [1862] is an 'English' land, probate and contract law case which established an example of proprietary estoppel at the testator's wish overturning his last Will and Testament; the case concerned land in Wales demonstrating the united jurisdiction of England and Wales.

Thawāb, Sawab, Hasanat or Ajr is an Arabic term meaning "reward". Specifically, in the context of an Islamic worldview, thawāb refers to spiritual merit or reward that accrues from the performance of good deeds and piety based on the guidance of the Quran and the Sunnah of Prophet Muhammad.

Tzachi Zamir is an Israeli philosopher and literary critic specialising in the philosophy of literature, the philosophy of theatre, and animal ethics. He is Professor of English and General & Comparative Literature at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

References

- Hodge, Charles. Systematic Theology - Volume II. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1940.