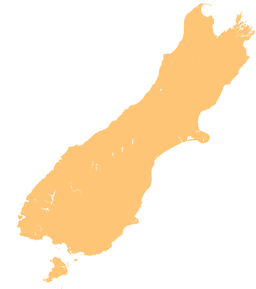

The South Island is the largest of the three major islands of New Zealand in surface area, the others being the smaller but more populous North Island and sparsely populated Stewart Island. It is bordered to the north by Cook Strait, to the west by the Tasman Sea, to the south by the Foveaux Strait and Southern Ocean, and to the east by the Pacific Ocean. The South Island covers 150,437 square kilometres (58,084 sq mi), making it the world's 12th-largest island, constituting 56% of New Zealand's land area. At low altitudes, it has an oceanic climate. The major centres are Christchurch, with a metropolitan population of 521,881, and the smaller Dunedin. The economy relies on agriculture, fishing, tourism, and general manufacturing and services.

Ngāi Tahu, or Kāi Tahu, is the principal Māori iwi (tribe) of the South Island. Its takiwā is the largest in New Zealand, and extends from the White Bluffs / Te Parinui o Whiti, Mount Mahanga and Kahurangi Point in the north to Stewart Island / Rakiura in the south. The takiwā comprises 18 rūnanga corresponding to traditional settlements. According to the 2018 census an estimated 74,082 people affiliated with the Kāi Tahu iwi.

Ōkārito Lagoon is a coastal lagoon on the West Coast of New Zealand's South Island. It is located 130 kilometres (81 mi) south of Hokitika, and covers an area of about 3,240 hectares (12.5 sq mi), making it the largest unmodified coastal wetland in New Zealand. It preserves a sequence of vegetation types from mature rimu forest through mānuka scrub to brackish water that has been lost in much of the rest of the West Coast. The settlement of Ōkārito is at the southern end of the lagoon.

Lake Kaniere is a glacial lake located on the West Coast of New Zealand's South Island. Nearly 200 metres (660 ft) deep, the lake is surrounded on three sides by mountains and mature rimu forest. It is regarded by many as the most beautiful of the West Coast lakes, and is a popular tourist and leisure destination.

Leeston is a town on the Canterbury Plains in the South Island of New Zealand. It is located 30 kilometres southwest of Christchurch, between the shore of Lake Ellesmere / Te Waihora and the mouth of the Rakaia River. The town is home to a growing number of services which have increased and diversified along with the population. Leeston has a supermarket, schools, churches, hospital, gym, cafes, restaurants, medical centre, pharmacy and post office. The Selwyn District Council currently has a service office in Leeston, after the headquarters was shifted to Rolleston.

The Ashley River is in the Canterbury region of New Zealand. It flows generally southeastwards for 65 kilometres (40 mi) before entering the Pacific Ocean at Waikuku Beach, Pegasus Bay north of Christchurch. The town of Rangiora is close to the south bank of the Ashley River. The river's official name was changed from Ashley River to the dual name Ashley River / Rakahuri by the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998.

Kāti Māmoe is a Māori iwi. Originally from the Heretaunga Plains of New Zealand's Hawke's Bay, they moved in the 16th century to the South Island which at the time was already occupied by the Waitaha.

Lake Mahinapua is a shallow lake on the West Coast of New Zealand's South Island. Once a lagoon at the mouth of the Hokitika River, it became a lake when the river shifted its course. Lake Māhinapua was the site of a significant battle between Ngāi Tahu and Ngāti Wairangi Māori, and is regarded by them as a sacred site where swimming and fishing are prohibited. In European times it was part of an inland waterway that carried timber and settlers between Hokitika and Ross until the building of the railway. Today it is protected as a scenic reserve for boating, camping, and hiking.

Lake Forsyth is a lake on the south-western side of Banks Peninsula in the Canterbury region of New Zealand, near the eastern end of the much larger Lake Ellesmere / Te Waihora. State Highway 75 to Akaroa and the Little River Rail Trail run along the north-western side of the lake.

Uruaokapuarangi was one of the great ocean-going, voyaging canoes that was used in the migrations that settled the South Island according to Māori tradition.

The Estuary of the Heathcote and Avon Rivers / Ihutai is the largest semi-enclosed shallow estuary in Canterbury and remains one of New Zealand's most important coastal wetlands. It is well known as an internationally important habitat for migratory birds, and it is an important recreational playground and educational resource. It was once highly valued for mahinga kai.

The Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998 is an act of Parliament passed in New Zealand relating to Ngāi Tahu, the principal Māori iwi (tribe) of Te Waipounamu the South Island. It was negotiated in part by Henare Rakiihia Tau. The documents in relation to the Ngāi Tahu land settlement claim are held at Tūranga, the main public library in Ōtautahi Christchurch.

Rākaihautū was the captain of the Uruaokapuarangi canoe and a Polynesian ancestor of various iwi, most famously of Waitaha and other southern groups, though he is also known in the traditions of Taitokerau and in those of Rarotonga.

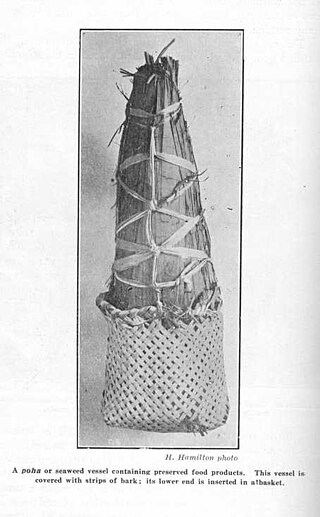

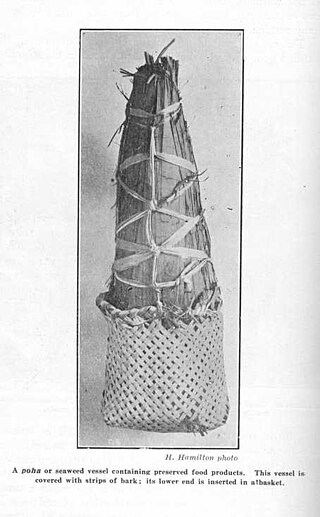

Pōhā are traditional bags used by the Māori people of New Zealand made from southern bull kelp, which are used to carry and store food and fresh water, to propagate live shellfish, and to make clothing and equipment for sports. Pōhā are especially associated with Ngāi Tahu, who have legally recognised rights for harvesting source species of kelp.

Coopers Lagoon / Muriwai is a small coastal waituna-type lagoon in the Canterbury region of New Zealand, located approximately halfway between the mouth of the Rakaia River and the outlet of the much larger Lake Ellesmere / Te Waihora. While the present-day lagoon is separated from the nearby Canterbury Bight by approximately 100 metres (330 ft), the water of the lagoon is considered brackish and early survey maps show that, until recently, the lagoon was connected to the ocean by a small channel. The lagoon, along with the surrounding wetlands, has historically been an important mahinga kai for local Māori.

Motukarara is a locality to the northeast of Lake Ellesmere / Te Waihora in the Selwyn District of New Zealand. State Highway 75 passes through the centre of the village, connecting Christchurch with Akaroa and the Banks Peninsula. The Little River Branch, which operated between 1886 and 1962, ran through Motukarara, and is now a shared walkway and cycleway.

The Tapuae-o-Uenuku / Hector Mountains are a mountain range in the New Zealand region of Otago, near the resort town of Queenstown and just south of the more famous Remarkables. For most of its length, the mountains run adjacent to the southern reaches of Lake Wakatipu, before extending approximately 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) further south, past the glacial moraine at Kingston on the southern end of the lake. On their eastern side, the mountains mark the edge of the Nevis valley, a largely tussocked area which saw significant activity during the Otago gold rush of the 1860s. Historically, the mountains were an important mahinga kai for Ngāi Tahu and other local Māori iwi, who used the area to hunt for weka and gather tikumu while visiting the region.

A waituna is a freshwater coastal lagoon on a mixed sand and gravel (MSG) beach, formed where a braided river meets a coastline affected by longshore drift. This type of waterbody is neither a true lake, lagoon nor estuary.

The Kaituna River is a small watercourse which drains the high ground on the Banks Peninsula before discharging into Lake Ellesmere / Te Waihora. It gives its name to a steep sheep-grazed valley which provides access to the walking tracks and mountain tops of Mount Bradley and Mount Herbert / Te Ahu Pātiki.

The Yarrs Flat Wildlife Reserve, also known as the Ararira Wetland, is a government purpose reserve on Lake Ellesmere / Te Waihora in Canterbury, New Zealand. It is jointly managed by the New Zealand Department of Conservation and the Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. During the 1980s, Yarrs Flat had some of the highest bird diversity in New Zealand, with seventy-five different species of birds observable in its 286 hectares (1.10 sq mi) area. As of the early twenty-first century, the flat provides a habitat for many native species of New Zealand, such as the Australasian bittern, curlew sandpiper, and red-necked stint. Today, it is an important nesting site for Australasian bitterns and is one of the few remaining areas of freshwater swamplands around Lake Ellesmere / Te Waihora.