Tolstoy, or Tolstoi, is a family of Russian gentry that acceded to the high aristocracy of the Russian Empire. The name Tolstoy is itself derived from the Russian adjective "толстый". They are the descendants of Andrey Kharitonovich Tolstoy, who moved from Chernigov to Moscow and served under Vasily II of Moscow in the 15th century. The "wild Tolstoys", as they were known in the high society of Imperial Russia, have left a lasting legacy in Russian politics, military history, literature, and fine arts.

The ten years 1917–1927 saw a radical transformation of the Russian Empire into a communist state, the Soviet Union. Soviet Russia covers 1917–1922 and Soviet Union covers the years 1922 to 1991. After the Russian Civil War (1917–1923), the Bolsheviks took control. They were dedicated to a version of Marxism developed by Vladimir Lenin. It promised the workers would rise, destroy capitalism, and create a socialist utopia under the leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The awkward problem was the small proletariat, in an overwhelmingly peasant society with limited industry and a very small middle class. Following the February Revolution in 1917 that deposed Nicholas II of Russia, a short-lived provisional government gave way to Bolsheviks in the October Revolution. The Bolshevik Party was renamed the Russian Communist Party (RCP).

The Tolstoyan movement is a social movement based on the philosophical and religious views of Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910). Tolstoy's views were formed by rigorous study of the ministry of Jesus, particularly the Sermon on the Mount.

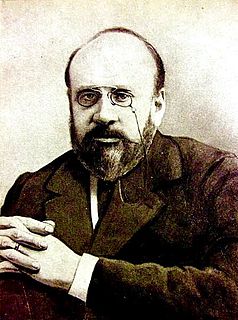

Vladimir Grigoryevich Chertkov (Russian: Влади́мир Григо́рьевич Чертко́в; also transliterated as Chertkoff, Tchertkoff, or Tschertkow was the editor of the works of Leo Tolstoy, and one of the most prominent Tolstoyans. After the revolutions of 1917, Chertkov was instrumental in creating the United Council of Religious Communities and Groups, which eventually came to administer the Russian SFSR's conscientious objection program.

Countess Alexandra (Sasha) Lvovna Tolstaya, often anglicized to Tolstoy, was the youngest daughter and secretary of the noted Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy.

Aylmer Maude and Louise Maude (1855–1939) were English translators of Leo Tolstoy's works, and Aylmer Maude also wrote his friend Tolstoy's biography, The Life of Tolstoy. After living many years in Russia the Maudes spent the rest of their life in England translating Tolstoy's writing and promoting public interest in his work. Aylmer Maude was also involved in a number of early 20th century progressive and idealistic causes.

Yasnaya Polyana is a writer's house museum, the former home of the writer Leo Tolstoy. It is 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) southwest of Tula, Russia, and 200 kilometres (120 mi) from Moscow.

Nikolai Fyodorovich Pogodin was a Soviet playwright. His plays were recognized in Soviet Union theater for their realistic portrayals of common life combined with socialist and communist themes. He is most widely known as the author of a trilogy about Lenin, the first time Lenin was used as a character in any theatrical works.

Russian anarchism is anarchism in Russia or among Russians. The three categories of Russian anarchism were anarcho-communism, anarcho-syndicalism and individualist anarchism. The ranks of all three were predominantly drawn from the intelligentsia and the working class, though the anarcho-communists – the most numerous group – made appeals to soldiers and peasants also.

The Last Station is a 2009 English-language German biographical drama film written and directed by Michael Hoffman, and based on Jay Parini's 1990 biographical novel of the same name, which chronicled the final months of Leo Tolstoy's life. The film stars Christopher Plummer as Tolstoy and Helen Mirren as his wife Sofya Tolstaya. The film is about the battle between Sofya and his disciple Vladimir Chertkov for his legacy and the copyright of his works. The film premiered at the 2009 Telluride Film Festival.

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, usually referred to in English as Leo Tolstoy, was a Russian writer who is regarded as one of the greatest authors of all time. He received nominations for the Nobel Prize in Literature every year from 1902 to 1906 and for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1901, 1902, and 1909. That he never won is a major controversy.

The Fruits of Enlightenment, aka Fruits of Culture is a play by the Russian writer Leo Tolstoy. It satirizes the persistence of unenlightened attitudes towards the peasants amongst the Russian landed aristocracy. In 1891 Constantin Stanislavski achieved success when he directed the play for his Society of Art and Literature organization.

The ideology of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) was Marxism–Leninism, an ideology of a centralised command economy with a vanguardist one-party state to realise the dictatorship of the proletariat. The Soviet Union's ideological commitment to achieving communism included the development of socialism in one country and peaceful coexistence with capitalist countries while engaging in anti-imperialism to defend the international proletariat, combat capitalism and promote the goals of communism. The state ideology of the Soviet Union—and thus Marxism–Leninism—derived and developed from the theories, policies and political praxis of Lenin and Stalin.

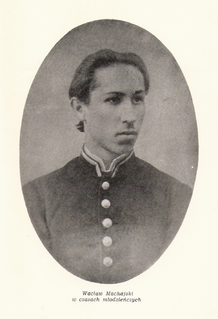

Jan Wacław Machajski, pseudonym A. Wolski, was a Polish revolutionary whose methodology drew from both anarchism and Marxism whilst criticising both as being products of the intelligentsia.

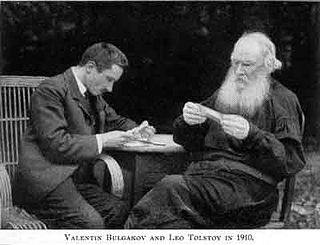

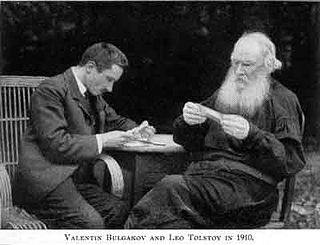

Valentin Fyodorovich Bulgakov was the last secretary of Leo Tolstoy and his biographer. He was director of a number of literary museums and was engaged in Tolstoyan, pacifist activities. He was imprisoned by the Tsarist regime and was a Nazi concentration camp survivor. During the final 20 years of his life he was head of the Yasnaya Polyana museum.

Arseny Borisovich Roginsky was a Soviet dissident and Russian historian. He was one of the founders of the International Historical and Civil Rights Society Memorial, its head since 1998.

Marxism and the National Question is a short work of Marxist theory written by Joseph Stalin in January 1913 while living in Vienna. First published as a pamphlet and frequently reprinted, the essay by the ethnic Georgian Stalin was regarded as a seminal contribution to Marxist analysis of the nature of nationality and helped to establish his reputation as an expert on the topic. Stalin would later become the first People's Commissar of Nationalities following the victory of the Bolshevik Party in the October Revolution of 1917.

The Last Station is a novel by Jay Parini that was first published in 1990. It is the story of the final year in the life of Leo Tolstoy, told from multiple viewpoints, including Tolstoy's young secretary, Valentin Bulgakov, his wife, Sophia Tolstaya, his daughter Sasha, his publisher and close friend, Vladimir Chertkov, and his doctor, Dushan Makovitsky. The novel was an international best-seller, translated into more than thirty languages, and adapted into an Academy Award-nominated film of the same name.

The Yasnaya Polyana Literary Award is an annual all-Russian literary award that was founded in 2003 by the Leo Tolstoy Museum Estate and Samsung Electronics. The award is presented for the best traditional-style novel written in Russian or translated into Russian.

Count Sergei Lvovich Tolstoy was a composer and ethnomusicologist who was among the first Europeans to make an in-depth study of the music of India. He was also an associate of the Sufi mystic, Inayat Khan, and participated in helping the Doukhobors move to Canada.