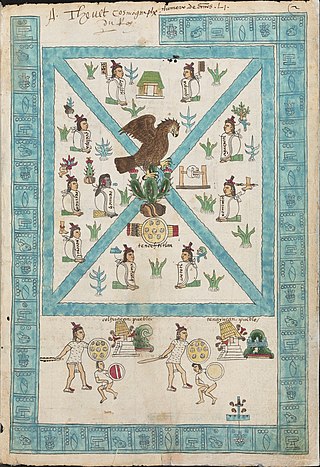

The Mapa Quinatzin is a 16th-century Nahua pictorial document, consisting of three sheets of amatl paper that depict the history of Acolhuacan.

The Mapa Quinatzin is a 16th-century Nahua pictorial document, consisting of three sheets of amatl paper that depict the history of Acolhuacan.

The codex was the historical ancestor of the modern book. Instead of being composed of sheets of paper, it used sheets of vellum, papyrus, or other materials. The term codex is often used for ancient manuscript books, with handwritten contents. A codex, much like the modern book, is bound by stacking the pages and securing one set of edges by a variety of methods over the centuries, yet in a form analogous to modern bookbinding. Modern books are divided into paperback and those bound with stiff boards, called hardbacks. Elaborate historical bindings are called treasure bindings. At least in the Western world, the main alternative to the paged codex format for a long document was the continuous scroll, which was the dominant form of document in the ancient world. Some codices are continuously folded like a concertina, in particular the Maya codices and Aztec codices, which are actually long sheets of paper or animal skin folded into pages.

The Nag Hammadi library is a collection of early Christian and Gnostic texts discovered near the Upper Egyptian town of Nag Hammadi in 1945.

The Madrid Codex is one of three surviving pre-Columbian Maya books dating to the Postclassic period of Mesoamerican chronology. A fourth codex, named the Grolier Codex, was discovered in 1965. The Madrid Codex is held by the Museo de América in Madrid and is considered to be the most important piece in its collection. However, the original is not on display due to its fragility; an accurate reproduction is displayed in its stead. At one point in time the codex was split into two pieces, given the names "Codex Troano" and "Codex Cortesianus". In the 1880s, Leon de Rosny, an ethnologist, realised that the two pieces belonged together, and helped combine them into a single text. This text was subsequently brought to Madrid, and given the name "Madrid Codex", which remains its most common name today.

Maya codices are folding books written by the pre-Columbian Maya civilization in Maya hieroglyphic script on Mesoamerican bark paper. The folding books are the products of professional scribes working under the patronage of deities such as the Tonsured Maize God and the Howler Monkey Gods. Most of the codices were destroyed by conquistadors and Catholic priests in the 16th century. The codices have been named for the cities where they eventually settled. The Dresden codex is generally considered the most important of the few that survive.

A codex, in the Warhammer 40,000 tabletop wargame, is a rules supplement containing information concerning a particular army, environment, or worldwide campaign.

The Dresden Codex is a Maya book, which was believed to be the oldest surviving book written in the Americas, dating to the 11th or 12th century. However, in September 2018 it was proven that the Maya Codex of Mexico, previously known as the Grolier Codex, is, in fact, older by about a century. The codex was rediscovered in the city of Dresden, Germany, hence the book's present name. It is located in the museum of the Saxon State Library. The codex contains information relating to astronomical and astrological tables, religious references, seasons of the earth, and illness and medicine. It also includes information about conjunctions of planets and moons.

The Paris Codex is one of four surviving generally accepted pre-Columbian Maya books dating to the Postclassic Period of Mesoamerican chronology. The document is very poorly preserved and has suffered considerable damage to the page edges, resulting in the loss of some of the text. The codex largely relates to a cycle of thirteen 20-year kʼatuns and includes details of Maya astronomical signs.

José Fernando Ramírez was a distinguished Mexican historian in the 19th century. He was a mentor of Alfredo Chavero, who considered him "the foremost of our historians."

Aztec codices are Mesoamerican manuscripts made by the pre-Columbian Aztec, and their Nahuatl-speaking descendants during the colonial period in Mexico.

Codex Ríos is an Italian translation and augmentation of a Spanish colonial-era manuscript, Codex Telleriano-Remensis, that is partially attributed to Pedro de los Ríos, a Dominican friar working in Oaxaca and Puebla between 1547 and 1562. The codex itself was likely written and drawn in Italy after 1566.

The traditions of indigenous Mesoamerican literature extend back to the oldest-attested forms of early writing in the Mesoamerican region, which date from around the mid-1st millennium BCE. Many of the pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica are known to have been literate societies, who produced a number of Mesoamerican writing systems of varying degrees of complexity and completeness. Mesoamerican writing systems arose independently from other writing systems in the world, and their development represents one of the very few such origins in the history of writing.

Mixtec writing originated as a logographic writing system during the Post-Classic period in Mesoamerican history. Records of genealogy, historic events, and myths are found in the pre-Columbian Mixtec codices. The arrival of Europeans in 1520 AD caused changes in form, style, and the function of the Mixtec writings. Today these codices and other Mixtec writings are used as a source of ethnographic, linguistic, and historical information for scholars, and help to preserve the identity of the Mixtec people as migration and globalization introduce new cultural influences.

In art history a speech scroll is an illustrative device denoting speech, song, or other types of sound.

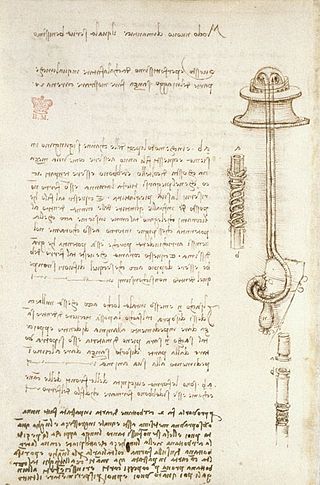

Codex Arundel, is a bound collection of pages of notes written by Leonardo da Vinci and dating mostly from between 1480 and 1518. The codex contains a number of treatises on a variety of subjects, including mechanics and geometry. The name of the codex came from the Earl of Arundel, who acquired it in Spain in the 1630s. It forms part of the British Library Arundel Manuscripts.

Nag Hammadi Codex XIII is a papyrus codex with a collection of early Christian Gnostic texts in Coptic. The manuscript is dated to the 4th century.

The Maya Codex of Mexico (MCM) is a Maya screenfold codex manuscript of a pre-Columbian type. Long known as the Grolier Codex or Sáenz Codex, in 2018 it was officially renamed the Códice Maya de México (CMM) by the National Institute of Anthropology and History of Mexico. It is one of only four known extant Maya codices, and the only one that still resides in the Americas.

The Madrid Codices I–II, are two manuscripts by Leonardo da Vinci which were discovered in the Biblioteca Nacional de España in Madrid in 1965 by Dr. Jules Piccus, Language Professor at the University of Massachusetts. The Madrid Codices I was finished during 1490 and 1499, and II from 1503 to 1505.

Quinatzin was a King of ancient Texcoco, an Acolhua city-state in Mexico. He was the first known ruler of that city and is also known as Quinatzin II.

Mesoamerican codices are manuscripts that present traits of the Mesoamerican indigenous pictoric tradition, either in content, style, or in regards to their symbolic conventions. The unambiguous presence of Mesoamerican writing systems in some of these documents is also an important, but not defining, characteristic, for Mesoamerican codices can comprise pure pictorials, native cartographies with no traces of glyphs on them, or colonial alphabetic texts with indigenous illustrations. Perhaps the best-known examples among such documents are Aztec codices, Maya codices, and Mixtec codices, but other cultures such as the Tlaxcaltec, the Purépecha, the Otomi, the Zapotecs, and the Cuicatecs, are creators of equally relevant manuscripts.