Related Research Articles

Concepts are defined as abstract ideas. They are understood to be the fundamental building blocks underlying principles, thoughts and beliefs. They play an important role in all aspects of cognition. As such, concepts are studied by several disciplines, such as linguistics, psychology, and philosophy, and these disciplines are interested in the logical and psychological structure of concepts, and how they are put together to form thoughts and sentences. The study of concepts has served as an important flagship of an emerging interdisciplinary approach called cognitive science.

Internalism and externalism are two opposite ways of integration of explaining various subjects in several areas of philosophy. These include human motivation, knowledge, justification, meaning, and truth. The distinction arises in many areas of debate with similar but distinct meanings. Internal–external distinction is a distinction used in philosophy to divide an ontology into two parts: an internal part concerning observation related to philosophy, and an external part concerning question related to philosophy.

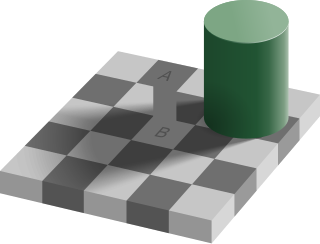

The philosophy of perception is concerned with the nature of perceptual experience and the status of perceptual data, in particular how they relate to beliefs about, or knowledge of, the world. Any explicit account of perception requires a commitment to one of a variety of ontological or metaphysical views. Philosophers distinguish internalist accounts, which assume that perceptions of objects, and knowledge or beliefs about them, are aspects of an individual's mind, and externalist accounts, which state that they constitute real aspects of the world external to the individual. The position of naïve realism—the 'everyday' impression of physical objects constituting what is perceived—is to some extent contradicted by the occurrence of perceptual illusions and hallucinations and the relativity of perceptual experience as well as certain insights in science. Realist conceptions include phenomenalism and direct and indirect realism. Anti-realist conceptions include idealism and skepticism. Recent philosophical work have expanded on the philosophical features of perception by going beyond the single paradigm of vision.

The problem of other minds is a philosophical problem traditionally stated as the following epistemological question: Given that I can only observe the behavior of others, how can I know that others have minds? The problem is that knowledge of other minds is always indirect. The problem of other minds does not negatively impact social interactions due to people having a "theory of mind" - the ability to spontaneously infer the mental states of others - supported by innate mirror neurons, a theory of mind mechanism, or a tacit theory. There has also been an increase in evidence that behavior results from cognition which in turn requires consciousness and the brain.

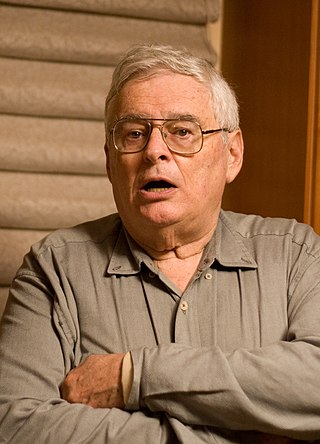

Hilary Whitehall Putnam was an American philosopher, mathematician, and computer scientist, and a major figure in analytic philosophy in the second half of the 20th century. He made significant contributions to philosophy of mind, philosophy of language, philosophy of mathematics, and philosophy of science. Outside philosophy, Putnam contributed to mathematics and computer science. Together with Martin Davis he developed the Davis–Putnam algorithm for the Boolean satisfiability problem and he helped demonstrate the unsolvability of Hilbert's tenth problem.

Solipsism is the philosophical idea that only one's mind is sure to exist. As an epistemological position, solipsism holds that knowledge of anything outside one's own mind is unsure; the external world and other minds cannot be known and might not exist outside the mind.

In philosophy of mind, functionalism is the thesis that each and every mental state is constituted solely by its functional role, which means its causal relation to other mental states, sensory inputs, and behavioral outputs. Functionalism developed largely as an alternative to the identity theory of mind and behaviorism.

Philosophy of psychology is concerned with the philosophical foundations of the study of psychology. It deals with both epistemological and ontological issues and shares interests with other fields, including philosophy of mind and theoretical psychology. Philosophical and theoretical psychology are intimately tied and are therefore sometimes used interchangeably or used together. However, philosophy of psychology relies more on debates general to philosophy and on philosophical methods, whereas theoretical psychology draws on multiple areas.

Eliminative materialism is a materialist position in the philosophy of mind. It is the idea that the majority of mental states in folk psychology do not exist. Some supporters of eliminativism argue that no coherent neural basis will be found for many everyday psychological concepts such as belief or desire, since they are poorly defined. The argument is that psychological concepts of behaviour and experience should be judged by how well they reduce to the biological level. Other versions entail the non-existence of conscious mental states such as pain and visual perceptions.

Jerry Alan Fodor was an American philosopher and the author of many crucial works in the fields of philosophy of mind and cognitive science. His writings in these fields laid the groundwork for the modularity of mind and the language of thought hypotheses, and he is recognized as having had "an enormous influence on virtually every portion of the philosophy of mind literature since 1960." At the time of his death in 2017, he held the position of State of New Jersey Professor of Philosophy, Emeritus, at Rutgers University, and had taught previously at the City University of New York Graduate Center and MIT.

Modularity of mind is the notion that a mind may, at least in part, be composed of innate neural structures or mental modules which have distinct, established, and evolutionarily developed functions. However, different definitions of "module" have been proposed by different authors. According to Jerry Fodor, the author of Modularity of Mind, a system can be considered 'modular' if its functions are made of multiple dimensions or units to some degree. One example of modularity in the mind is binding. When one perceives an object, they take in not only the features of an object, but the integrated features that can operate in sync or independently that create a whole. Instead of just seeing red, round, plastic, and moving, the subject may experience a rolling red ball. Binding may suggest that the mind is modular because it takes multiple cognitive processes to perceive one thing.

In philosophy, psychology, sociology, and anthropology, intersubjectivity is the relation or intersection between people's cognitive perspectives.

Neurophilosophy or philosophy of neuroscience is the interdisciplinary study of neuroscience and philosophy that explores the relevance of neuroscientific studies to the arguments traditionally categorized as philosophy of mind. The philosophy of neuroscience attempts to clarify neuroscientific methods and results using the conceptual rigor and methods of philosophy of science.

Semantic holism is a theory in the philosophy of language to the effect that a certain part of language, be it a term or a complete sentence, can only be understood through its relations to a larger segment of language. There is substantial controversy, however, as to exactly what the larger segment of language in question consists of. In recent years, the debate surrounding semantic holism, which is one among the many forms of holism that are debated and discussed in contemporary philosophy, has tended to centre on the view that the "whole" in question consists of an entire language.

Multiple realizability, in the philosophy of mind, is the thesis that the same mental property, state, or event can be implemented by different physical properties, states, or events. Philosophers of mind have used multiple realizability to argue that mental states are not the same as — and cannot be reduced to — physical states. They have also used it to defend many versions of functionalism, especially machine-state functionalism. In recent years, however, multiple realizability has been used to attack functionalism, the theory that it was originally used to defend. As a result, functionalism has fallen out of favor in the philosophy of mind.

In philosophy of mind, the computational theory of mind (CTM), also known as computationalism, is a family of views that hold that the human mind is an information processing system and that cognition and consciousness together are a form of computation. Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts (1943) were the first to suggest that neural activity is computational. They argued that neural computations explain cognition. The theory was proposed in its modern form by Hilary Putnam in 1967, and developed by his PhD student, philosopher, and cognitive scientist Jerry Fodor in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Despite being vigorously disputed in analytic philosophy in the 1990s due to work by Putnam himself, John Searle, and others, the view is common in modern cognitive psychology and is presumed by many theorists of evolutionary psychology. In the 2000s and 2010s the view has resurfaced in analytic philosophy.

Tyler Burge is an American philosopher who is a Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at UCLA. Burge has made contributions to many areas of philosophy, including the philosophy of mind, philosophy of logic, epistemology, philosophy of language, and the history of philosophy.

In metaphysics, metaphysical solipsism is the variety of idealism which asserts that nothing exists externally to this one mind, and since this mind is the whole of reality then the "external world" was never anything more than an idea. It can also be expressed by the assertion "there is nothing external to these present experiences", in other words, no reality exists beyond whatever is presently being sensed. The aforementioned definition of solipsism entails the non-existence of anything presently unperceived including the external world, causation, other minds, the past or future, and a subject of experience. Despite their ontological non-existence, these entities may nonetheless be said to "exist" as useful descriptions of the various experiences and thoughts that constitute 'this' mind.

Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that studies the ontology and nature of the mind and its relationship with the body. The mind–body problem is a paradigmatic issue in philosophy of mind, although a number of other issues are addressed, such as the hard problem of consciousness and the nature of particular mental states. Aspects of the mind that are studied include mental events, mental functions, mental properties, consciousness and its neural correlates, the ontology of the mind, the nature of cognition and of thought, and the relationship of the mind to the body.

Epistemology or theory of knowledge is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature and scope (limitations) of knowledge. It addresses the questions "What is knowledge?", "How is knowledge acquired?", "What do people know?", "How do we know what we know?", and "Why do we know what we know?". Much of the debate in this field has focused on analyzing the nature of knowledge and how it relates to similar notions such as truth, belief, and justification. It also deals with the means of production of knowledge, as well as skepticism about different knowledge claims.

References

- Fodor, Jerry (1980), “Methodological Solipsism Considered as a Research Strategy in Cognitive Psychology,” Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3: 63-73.

- Heath, Joseph (2005), "Methodological Individualism", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Eprint.

- McClamrock, Ron (1991), "Methodological Individualism Considered as a Constitutive Principle of Scientific Inquiry", Philosophical Psychology.

- Wood, Ledger (1962), "Solipsism", p. 295 in Runes (ed.), Dictionary of Philosophy, Littlefield, Adams, and Company, Totowa, NJ.