Minoan may refer to the following:

- Minoan, having to do with King Minos

- Minoan civilization

- Minoan, the script known as Linear A

- the (undeciphered) Minoan language written in that script

- the Eteocretan language, probably a descendant thereof

- the (undeciphered) Minoan language written in that script

- Minoan pottery

- Minoan eruption

- Minoan chronology

- Minoan seal-stones

- Minoan religion

- Minoan Modi, a peak sanctuary in eastern Crete

- Minoan Bull-leaper, a bronze in the British Museum

The Minoan language is the language of the ancient Minoan civilization of Crete written in the Cretan hieroglyphs and later in the Linear A syllabary. As the Cretan hieroglyphs are undeciphered and Linear A only partly deciphered, the Minoan language is unknown and unclassified: indeed, with the existing evidence, it seems impossible to be certain that the two scripts record the same language, or even that a single language is recorded in each. The Eteocretan language, attested in a few alphabetic inscriptions from Crete 1,000 years later, is possibly a descendant of Minoan, but it is itself unclassified.

Eteocretan is the non-Greek language of a few alphabetic inscriptions of ancient Crete.

Minoan pottery has been used as a tool for dating the mute Minoan civilization. Its restless sequence of quickly maturing artistic styles reveals something of Minoan patrons' pleasure in novelty while they assist archaeologists in assigning relative dates to the strata of their sites. Pots that contained oils and ointments, exported from 18th century BC Crete, have been found at sites through the Aegean islands and mainland Greece, on Cyprus, along coastal Syria and in Egypt, showing the wide trading contacts of the Minoans.

- Minoan, the script known as Linear A

- Cypro-Minoan syllabary, a script used on Cyprus

- Minoan, an old name for the Mycenean language before it was deciphered and discovered to be a form of Greek

- Minoan frescoes from Tell el-Daba, ancient Egyptian frescos in Minoan style

- Minoa, name of several bronze-age settlements in the Aegean.

- Minoan Group plc, a Glasgow-based travel and leisure company

- Minoan Lines, a Greek ferry company

- Minoan Air, a Greek airline

In Greek mythology, Minos was the first King of Crete, son of Zeus and Europa. Every nine years, he made King Aegeus pick seven young boys and seven young girls to be sent to Daedalus's creation, the labyrinth, to be eaten by the Minotaur. After his death, Minos became a judge of the dead in the underworld.

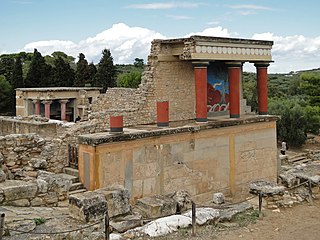

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age Aegean civilization on the island of Crete and other Aegean Islands which flourished from c. 2700 to c. 1450 BC, before a late period of decline, finally ending around 1100 BC. It represents the first advanced civilization in Europe, left behind massive building complexes, tools, stunning artwork, writing systems, and a massive network of trade. The civilization was rediscovered at the beginning of the 20th century through the work of British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans. The name "Minoan" derives from the mythical King Minos and was coined by Evans, who identified the site at Knossos with the labyrinth and the Minotaur. The Minoan civilization has been described as the earliest of its kind in Europe, and historian Will Durant called the Minoans "the first link in the European chain".

Linear A is a writing system used by the Minoans (Cretans) from 1800 to 1450 BC. Along with Cretan hieroglyphic, it is one of two undeciphered writing systems used by ancient Minoan and peripheral peoples. Linear A was the primary script used in palace and religious writings of the Minoan civilization. It was discovered by archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans. It is related to the Linear B script, which succeeded the Linear A and was used by the Mycenaean civilization.

| This disambiguation page lists articles associated with the title Minoan. If an internal link led you here, you may wish to change the link to point directly to the intended article. |