Related Research Articles

Consciousness, at its simplest, is sentience or awareness of internal and external existence. Despite millennia of analyses, definitions, explanations and debates by philosophers and scientists, consciousness remains puzzling and controversial, being "at once the most familiar and [also the] most mysterious aspect of our lives". Perhaps the only widely agreed notion about the topic is the intuition that consciousness exists. Opinions differ about what exactly needs to be studied and explained as consciousness. Sometimes, it is synonymous with the mind, and at other times, an aspect of mind. In the past, it was one's "inner life", the world of introspection, of private thought, imagination and volition. Today, it often includes any kind of cognition, experience, feeling or perception. It may be awareness, awareness of awareness, or self-awareness either continuously changing or not. There might be different levels or orders of consciousness, or different kinds of consciousness, or just one kind with different features. Other questions include whether only humans are conscious, all animals, or even the whole universe. The disparate range of research, notions and speculations raises doubts about whether the right questions are being asked.

Epiphenomenalism is a position on the mind–body problem which holds that physical and biochemical events within the human body are the sole cause of mental events. According to this view, subjective mental events are completely dependent for their existence on corresponding physical and biochemical events within the human body, yet themselves have no influence over physical events. The appearance that subjective mental states influence physical events is merely an illusion. For instance, fear seems to make the heart beat faster, but according to epiphenomenalism the biochemical secretions of the brain and nervous system —not the experience of fear—is what raises the heartbeat. Because mental events are a kind of overflow that cannot cause anything physical, yet have non-physical properties, epiphenomenalism is viewed as a form of property dualism.

The mind is the set of faculties responsible for mental phenomena. Often the term is also identified with the phenomena themselves. These faculties include thought, imagination, memory, will, and sensation. They are responsible for various mental phenomena, like perception, pain experience, belief, desire, intention, and emotion. Various overlapping classifications of mental phenomena have been proposed. Important distinctions group them together according to whether they are sensory, propositional, intentional, conscious, or occurrent. Minds were traditionally understood as substances but it is more common in the contemporary perspective to conceive them as properties or capacities possessed by humans and higher animals. Various competing definitions of the exact nature of the mind or mentality have been proposed. Epistemic definitions focus on the privileged epistemic access the subject has to these states. Consciousness-based approaches give primacy to the conscious mind and allow unconscious mental phenomena as part of the mind only to the extent that they stand in the right relation to the conscious mind. According to intentionality-based approaches, the power to refer to objects and to represent the world is the mark of the mental. For behaviorism, whether an entity has a mind only depends on how it behaves in response to external stimuli while functionalism defines mental states in terms of the causal roles they play. Central questions for the study of mind, like whether other entities besides humans have minds or how the relation between body and mind is to be conceived, are strongly influenced by the choice of one's definition.

In philosophy, physicalism is the metaphysical thesis that "everything is physical", that there is "nothing over and above" the physical, or that everything supervenes on the physical. Physicalism is a form of ontological monism—a "one substance" view of the nature of reality as opposed to a "two-substance" (dualism) or "many-substance" (pluralism) view. Both the definition of "physical" and the meaning of physicalism have been debated.

Free will is the capacity of agents to choose between different possible courses of action unimpeded.

In the philosophy of mind, mind–body dualism denotes either the view that mental phenomena are non-physical, or that the mind and body are distinct and separable. Thus, it encompasses a set of views about the relationship between mind and matter, as well as between subject and object, and is contrasted with other positions, such as physicalism and enactivism, in the mind–body problem.

In philosophy of mind, functionalism is the thesis that mental states are constituted solely by their functional role, which means, their causal relations with other mental states, sensory inputs and behavioral outputs. Functionalism developed largely as an alternative to the identity theory of mind and behaviorism.

Eliminative materialism is a materialist position in the philosophy of mind. It is the idea that the majority of the mental states in modern psychology do not exist. Some supporters of eliminativism argue that no coherent neural basis will be found for many everyday psychological concepts such as belief or desire, since they are poorly defined. Rather, they argue that psychological concepts of behaviour and experience should be judged by how well they reduce to the biological level. Other versions entail the non-existence of conscious mental states such as pain and visual perceptions.

The knowledge argument is a philosophical thought experiment proposed by Frank Jackson in his article "Epiphenomenal Qualia" (1982) and extended in "What Mary Didn't Know" (1986). The experiment describes Mary, a scientist who exists in a black and white world where she has extensive access to physical descriptions of color, but no actual human perceptual experience of color. The central question of the thought experiment is whether Mary will gain new knowledge when she goes outside the black and white world and experiences seeing in color.

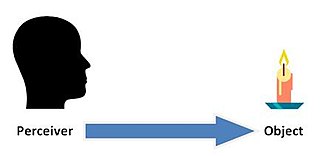

In the philosophy of perception and philosophy of mind, the question of direct or naïve realism, as opposed to indirect or representational realism, is the debate over the nature of conscious experience; out of the metaphysical question of whether the world we see around us is the real world itself or merely an internal perceptual copy of that world generated by our conscious experience.

The hard problem of consciousness is the problem of explaining why and how humans have qualia or phenomenal experiences. This is in contrast to the "easy problems" of explaining the physical systems that give us and other animals the ability to discriminate, integrate information, and so forth. These problems are seen as relatively easy because all that is required for their solution is to specify the mechanisms that perform such functions. Philosopher David Chalmers writes that even once we have solved all such problems about the brain and experience, the hard problem will still persist.

In philosophy, emergentism is the belief in emergence, particularly as it involves consciousness and the philosophy of mind. A property of a system is said to be emergent if it is a new outcome of some other properties of the system and their interaction, while it is itself different from them. Within the philosophy of science, emergentism is analyzed both as it contrasts with and parallels reductionism.

Herbert Feigl was an Austrian-American philosopher and an early member of the Vienna Circle. He coined the term "nomological danglers".

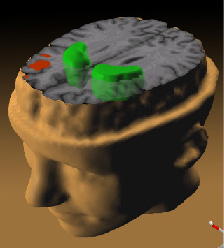

Type physicalism is a physicalist theory in the philosophy of mind. It asserts that mental events can be grouped into types, and can then be correlated with types of physical events in the brain. For example, one type of mental event, such as "mental pains" will, presumably, turn out to be describing one type of physical event.

Anomalous monism is a philosophical thesis about the mind–body relationship. It was first proposed by Donald Davidson in his 1970 paper "Mental Events". The theory is twofold and states that mental events are identical with physical events, and that the mental is anomalous, i.e. under their mental descriptions, relationships between these mental events are not describable by strict physical laws. Hence, Davidson proposes an identity theory of mind without the reductive bridge laws associated with the type-identity theory. Since the publication of his paper, Davidson has refined his thesis and both critics and supporters of anomalous monism have come up with their own characterizations of the thesis, many of which appear to differ from Davidson's.

Ullin Thomas Place, usually cited as U. T. Place, was a British philosopher and psychologist. Along with J. J. C. Smart, he developed the identity theory of mind. He taught for some years in the Department of Philosophy in the University of Leeds.

Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that studies the ontology and nature of the mind and its relationship with the body. The mind–body problem is a paradigmatic issue in philosophy of mind, although a number of other issues are addressed, such as the hard problem of consciousness and the nature of particular mental states. Aspects of the mind that are studied include mental events, mental functions, mental properties, consciousness and its neural correlates, the ontology of the mind, the nature of cognition and of thought, and the relationship of the mind to the body.

The mind–body problem is a debate concerning the relationship between thought and consciousness in the human mind, and the brain as part of the physical body. It is larger than, and goes beyond, just the question of how mind and body function chemically and physiologically, as that question presupposes an interactionist account of mind–body relations. This question arises when mind and body are considered as distinct, based on the premise that the mind and the body are fundamentally different in nature.

In philosophy of mind, qualia are defined as individual instances of subjective, conscious experience. The term qualia derives from the Latin neuter plural form (qualia) of the Latin adjective quālis meaning "of what sort" or "of what kind" in a specific instance, such as "what it is like to taste a specific apple — this particular apple now".

Interactionism or interactionist dualism is the theory in the philosophy of mind which holds that matter and mind are two distinct and independent substances that exert causal effects on one another. It is one type of dualism, traditionally a type of substance dualism though more recently also sometimes a form of property dualism.

References

- H. Feigl (1958), "The 'Mental' and the 'Physical'" in: Minnesota Studies in the Philosophy of Science II, pp. 370–497.

- J. J. C. Smart (1959), "Sensations and Brain Processes" in: Philosophical Review 68, pp. 141–156.